The Notification Apocalypse: Reclaiming Focus in 2025

TL;DR: Generation Z is the first cohort to come of age amid a polycrisis - interconnected global failures spanning climate, economy, democracy, and health. This cascading reality is fundamentally reshaping how young people think, plan their lives, and organize for change.

By 2030, most of Generation Z will have spent their entire adult lives navigating what researchers call a polycrisis - not just one disaster, but a web of interconnected catastrophes that amplify each other in ways humanity has never confronted before. Climate chaos triggers migration crises. Economic instability fuels democratic erosion. Pandemic fallout reshapes mental health landscapes. And unlike their parents who faced discrete challenges, today's youth are inheriting a world where these crises don't take turns - they compound.

The term "polycrisis" burst into mainstream discourse at the World Economic Forum's January 2023 Davos meeting, where Time magazine declared it the buzzword of the day. But behind the jargon lies a stark reality: Generation Z and younger Millennials are the first cohort to come of age fully immersed in this new normal of cascading global failures. And it's fundamentally changing how they think, live, and plan for a future that feels increasingly uncertain.

Polycrisis isn't just experiencing multiple crises at once - it's about how they interact. Think of it like a storm system: individual weather fronts might be manageable, but when they converge, they create something exponentially more destructive. That's what's happening globally, according to research published in Global Sustainability by Cambridge University Press.

The defining characteristic of polycrisis is interconnectedness. Climate disasters don't stay contained to environmental damage - they cascade into food insecurity, economic disruption, and mass displacement. Democratic backsliding doesn't happen in isolation - it interacts with social media echo chambers, economic anxiety, and eroding trust in institutions. Each crisis amplifies the others, creating feedback loops that traditional single-issue crisis management can't address.

Historian Adam Tooze, who popularized the term in policy circles, argues that polycrisis represents a fundamental shift in how we must understand global challenges. In his Chartbook analysis, he notes that we're moving beyond what he calls "Neoliberal Order Breakdown Syndrome" into territory where the very systems designed to manage risk are themselves becoming sources of instability.

Polycrisis isn't just multiple crises happening at once - it's about how they amplify each other through interconnected feedback loops that traditional crisis management can't address.

For young people, this isn't abstract theory - it's their daily reality. They're making life decisions in an environment where the basic assumptions previous generations relied on - steady economic growth, environmental stability, functional democracy - no longer hold.

To understand the polycrisis generation's worldview, trace the timeline of their formative years. Today's 25-year-olds were 16 when Donald Trump's election signaled a global wave of populist disruption to democratic norms. They were 18 during the wave of youth climate strikes led by Greta Thunberg. They spent their late teens and early twenties navigating the COVID-19 pandemic, which killed over seven million people globally and disrupted education, socialization, and career entry during critical developmental years.

The pandemic exposed the interconnected nature of global systems in visceral ways. Supply chains collapsed. Healthcare systems buckled. Economic inequality widened dramatically. The crisis revealed how fragile the infrastructure of modern life actually was - and that vulnerability hasn't been fixed, it's been normalized.

Then came the economic reckoning. Inflation surged to levels not seen in four decades. Housing prices soared beyond the reach of young first-time buyers. Student loan debt reached $1.77 trillion in the United States alone, with the average borrower owing over $37,000. Meanwhile, wages stagnated and the traditional path to middle-class security - college degree, stable job, homeownership - became increasingly unattainable.

Climate disasters escalated from abstract future threats to present-day catastrophes. Wildfires consumed entire communities. Floods devastated major cities. Heat waves killed thousands. Each summer broke temperature records. For Gen Z, climate change isn't a political issue to debate - it's the background noise of their entire lives.

And through it all, democratic institutions showed strain. Polarization intensified. Misinformation proliferated. Trust in government, media, and expertise declined. Young people watched as the systems supposedly designed to solve these problems seemed incapable of even acknowledging their interconnected nature.

