The Polycrisis Generation: Youth in Cascading Crises

TL;DR: Trust in institutions that define truth—media, science, government—has collapsed to historic lows, fracturing along partisan and generational lines. This erosion of epistemic authority, driven by polarization, digital misinformation, and institutional failures, now threatens public health, climate action, and democracy itself.

When Americans' trust in mass media dropped to 28% in 2025—the lowest in five decades of polling—it marked more than another bleak statistic. It signaled something deeper: a wholesale collapse of what researchers call "epistemic authority," the power of institutions to define what's true. From scientific bodies to government agencies, from universities to newsrooms, the institutions we once relied on to separate fact from fiction are hemorrhaging credibility. This isn't just about declining poll numbers. It's about the erosion of society's ability to agree on basic reality—and the consequences are already reshaping democracy, public health, and our collective future.

In 2018, the RAND Corporation published a landmark study that gave this phenomenon a name: Truth Decay. The researchers identified four distinct trends converging to undermine institutional authority. First, there's increasing disagreement about objective facts themselves—not just interpretations, but baseline reality. Second, there's a blurring of the line between opinion and fact in public discourse. Third, the sheer volume and relative influence of opinion over fact has exploded. Fourth, declining trust in formerly respected sources of factual information has become the new normal.

The report's findings were stark. Americans' reliance on facts to discuss public issues had declined significantly over two decades, leading to what RAND CEO Michael D. Rich called "political paralysis and collapse of civil discourse." The study traced how this erosion imposes real-world costs, pointing to the 2013 government shutdown that lasted 16 days and resulted in a $20 billion loss to the U.S. economy. But economic damage is just the start.

RAND's Truth Decay framework identifies four converging trends: increasing disagreement about objective facts, blurring of opinion and fact, the volume of opinion outweighing fact, and declining trust in factual sources.

RAND's framework helps us understand why this matters so much. When institutions lose their epistemic authority—their credibility to tell us what's known or true—we don't just get more arguments at Thanksgiving dinner. We get vaccine hesitancy during pandemics, climate inaction amid accelerating warming, and policy gridlock on issues demanding urgent collective action. Trust across "many more pillars of society—in government, media and financial institutions" has fallen to far lower absolute levels than before, creating a crisis that touches every aspect of civic life.

The numbers tell a sobering story. When Gallup began tracking Americans' views of news media in the early 1970s, attitudes were overwhelmingly positive, with 68-72% expressing confidence. By 1997, that had dropped to 53%. By 2024, just 31% trusted media to report news fully, accurately, and fairly. Today, only 28% of Americans express any trust in newspapers, television, and radio.

That steep decline dwarfs the erosion of trust in other institutions. When Gallup compared confidence across sectors in 2024, mass media ranked at the absolute bottom—below even Congress. Americans said they trusted their local governments (67%), state governments (55%), the judicial branch (48%), and the legislative branch (34%) more than they trusted news media. The Fourth Estate has become the least trusted pillar of democracy.

But it's not just media. Research published in the British Journal of Political Science analyzed over five million respondents from 50 survey projects spanning 1958 to 2019. Their conclusion: trust in representative institutions—parliaments, governments, political parties—has been declining worldwide since the 1960s. The trend is most pronounced in advanced democracies like the US, Canada, and UK, especially after 2016. In the United States, trust in the legislature fell from 41% to 32% between 2016 and 2019 alone, reaching a historical low.

Interestingly, the study found that trust in "implementing institutions"—civil service, courts, police—has remained relatively stable or even increased. This divergence matters. It suggests the crisis isn't about institutions broadly but specifically about those that set policy, shape narratives, and claim to speak for the public good. The very bodies meant to translate expertise into governance are the ones losing legitimacy.

If there's one pattern that leaps from the data, it's this: trust didn't decline evenly. It fractured along partisan and generational fault lines, transforming institutional credibility into a battleground of identity politics.

The partisan gap is staggering. In 2024, 54% of Democrats said they trusted media, compared with just 12% of Republicans. Among Republicans, 59% reported no trust at all in mass media—a view that surged 21 percentage points between 2015 and 2017, during the early Trump era. Political affiliation now predicts your relationship with institutional knowledge more powerfully than almost any other variable.

