The Polycrisis Generation: Youth in Cascading Crises

TL;DR: Cities worldwide are empowering residents to shape neighborhoods through participatory planning—from participatory budgeting to community land trusts. This democratic shift produces more equitable, sustainable outcomes, though barriers like power resistance and capacity constraints remain.

By 2030, urban planners predict that more than half of all new neighborhood development projects in major cities will involve direct citizen participation in design decisions—a fundamental shift from the top-down planning that shaped cities for generations. What started as scattered grassroots experiments in participatory democracy has become a global movement transforming how we build the places we live. From Toronto's resident-operated housing cooperatives to London's community land trusts, citizens are no longer passive recipients of urban development—they're the architects of their own neighborhoods.

Traditional urban planning follows a familiar script: city officials and professional planners draft zoning maps and development proposals behind closed doors, hold a few perfunctory public hearings where residents voice objections that rarely change outcomes, then implement their vision regardless of community input. This top-down approach built the cities most of us inhabit today, with all their strengths and glaring inequities.

Participatory urban planning flips that script entirely. Instead of treating residents as obstacles to overcome or complaints to manage, it positions them as essential collaborators with deep knowledge of their neighborhoods' needs, challenges, and possibilities. The approach emerged from various social movements—participatory action research in Latin America during the 1970s, community development efforts in post-industrial American cities, and democratic experiments in European cooperative housing.

What makes this shift revolutionary isn't just the inclusion of more voices. It's the recognition that people who live in neighborhoods possess irreplaceable expertise about how those places actually function. They know which intersections feel dangerous at night, which parks teenagers avoid, where elderly residents struggle with accessibility, and which community spaces foster connection versus isolation. That granular, lived knowledge can't be replicated by planners studying census data and zoning maps from municipal offices.

Residents possess irreplaceable expertise about how neighborhoods actually function—knowledge that can't be replicated by planners studying data from municipal offices.

Cities worldwide have developed diverse methods for involving residents in planning decisions, ranging from shallow consultation to deep collaboration. The International Association for Public Participation identifies a spectrum of engagement: informing (one-way communication), consulting (gathering feedback), involving (working together on decisions), collaborating (partnering throughout), and empowering (placing final decision authority with communities).

Most traditional "public engagement" never moves beyond consulting—city officials present plans, residents comment, officials proceed largely unchanged. But meaningful participatory planning happens in the collaborate and empower zones, where community voices genuinely shape outcomes.

Participatory budgeting represents one of the most direct forms of citizen power. Originating in Porto Alegre, Brazil in 1989, this process allows residents to decide how to allocate portions of municipal budgets. Citizens attend assemblies, propose projects, debate priorities, and vote on spending. Since Brazil's pioneering efforts, participatory budgeting has spread to over 7,000 cities worldwide, from Paris to New York to Seoul. The amounts vary—some cities allocate a few million dollars, others dedicate substantial portions of their capital budgets—but the principle remains constant: those who live with the consequences should help determine the investments.

Design charrettes and co-design workshops bring residents, planners, architects, and city officials together for intensive collaborative sessions. Rather than presenting finished plans, professionals facilitate creative processes where community members sketch ideas, build models, and directly shape design directions. Bay State Cohousing in Malden, Massachusetts exemplifies this approach—up to 50 future residents gathered regularly for consensus decision-making workshops that guided every design detail, from the mint-green staircases to the shared courtyard layout.

Community mapping exercises help residents document neighborhood assets, problems, and aspirations that official data misses. Using paper maps, digital platforms like Maptionnaire, or mobile apps, people annotate their lived experiences onto geographic space: this corner needs better lighting, this lot could become a community garden, this building houses vulnerable residents who'd be displaced by redevelopment. These crowdsourced maps surface local knowledge that transforms abstract planning into situated problem-solving.

Community land trusts (CLTs) and housing cooperatives take participation beyond individual projects to ongoing neighborhood governance. In a CLT, a nonprofit organization holds land in trust for community benefit, leasing it to residents at rates tied to local median income rather than market values. Residents gain genuine ownership stakes while community boards—composed of residents, neighbors, and public representatives—maintain democratic oversight over development. Toronto's 60 Richmond Street East cooperative operates an 85-unit building where residents collectively govern, maintain edible gardens, and run their own restaurant.