Perhaps nothing captures the polycrisis generation's experience more than the youth mental health crisis. But here's the uncomfortable truth: calling it a mental health crisis might miss the point. When anxiety becomes a rational response to objective threats, is it still a disorder?

Research published in Frontiers in Psychiatry documents unprecedented levels of depression, anxiety, and psychological distress among young people. Depression rates among Gen Z are higher than any previous generation. But as one researcher noted, "It's not that young people are irrational - it's that the world they're inheriting is genuinely more precarious."

"It's not that young people are irrational - it's that the world they're inheriting is genuinely more precarious."

— Youth mental health researcher

Climate anxiety represents a particularly complex phenomenon. A 2024 study found that Gen Z feels significantly more impacted by climate change than older generations, with many reporting feelings of hopelessness about the future. Three-quarters of young people in a GlobeScan survey reported feeling that climate change will significantly affect their personal future.

This isn't just about environmental concern - it's about life trajectory planning. Significant numbers of young people are questioning whether to have children, where to live, what careers to pursue, all through the lens of climate instability. One 28-year-old told Inside Climate News: "I can't plan five years ahead when I don't know if my city will be habitable."

The pandemic's impact on youth mental health compounded these existing anxieties. Research published in The Psychiatrist identified pandemic-era disruption as a critical accelerant of youth psychological distress, particularly affecting those in formative developmental stages. Social isolation during key years for identity formation and peer relationships created what some researchers call a "lost cohort" - young people who missed irreplaceable developmental experiences.

But labeling this purely as mental illness obscures an important distinction: much of what's being called anxiety or depression in young people is actually an appropriate emotional response to genuine, unprecedented threats. The Breaking Down Gen Z's Mental Health Crisis analysis argues that we need to separate clinical disorders from rational distress about objectively deteriorating conditions.

The polycrisis isn't just affecting how young people feel - it's fundamentally changing how they live. Traditional life milestones are being delayed, reconsidered, or abandoned entirely.

Homeownership, once the cornerstone of middle-class achievement, has become a fantasy for many young adults. Housing prices have far outpaced wage growth, with median home prices in major cities requiring income levels that few entry-level professionals can achieve. The result is a generation of permanent renters, unable to build equity or achieve the financial stability their parents took for granted.

Higher education has transformed from an investment in the future into a source of crushing debt. The student loan crisis has profound economic ripple effects: young people delay homebuying, delay having children, delay starting businesses, all because of debt service that consumes 20-30% of their income. And unlike previous generations, many question whether the degree was even worth it, as they find themselves underemployed in jobs that don't require their education.

Family planning decisions reflect the deepest anxieties about polycrisis. Birthrates among Millennials and Gen Z have dropped significantly, and while some of this reflects changing social norms, qualitative research reveals that climate concerns play a major role. Young people describe feeling it would be "unethical" or "selfish" to bring children into a world facing such severe challenges. This isn't just personal anxiety - it represents a fundamental questioning of generational continuity itself.

Young people aren't just delaying traditional milestones like homeownership and having children - they're fundamentally questioning whether these milestones make sense in a world facing cascading crises.

Career trajectories have shifted too. Rather than seeking traditional corporate ladder climbing, many young people prioritize flexibility, remote work options, and alignment with values. This isn't entitlement - it's adaptation to a world where company loyalty means little, pensions are extinct, and economic stability can evaporate overnight. The gig economy isn't just a side hustle, it's a rational response to the absence of stable, full-time employment opportunities.

Even geographic mobility patterns are changing. Young people are increasingly factoring climate projections into where they choose to live. Coastal cities face sea-level rise. Western regions battle worsening wildfires and water scarcity. The Urban Institute notes that living costs in climate-resilient areas are rising as migration patterns shift, creating new forms of inequality between those who can afford to move and those who can't.

Yet despite - or perhaps because of - these challenges, Gen Z has emerged as a powerful activist force. The polycrisis generation isn't just despairing; they're organizing.