"Political trust is polarized along party lines: partisans tend to have almost no trust in the government run by the opposing party."

— Political Science Research on Polarization

This isn't an accident. Research shows that individual-level ideological polarization drives political engagement but simultaneously erodes trust in governmental institutions. The more extreme your ideological position becomes, the more politically active you are—and the less you trust public authorities. It's a paradox: higher civic participation paired with collapsing confidence in the very institutions democracy depends on.

The age divide compounds this. Americans aged 65 or older were more likely to express trust (43%) compared with those aged 18-29 (26%)—a 17-point gap. Younger generations, who've grown up with algorithmic feeds and influencer culture, are far less inclined to defer to legacy authorities. The implication is chilling: as older cohorts age out, baseline trust in institutions may decline further still.

What's driving this polarization of trust? One factor is elite messaging. When political leaders explicitly attack institutions as corrupt, biased, or captured by opponents, their supporters listen. President Trump's press secretary cited declining media trust as justification for reserving White House press briefings for "nontraditional new media" like podcasts, blogs, and social media. The message was clear: legacy media can't be trusted, so we're going around them.

Another driver is selective exposure. Media content has become ever more polarized, and people increasingly consume information that confirms their existing beliefs. Algorithms amplify this tendency, feeding us content that maximizes engagement—often the most emotionally charged, divisive material. The result is echo chambers where confirmation bias gets reinforced and institutional distrust accelerates.

If polarization fractured trust along ideological lines, the digital revolution democratized—and destabilized—the entire information ecosystem. The same technologies that promised to liberate knowledge from gatekeepers have created what the World Economic Forum identified in January 2024 as the most severe global risk in the short term: misinformation and disinformation propagated by both internal and external interests "to widen societal and political divides."

Social media platforms supercharge the spread of false information. A 2018 Twitter study found that compared to accurate information, false information spread significantly faster, further, deeper, and more broadly. Post-election surveys in 2016 suggested that many individuals who intake false information on social media believe it to be factual. During disasters, misleading messages often outpace official communications, resulting in reduced trust and exacerbating anxiety, stress, and fear.

The infodemic isn't just about volume, though. It's about what researchers call "information overload": the sheer glut of content makes it nearly impossible for individuals to discern credible sources from unreliable ones. When your uncle's Facebook post sits alongside a peer-reviewed study in your feed, each accompanied by confident assertions, traditional markers of expertise lose their power.

This dynamic directly challenges institutional authority. Why trust a scientist when a confident YouTuber with millions of followers says the opposite? Why defer to a journalist when your preferred influencer offers a more emotionally satisfying narrative? The digital age hasn't eliminated expertise; it's just multiplied the number of people claiming it.

The consequences are measurable. Consider vaccine hesitancy. While the scientific consensus that vaccines are safe and effective is overwhelming, myths, conspiracy theories, and misinformation spread by anti-vaccination movements have fueled public skepticism. By 2023, 36% of Americans believed the risks of COVID-19 vaccines outweighed their benefits—a stunning rejection of public health authority during a pandemic.

False information on social media spreads faster, further, deeper, and more broadly than accurate information—creating an environment where misinformation can outpace official communications during critical moments.

Or consider climate change. Despite 97% scientific consensus on human-caused warming, denial campaigns funded by fossil fuel interests have sown doubt for decades. These campaigns didn't need to win the scientific argument. They just needed to create enough confusion that policymakers and the public felt justified in delaying action. The strategy worked. As one analysis found, more than 90% of papers skeptical of climate change originate from right-wing think tanks—not from the scientific community.

The digital infodemic and political polarization didn't occur in a vacuum. They found fertile ground because institutions themselves handed critics the ammunition. A series of high-profile failures shattered the assumption that experts and authorities deserved automatic deference.