Theoretical frameworks mean little without real-world results. Fortunately, two decades of participatory planning experiments have generated compelling evidence of what works.

Paris, France allocated €100 million annually for participatory budgeting from 2014-2020, allowing Parisians to propose and vote on projects. The city funded over 1,800 citizen-initiated projects, from urban gardens to public sports facilities to homeless services. Participation rates exceeded 200,000 voters in some years—not representative of all 2 million residents, but far broader engagement than traditional planning processes achieve. Research showed participatory budgeting increased civic trust, particularly among younger residents and immigrant communities previously disconnected from municipal governance.

Medellín, Colombia transformed from one of the world's most dangerous cities to an international model of inclusive urban development through participatory planning. Beginning in the early 2000s, the city invested heavily in previously marginalized hillside neighborhoods, but crucially involved residents in determining priorities. Communities helped design Metrocable gondola lines that connected isolated areas to the city center, Library Parks that became cultural anchors, and public escalators that reduced the physical isolation of steep neighborhoods. Resident participation didn't just improve the projects—it built community ownership that helped sustain improvements.

"On any given day, there'd be up to 50 people together in a room, keeping each other in check. The design process was guided by close collaboration with the clients."

— Jenny French, Architect, Bay State Cohousing

Portland, Oregon pioneered comprehensive neighborhood association systems that give residents formal roles in planning decisions. The city recognizes 95 neighborhood associations covering every part of Portland, with guaranteed opportunities to review and comment on land use decisions. While not perfect—associations sometimes reflect the demographics and priorities of older, whiter, wealthier residents rather than entire neighborhoods—the system creates structured channels for community influence that most American cities lack.

Citizens House in London demonstrates how even small-scale community-led projects can reshape neighborhoods. After 11 local residents formed a community land trust and spent years navigating planning obstacles, they developed 11 affordable homes with staggered balconies designed through collaborative workshops. The homes sell for 65% of market rate and remain permanently affordable through the trust structure. More importantly, the project inspired similar efforts across London and demonstrated that community-led development could work within existing legal frameworks.

Champlain Housing Trust in Burlington, Vermont operates the largest community land trust in the United States, managing over 2,200 homes and maintaining their affordability across generations. By separating land ownership (held by the trust) from building ownership (held by residents), the model keeps housing costs tied to local income levels rather than speculation. Residents participate in trust governance through elected boards, creating democratic accountability for neighborhood development decisions.

Traditional participatory planning required attending evening meetings at city hall—a significant barrier for working parents, shift workers, people with disabilities, or anyone without flexible schedules. Digital platforms are democratizing access to planning processes, though they create new challenges around digital divides.

Interactive mapping platforms like Maptionnaire and Commonplace allow residents to comment on proposals, identify problems, and suggest improvements on their own schedules via smartphones or computers. Cities from Helsinki to Boston use these tools to gather geographically specific feedback at scale—understanding not just that residents want better parks, but exactly which parks need specific improvements.

Virtual reality and 3D modeling help communities visualize proposed developments before construction begins. Architectural renderings and walkthroughs transform abstract blueprints into experiential previews that residents can meaningfully evaluate. Instead of interpreting floor plans and elevation drawings, community members can virtually walk through proposed buildings, assess sightlines, and identify design problems before they're built.

Online deliberation platforms enable structured conversations among hundreds or thousands of participants. Tools like Decidim (used by Barcelona) and Consul (used by Madrid) facilitate proposal submission, debate, amendment, and voting at scales impossible through in-person meetings. These platforms create transparency around decision-making processes while generating documented records of community input.

The challenge with digital participation tools is ensuring they expand rather than narrow democratic engagement. Research on participatory design shows that marginalized communities—elderly residents, low-income households, people with limited internet access—often remain underrepresented in digital processes. Effective participatory planning combines digital tools with traditional in-person engagement, translation services, childcare at meetings, and active outreach to ensure technology complements rather than replaces face-to-face community organizing.