Climate activism represents the most visible manifestation. The youth climate movement, catalyzed by figures like Greta Thunberg, has mobilized millions globally. Pew Research found that Millennials and Gen Z stand out significantly for climate activism and social media engagement with the issue compared to older generations. School strikes, direct action protests, and litigation against governments represent a generation refusing to accept inaction on existential threats.

What distinguishes this activism is its systemic perspective. Rather than treating climate change as a single issue, youth activists connect it to economic inequality, racial justice, and democratic participation. They inherently understand polycrisis even if they don't use the term - they see how the pieces connect.

Gen Z protests span far beyond climate. Black Lives Matter mobilizations following George Floyd's murder drew overwhelming youth participation. Movements for gun control after school shootings have been led primarily by teenagers and young adults. Democratic participation campaigns have achieved record youth voter turnout in recent elections. In each case, young activists frame their work in terms of systemic change rather than incremental reform.

Social media plays a complex role. Critics argue it amplifies anxiety and spreads misinformation. But it's also created unprecedented coordination capacity. The NAACP notes that Gen Z's challenge is transforming activism into lasting change - translating viral moments into institutional transformation. TikTok climate communities share information, organize actions, and build solidarity across borders. Instagram activism raises awareness rapidly. Online organizing bypasses traditional gatekeepers.

The tension between apathy narratives and reality reveals generational misunderstanding. Older commentators sometimes interpret youth disengagement from traditional political structures as apathy, when it actually reflects strategic reorientation toward direct action and mutual aid networks. Young people haven't given up - they've stopped believing that existing institutions will save them and are building alternatives.

One of polycrisis's most corrosive effects is widening intergenerational conflict. Climate activists frame it explicitly as intergenerational injustice - older generations created the crisis, younger generations bear the consequences.

This extends beyond climate. Housing policy favors existing homeowners over first-time buyers. Social security and healthcare spending skews toward older cohorts while youth services face cuts. Political power concentrates in older age brackets. The result is a growing perception among young people that they're being sacrificed to protect their elders' comfort.

"When elders urge patience and working within the system, youth hear 'wait your turn while the world burns.'"

— Analysis of intergenerational communication

Economic data supports this. Wealth accumulation among Millennials and Gen Z lags far behind where their parents and grandparents were at the same age. Real wages for young workers have stagnated while costs for essentials - housing, healthcare, education - have skyrocketed. The generational wealth transfer that previous cohorts benefited from is breaking down as more baby boomers face their own financial precarity.

But the divide runs deeper than economics. It's philosophical. Older generations grew up in an era of relative stability and assume institutions will ultimately function. Younger generations have only known dysfunction and approach systems with skepticism bordering on cynicism. When elders urge patience and working within the system, youth hear "wait your turn while the world burns."

UNICEF's work on climate change and youth engagement emphasizes that young people must be included in decision-making processes, not just as token representatives but as equal stakeholders. The current exclusion of youth voices from the spaces where polycrisis responses are being designed virtually guarantees those responses will fail to address the realities young people face.

Some promising intergenerational collaborations exist. Grandparents' climate movements support youth activists. Some policymakers actively recruit young advisors. But these remain exceptions. The dominant pattern is gerontocracy - rule by the old - while the polycrisis generation that will live longest with the consequences has minimal power to shape responses.

Understanding polycrisis requires examining its structural origins. Research published in Global Sustainability applies neo-Gramscian analysis to argue that polycrisis emerges from fundamental contradictions within global capitalism combined with increasing systemic complexity.

The neoliberal economic order that dominated the late 20th century prioritized efficiency through just-in-time supply chains, financialization, and globalized production. These systems generated enormous wealth but at the cost of resilience. When disruptions occur - a pandemic, a climate disaster, a geopolitical conflict - the lack of redundancy means localized shocks cascade globally.

Deregulation and privatization transferred risks from institutions to individuals. Social safety nets weakened just as economic precarity increased. The result is a generation bearing individual responsibility for systemic failures - student debt from defunded education, medical debt from inadequate healthcare, housing insecurity from commodified shelter.

Meanwhile, complexity itself became a source of vulnerability. Interdependent global systems created efficiency gains but also created pathways for contagion - financial, epidemiological, informational. A problem in one domain rapidly spreads to others through connections that are often invisible until they fail.

For young people, this means the polycrisis isn't just bad luck or poor leadership - it's baked into the economic and political systems they're inheriting. That recognition drives more radical demands for systemic transformation rather than incremental reform.

Academic analysis of polycrisis is rapidly expanding as researchers recognize the inadequacy of traditional single-issue frameworks. Annual Reviews' characterization of the global polycrisis synthesizes recent literature to identify key patterns and knowledge gaps.

One finding is that polycrisis events are becoming more frequent and severe. What used to be considered "once in a century" shocks now occur multiple times per decade. Climate attribution science confirms that extreme weather events are intensifying. Economic modeling shows financial systems are more fragile than pre-2008 assumptions suggested. Epidemiological research warns that pandemic risks are rising due to zoonotic disease spillover from ecological disruption.

Another key insight is that polycrisis disproportionately impacts the vulnerable. Within the youth cohort, marginalized groups - racial minorities, LGBTQ+ individuals, those with disabilities, lower-income families - experience cascading crises more severely. Climate disasters hit poor communities hardest. Economic downturns devastate those without wealth buffers. Pandemic disruptions affected students in underfunded schools more than affluent peers with private tutors and stable internet.

Polycrisis events that used to be "once in a century" shocks now occur multiple times per decade, and they disproportionately impact the most vulnerable communities.

The Co-SPACE international consortium researches child and adolescent mental health during global crises, documenting how polycrisis affects development. Their work reveals that repeated traumatic events during formative years can have long-term cognitive and emotional effects, particularly when young people lack stable support systems.

Assessing the current state of polycrisis and systemic risk research identifies a critical gap: most studies still focus on individual crisis domains with insufficient attention to interactions and cascades. Bridging this gap requires interdisciplinary collaboration and new analytical frameworks that can capture complexity without becoming paralyzed by it.

If young people are inheriting a world defined by polycrisis, education systems need to prepare them accordingly. Currently, most curricula maintain siloed subjects - science separate from economics separate from civics - when the defining challenges require integrated understanding.

Polycrisis literacy means learning to think systemically. Understanding how climate change drives migration, which strains political systems, which fuels populism, which undermines climate action, which worsens climate change. Tracing feedback loops. Identifying leverage points. Recognizing that solving polycrisis requires addressing multiple domains simultaneously.

It also means emotional and psychological preparation. Young people need tools to maintain hope and agency in the face of genuinely overwhelming challenges. Research suggests that climate concern can actually drive positive action when paired with clear pathways for engagement. The key is avoiding both toxic positivity that denies reality and paralyzing nihilism that abandons agency.

Practical skills matter too. As traditional career paths become less reliable, young people need entrepreneurial capabilities, technical literacy, and adaptability. But beyond individual resilience, polycrisis education should emphasize collective action, mutual aid, and community organizing - the skills required to build alternatives when institutions fail.

While mainstream institutions struggle to address polycrisis, young people are developing grassroots solutions. These initiatives may seem small, but they're laboratories for systemic alternatives.

Mutual aid networks emerged during the pandemic as young organizers delivered food, shared resources, and provided community care when government responses fell short. These networks didn't disappear when lockdowns ended - they evolved into ongoing support systems that address poverty, housing instability, and social isolation.

Climate adaptation projects led by youth combine practical action with consciousness-raising. Urban farming initiatives build food security while educating about agricultural systems. Renewable energy cooperatives provide clean power while modeling democratic ownership. Ecosystem restoration projects sequester carbon while creating green jobs and community connection.

Digital organizing tools developed by youth activists enable rapid mobilization. Decentralized coordination, encrypted communication, and viral content strategies bypass traditional media and institutional gatekeepers. While these tools can be misused, they also create unprecedented capacity for bottom-up organizing.