Digital tools alone won't democratize planning. The fundamental question remains political: are cities willing to share power with residents?

Two decades of participatory planning experiments provide substantial evidence about outcomes—some expected, others surprising.

Community satisfaction increases significantly when residents genuinely influence decisions. Research on participatory budgeting shows participants report greater trust in local government, increased civic engagement, and stronger identification with their neighborhoods. This matters beyond feel-good measures—communities with higher social trust experience better health outcomes, lower crime, more effective collective problem-solving, and greater economic resilience.

Equity outcomes improve when marginalized communities gain voice. Traditional planning consistently produced inequitable results—highways through Black neighborhoods, industrial facilities near Latino communities, inadequate services in immigrant areas—because those with power made decisions affecting those without it. Participatory approaches create opportunities for historically excluded communities to advocate for their needs, though success depends on deliberate efforts to include marginalized voices rather than simply opening processes to whoever shows up.

Environmental sustainability benefits from local knowledge. Residents understand neighborhood-specific conditions that distant planners miss—where flooding occurs, which areas lack tree cover, how wind patterns affect pedestrian comfort, where wildlife corridors exist. Community-led urban greening initiatives often achieve better long-term maintenance and community use than top-down projects because residents have ownership stakes in their success.

Economic development becomes more responsive to actual needs. When communities help determine business district improvements, transit investments, or workforce development priorities, resources align more closely with local economic realities than when officials pursue generic development strategies. Community land trusts preserve affordability while conventional development displaces existing residents—a fundamental difference in who benefits from neighborhood improvements.

Project timelines often extend because meaningful participation takes time. Critics of participatory planning point to delayed projects and increased process complexity. But research suggests participatory approaches reduce later conflicts and opposition that often derail or delay conventionally planned projects. Time invested in front-end collaboration can prevent years of lawsuits, protests, and implementation obstacles.

If participatory planning produces better outcomes, why hasn't every city adopted it? Substantial obstacles limit where and how deeply cities embrace community-led approaches.

Power resistance represents the most fundamental barrier. Elected officials, appointed planning staff, and developers benefit from current decision-making structures that concentrate authority. Sharing that power means accepting constraints on their autonomy. Some opposition is principled—professionals may genuinely believe their expertise produces better outcomes than community input—but much reflects simple unwillingness to cede control.

Capacity constraints limit both government and community participation. Meaningful engagement requires staff time, facilitator expertise, meeting spaces, translation services, childcare, food, transit stipends, and other resources that cash-strapped municipalities struggle to provide. On the community side, effective participation demands time and energy that working families, people juggling multiple jobs, or residents managing health challenges often can't spare. Grassroots development requires sustained organizing, which demands resources marginalized communities typically lack.

Representation challenges plague even well-designed participatory processes. Who participates often doesn't reflect who lives in neighborhoods. Homeowners attend more than renters, long-time residents more than newcomers, older people more than younger, English speakers more than others. Without deliberate inclusion strategies—targeted outreach, translation, youth engagement, renter organizing—participatory processes can amplify rather than correct existing power imbalances.

"Community land trusts offer a formalized, scalable, community-led ownership and management structure that guarantees permanent affordability, with housing costs tied to median local income."

— French 2D / Azure Magazine

Technical complexity creates barriers when planning decisions require specialized knowledge. Residents may have strong views about neighborhood character but lack expertise in building codes, seismic safety, environmental regulations, infrastructure engineering, or development financing. Effective participatory planning requires translating technical information into accessible formats and creating spaces where professional expertise informs rather than dictates community decisions.

Scale limitations mean participatory approaches work more easily for neighborhood-scale decisions than regional systems. Individual communities can collaboratively design local parks, but regional transit networks, water systems, and housing markets require coordination across jurisdictions. Participatory planning risks devolving into NIMBY opposition when scaled up without mechanisms for addressing conflicts between local preferences and broader regional needs.