Alternative economic models attract youth interest. Cooperatives, time banks, solidarity economies, and gift networks offer structures beyond both corporate capitalism and state control. Cryptocurrency and blockchain technology - despite many legitimate criticisms - appeal to young people skeptical of traditional financial institutions.

These experiments shouldn't be romanticized. Most operate at small scale with limited resources. Many fail or remain marginal. But collectively, they represent a generation refusing to simply accept polycrisis as inevitable, instead prototyping alternatives that might scale if conditions shift.

The polycrisis tests whether our institutions can evolve fast enough to remain relevant. So far, the evidence is mixed.

Some governments have begun adopting more integrated approaches. Cross-ministerial climate cabinets coordinate policy across domains. Whole-of-government pandemic responses demonstrated capacity for rapid mobilization. But these remain exceptions, and many such initiatives faded as acute crisis phases passed.

International institutions face particular challenges. The UN, IMF, and World Bank were designed for a different era. Their governance structures reflect mid-20th century power distributions that young people and Global South nations increasingly reject as illegitimate. Efforts at reform move glacially while polycrisis accelerates.

Some scholars argue that polycrisis may actually create opportunities for institutional transformation. The conversation article "Polycrisis may be a buzzword" but it could help us tackle the world's woes notes that recognizing interconnection might finally motivate the integrated responses that have long been theoretically desirable but practically difficult to implement.

Others are less optimistic. Historian Adam Tooze discusses how democracy itself is strained by polycrisis, as voters demand quick solutions to complex problems while demagogues offer simple scapegoats. The very uncertainty and anxiety that polycrisis generates create fertile ground for authoritarianism.

For young people watching these institutional struggles, the question becomes existential: do you invest energy trying to reform systems that seem fundamentally inadequate, or do you build alternatives outside them?

While this analysis focuses heavily on Western youth experience, polycrisis manifests differently across regions, and young people in the Global South face even more severe challenges.

Climate impacts hit equatorial regions hardest, where many of the world's youngest populations live. African youth face desertification, water scarcity, and agricultural collapse while having contributed least to carbon emissions. Pacific Island youth watch their entire nations threatened by sea-level rise. South Asian youth endure fatal heat waves and flooding.

Economic precarity is more extreme in developing economies. Youth unemployment rates in parts of Africa and the Middle East exceed 30%. Access to education is disrupted by conflict, poverty, and now climate disasters. Healthcare systems are less resourced to handle pandemic shocks.

Political instability and conflict disproportionately affect youth in fragile states. Forced migration, often driven by polycrisis factors, means young people growing up in refugee camps or navigating dangerous journeys seeking asylum. They experience polycrisis not as abstract interconnection but as literal survival threat.

Yet Global South youth also demonstrate remarkable resilience and innovation. African youth are building renewable energy infrastructure, developing climate-adapted agriculture, and creating digital platforms for grassroots organizing. Latin American youth lead environmental defense movements despite facing violence from extractive industries. These experiences deserve recognition beyond Western-centric narratives.

Forecasting in an age of polycrisis is inherently uncertain, but several potential trajectories seem plausible based on current trends.

One scenario is continued deterioration. Climate impacts worsen, economic inequality deepens, democratic institutions erode further, and young people inherit an increasingly dystopian landscape. In this trajectory, the youth mental health crisis intensifies, birthrates plummet, and social cohesion fractures as people retreat into survivalism.

Another possibility is breakthrough. Polycrisis becomes so acute that it finally catalyzes the systemic transformations that incremental reform couldn't achieve. Youth activism reaches critical mass, older generations face mortality of their choices, and wholesale economic and political restructuring becomes unavoidable. This isn't inevitable - it requires both crisis and organized movements ready to channel it toward justice rather than authoritarianism.