Legal and regulatory barriers obstruct community-led development even when residents want it. Zoning codes, building regulations, financing requirements, and liability rules were designed for conventional development, creating obstacles for cooperative housing, community land trusts, and other alternative models. Overcoming these barriers demands legal expertise and political capital many communities lack.

Participatory planning manifests differently across cultural contexts, reflecting distinct political traditions, property relations, and civic norms.

Latin American participatory budgeting emerged from social movements demanding democratization after authoritarian rule. Countries like Brazil, Uruguay, and Argentina embedded participatory budgeting into governance structures, with legal frameworks requiring citizen involvement. This institutionalization means participation persists across political changes rather than depending on individual mayors' commitments.

Nordic collaborative planning builds on social democratic traditions emphasizing consensus, welfare state provision, and social partnership. Swedish and Finnish cities integrate participation into comprehensive welfare planning, with extensive consultation around housing, transportation, and social services. The tradition produces high citizen trust but can default to professional-led processes with participation becoming performative rather than genuinely democratic.

Asian smart city participation often emphasizes technology-mediated engagement aligned with governance efficiency. Cities like Seoul, Singapore, and Shanghai deploy sophisticated digital platforms for citizen input on urban services, but participation typically remains consultative rather than empowering communities to make decisions. The approach generates useful feedback but maintains top-down authority structures.

African community-led development frequently operates outside formal planning systems in contexts where weak state capacity and rapid informal urbanization mean most residents already self-organize neighborhoods. Organizations like Slum Dwellers International support community-led upgrading where residents survey settlements, plan improvements, and negotiate with governments. This grassroots urbanism doesn't follow Western participatory planning models but achieves similar goals of community-directed development.

North American community organizing tradition emphasizes confrontational advocacy—residents organizing to oppose harmful projects or demand responsive services. This adversarial approach produced victories against urban highways and discriminatory housing policies, but creates tensions when cities attempt collaborative participatory processes. Decades of broken promises make many communities skeptical of participation that seems designed to legitimate predetermined decisions.

These different traditions suggest participatory planning isn't a single transferable model but diverse approaches shaped by local political cultures. What works in Porto Alegre won't necessarily work in Portland, and methods effective in Paris may fail in Nairobi. The core principles—respecting community knowledge, sharing decision-making power, ensuring inclusive participation—remain constant, but implementation must adapt to local contexts.

Understanding participatory planning matters little if you can't actually participate in shaping your own neighborhood. Here's how residents can engage, regardless of whether your city has formal participatory structures.

Start local and specific. Don't begin by trying to reform your entire city's planning process. Identify one issue affecting your immediate neighborhood—a dangerous intersection, deteriorating park, lacking transit service, affordable housing need. Build relationships with neighbors who share the concern. Small-scale organizing around concrete problems builds skills, relationships, and credibility for larger efforts.

Learn your city's existing participation channels. Most cities have community advisory boards, neighborhood councils, planning commission meetings, or other official engagement opportunities. These often have little power and low participation, but showing up consistently and bringing neighbors establishes your presence and reveals how decisions actually get made. Understanding existing processes helps identify where to apply pressure for more meaningful participation.

Document community knowledge systematically. Create your own neighborhood assessment—walk every street, photograph problems and assets, interview long-time residents, map where people gather and what they value. This grassroots research generates evidence that's hard for officials to dismiss and demonstrates your community's expertise about local conditions.

Build diverse coalitions beyond the usual suspects. Effective community organizing requires representation across differences—renters and homeowners, different age groups, various cultural communities, newcomers and long-timers. Knock on doors, host gatherings, meet people where they already gather. Wide participation strengthens your legitimacy and brings diverse perspectives that improve proposals.

Effective community organizing requires representation across differences—renters and homeowners, different age groups, various cultural communities, newcomers and long-timers.

Develop specific proposals, not just complaints. Officials can easily dismiss opposition but struggle to ignore concrete alternatives backed by community organizing. If you oppose a development, present an alternative. If you want better transit, propose specific route changes. Detailed proposals demonstrate seriousness and shift conversations from whether to address issues to how.

Connect with existing organizations doing participatory planning work. Community development corporations, affordable housing advocates, environmental justice groups, and urban planning reform organizations often need volunteers and provide training. National networks like the Institute for Local Self-Reliance or regional groups share resources and connect communities pursuing similar goals.

Use technology strategically but don't depend on it exclusively. Digital tools help organize, communicate, and document, but face-to-face relationships remain essential for sustained organizing. Start a neighborhood group chat or email list, but also host regular in-person gatherings. Use online mapping tools to crowdsource neighborhood knowledge, but also walk streets together.

Prepare for long timelines and setbacks. Meaningful participation doesn't happen quickly. The Citizens House project in London took years from initial organizing to completed homes. Zoning changes, funding applications, partnership building, and political advocacy all take time. Celebrate small victories, maintain relationships during quiet periods, and keep long-term vision alive through inevitable frustrations.

Study successful models and adapt them locally. Communities worldwide have pioneered participatory approaches you can learn from. Research how participatory budgeting works and consider proposing it for a small pot of funds in your city. Investigate community land trusts and whether that model could preserve affordability in your neighborhood. Adaptation beats invention—borrow proven strategies rather than starting from scratch.

The transformation of urban planning from expert-driven profession to collaborative community practice represents one of the most hopeful democratic experiments of our era. In a time of declining faith in institutions, participatory planning offers tangible proof that democratic decision-making can work at the scale of daily life.

But it's not inevitable. The barriers remain substantial, and many cities continue operating through top-down systems that marginalize community voices. The difference between cities where residents genuinely shape neighborhoods versus those where participation remains performative often comes down to sustained community organizing and political will.

The next decade will likely see continued expansion of participatory approaches, driven by several converging forces. Climate adaptation demands local knowledge about flood risks, heat islands, and resilience strategies that only residents possess. Housing affordability crises are generating grassroots organizing demanding community control over development. Digital tools continue lowering barriers to participation. Younger generations increasingly expect involvement in decisions affecting them.

Yet technology alone won't democratize planning. The fundamental question remains political: are cities willing to share power with residents, or will participation remain limited to consulting citizens about decisions officials have already made?

The evidence suggests empowering communities produces better outcomes—more equitable, more sustainable, more responsive to actual needs, more resilient through community ownership. What's required isn't more proof that participatory planning works, but more communities organizing to demand it and more officials willing to embrace genuinely democratic city-building.

The neighborhoods of 2040 could look fundamentally different depending on who shapes them. In one future, residents of all backgrounds participate in designing the places they live, creating neighborhoods that reflect diverse needs and aspirations. In another, planning remains the domain of professionals and developers, perpetuating the inequities and disconnections that characterize too many contemporary cities.

Which future emerges depends substantially on choices being made right now—in city halls where participation policies are debated, in neighborhoods where residents are organizing, in planning commissions where communities advocate for voice, and in the everyday decisions of people who choose to show up or stay home when their communities need them.

The tools exist. The models are proven. The question is whether enough people will use them to claim their right to shape the places where they live. Your neighborhood's future is being decided. The only question is whether you'll help decide it.