A third scenario is fragmentation. Different regions and communities respond to polycrisis in divergent ways, some adopting sustainable equitable models while others descend into ecological collapse and conflict. Youth experience varies enormously based on geography, wealth, and governance, creating even wider gulfs between the secure and the precarious.

Most likely is some combination - pockets of transformation amid ongoing deterioration, punctuated by acute crises that create brief windows for change. For young people, this means developing both the resilience to endure ongoing instability and the readiness to act when opportunities for systemic change emerge.

Perhaps the deepest challenge facing the polycrisis generation is psychological: learning to build meaningful lives amid radical uncertainty. Previous generations could reasonably expect that the future would resemble the present, with gradual improvements. That assumption is gone.

This doesn't mean abandoning planning entirely. But it requires different relationship to the future - holding plans lightly, building adaptive capacity, finding meaning in process rather than outcomes. It means accepting that you might have to change careers multiple times, relocate due to climate impacts, navigate economic disruptions, and adjust life plans repeatedly.

Some find this liberating. Without fixed scripts, there's space for experimentation and the freedom to define success differently than previous generations. Others find it terrifying, craving stability that seems impossible. Most oscillate between these responses.

Building community becomes crucial. Individualistic approaches to polycrisis are doomed - the challenges are too large, too interconnected for solo solutions. Young people who thrive are those who build robust networks of mutual support, shared resources, and collective action. Interdependence isn't weakness in an age of polycrisis; it's survival.

Finding purpose matters too. Research consistently shows that people who engage in meaningful work toward collective goals maintain better mental health even in adverse conditions. For young people, this might mean climate activism, community organizing, mutual aid, or any of countless efforts to make things slightly less bad and slightly more just.

There's a cruel irony in the polycrisis generation's predicament. They didn't create these interconnected crises - they inherited them from decisions made before they were born. Yet they're the ones who will have to live with the consequences longest, and paradoxically, they're also the ones most equipped to understand and address polycrisis because they've never known anything else.

Where older generations see separate problems requiring separate solutions, young people intuitively grasp interconnection. Where establishment institutions counsel patience and incremental reform, youth activism demands urgent systemic change commensurate with the scale of the crisis. Where conventional wisdom assumes some return to stability, the polycrisis generation is learning to build resilience within ongoing disruption.

This generation didn't ask to inherit a world on fire, underwater, and economically hollowed out. But inherit it they have. The question now is whether the rest of society will support them in transforming that inheritance, or continue defending systems that created polycrisis in the first place.

What's certain is that young people are already adapting. They're building new forms of community, organizing across borders, questioning assumptions that failed their predecessors, and developing the capabilities required to navigate cascading crises. The institutions that survive will be those that learn from youth rather than dismissing them.

The polycrisis generation didn't choose their historical moment. But they're rising to meet it with a clarity born of necessity. The rest of us should be paying attention.