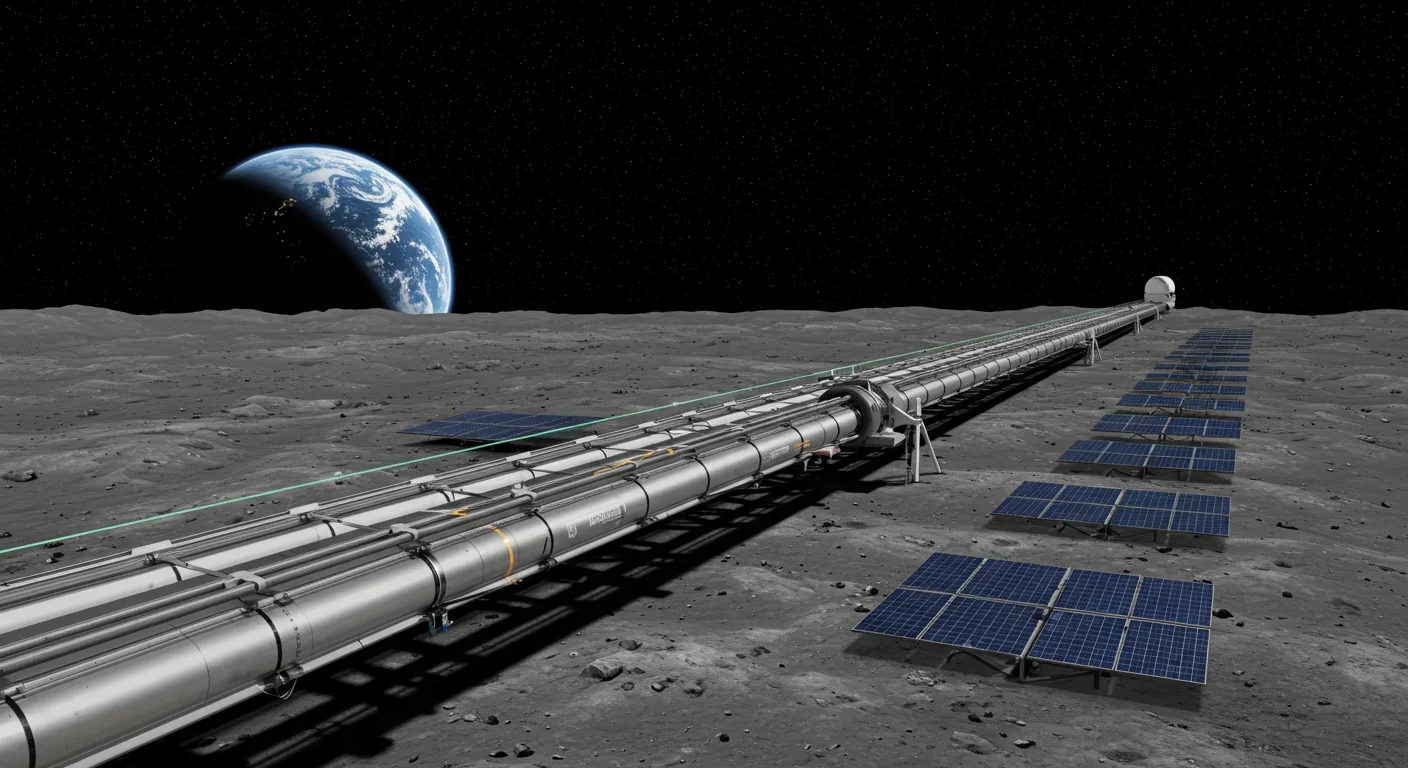

Lunar mass drivers—electromagnetic catapults that launch cargo from the Moon without fuel—could slash space transportation costs from thousands to under $100 per kilogram. This technology would enable affordable space construction, fuel depots, and deep space missions using lunar materials, potentially operational by the 2040s.

Ancient microorganisms called archaea inhabit your gut and perform unique metabolic functions that bacteria cannot, including methane production that enhances nutrient extraction. These primordial partners may influence longevity and offer new therapeutic targets.

CAES stores excess renewable energy by compressing air in underground caverns, then releases it through turbines during peak demand. New advanced adiabatic systems achieve 70%+ efficiency, making this decades-old technology suddenly competitive for long-duration grid storage.

Human children evolved to be raised by multiple caregivers—grandparents, siblings, and community members—not just two parents. Research shows alloparenting reduces parental burnout, improves child development, and is the biological norm across cultures.

Soft corals have weaponized their symbiotic algae to produce potent chemical defenses, creating compounds with revolutionary pharmaceutical potential while reshaping our understanding of marine ecosystems facing climate change.

Generation Z is the first cohort to come of age amid a polycrisis - interconnected global failures spanning climate, economy, democracy, and health. This cascading reality is fundamentally reshaping how young people think, plan their lives, and organize for change.

Zero-trust security eliminates implicit network trust by requiring continuous verification of every access request. Organizations are rapidly adopting this architecture to address cloud computing, remote work, and sophisticated threats that rendered perimeter defenses obsolete.