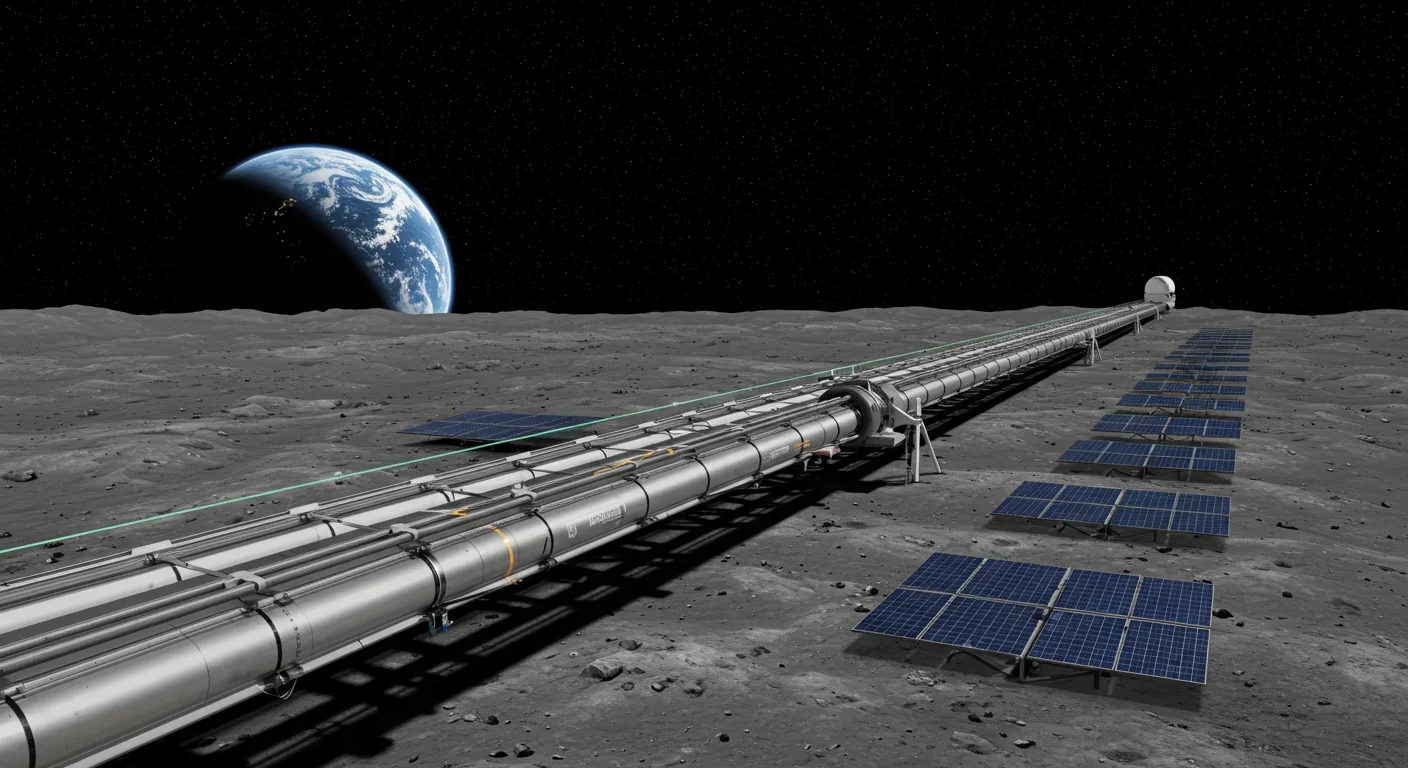

Lunar mass drivers—electromagnetic catapults that launch cargo from the Moon without fuel—could slash space transportation costs from thousands to under $100 per kilogram. This technology would enable affordable space construction, fuel depots, and deep space missions using lunar materials, potentially operational by the 2040s.

Ancient microorganisms called archaea inhabit your gut and perform unique metabolic functions that bacteria cannot, including methane production that enhances nutrient extraction. These primordial partners may influence longevity and offer new therapeutic targets.

CAES stores excess renewable energy by compressing air in underground caverns, then releases it through turbines during peak demand. New advanced adiabatic systems achieve 70%+ efficiency, making this decades-old technology suddenly competitive for long-duration grid storage.

Human children evolved to be raised by multiple caregivers—grandparents, siblings, and community members—not just two parents. Research shows alloparenting reduces parental burnout, improves child development, and is the biological norm across cultures.

Soft corals have weaponized their symbiotic algae to produce potent chemical defenses, creating compounds with revolutionary pharmaceutical potential while reshaping our understanding of marine ecosystems facing climate change.

Generation Z is the first cohort to come of age amid a polycrisis - interconnected global failures spanning climate, economy, democracy, and health. This cascading reality is fundamentally reshaping how young people think, plan their lives, and organize for change.

Zero-trust security eliminates implicit network trust by requiring continuous verification of every access request. Organizations are rapidly adopting this architecture to address cloud computing, remote work, and sophisticated threats that rendered perimeter defenses obsolete.