The Iraq War stands as Exhibit A. In 2003, U.S. and British governments assured the world that Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction, citing intelligence assessments as definitive proof. The media largely amplified rather than scrutinized these claims. When no WMDs materialized, the damage to institutional credibility was profound. If the government, intelligence agencies, and press could all be so catastrophically wrong about the pretext for war, what else might they be wrong about?

The 2008 financial crisis delivered another blow. Economists, regulators, and ratings agencies failed to foresee—or prevent—a collapse that wiped out trillions in wealth and threw millions out of work. The experts who'd assured everyone the system was sound were revealed as either incompetent or captured by the industries they were supposed to oversee. Trust in financial institutions plummeted and hasn't fully recovered.

More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic exposed deep tensions between scientific expertise and public trust. Early messaging on masks reversed. Predictions about the virus's trajectory proved overly optimistic. The lab-leak hypothesis, initially dismissed as conspiracy theory, became a topic of serious scientific inquiry. Public health officials who demanded compliance with restrictions were caught violating their own rules. Each misstep, each reversal, each appearance of hypocrisy further eroded trust.

"The word 'evidence' has turned into a quasi-religious concept. Politicians claimed they were 'following the science' while making decisions that seemed as much about politics as public health."

— Frank Furedi, Sociologist

As sociologist Frank Furedi observed, "The word 'evidence' has turned into a quasi-religious concept" during COVID-19. Politicians claimed they were "following the science" while making decisions that seemed as much about politics as public health. The blurring of expertise and ideology undermined the very authority officials were trying to assert.

These failures matter because they validate skepticism. When institutions make catastrophic errors, dismissing critics as conspiracy theorists or science deniers becomes harder. A sociologist studying vaccine hesitancy found that it isn't simply about what people believe. It's shaped by what they've experienced: "inequalities, distrust in institutions, and moral values that guide decision-making." Communities facing systemic neglect have little reason to trust public institutions. When institutions fail to deliver basic services, skepticism becomes the default.

An analysis of 50 million vaccine-related social media posts found no single variable explained hesitancy. It's not just misinformation. It's poverty, education gaps, historical neglect, and the accumulated weight of broken promises. States with higher poverty rates and lower educational attainment showed significantly more vaccine resistance—a pattern that speaks to structural failures, not just messaging problems.

As mainstream institutions lost credibility, trust didn't disappear. It migrated to alternative sources—some more reliable than others. This fragmentation has created parallel information ecosystems where different groups inhabit fundamentally different realities.

The rise of "nontraditional new media"—podcasts, blogs, social media influencers—reflects this migration. These sources often feel more authentic, more aligned with audience values, more willing to challenge conventional wisdom. A podcast host who shares your politics and skepticism of elites can feel more trustworthy than a faceless newspaper, even if the host lacks journalistic training or fact-checking resources.

There's a genuine appeal here. Traditional media has its own biases, blind spots, and failures. Corporate consolidation has pushed many outlets toward a conservative bent and increased censorship risks. Local journalism has collapsed, leaving many communities without watchdogs. In this vacuum, alternative sources stepped in.

But the alternative ecosystem has serious problems. Without institutional checks—editorial standards, fact-checking, accountability mechanisms—misinformation flourishes. During Hurricane Sandy, researchers examined 1.8 million tweets and found 10,350 fake images compared to 5,767 real ones. Misinformation dominated early reports. During Hurricanes Harvey and Irma, false claims spread that immigration status checks were being conducted at evacuation sites, deterring undocumented immigrants from seeking safety. In Kerala floods, misleading emergency instructions on WhatsApp and Facebook caused delays in rescue operations.

The fragmented ecosystem also enables targeted manipulation. Climate change deniers don't need to convince everyone—just enough people in key positions to delay action. Anti-vaccination movements don't need to eliminate vaccines—just create enough hesitancy to compromise herd immunity. When different groups trust different sources, coordinated responses to collective challenges become nearly impossible.

Interestingly, one bright spot emerged: a majority of Americans trust public and local stations more than commercial media, according to a July 2025 poll. This suggests that the crisis isn't about media per se, but about commercial incentives, consolidation, and perceived bias. Yet the same summer that poll was released, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting closed after the Trump administration rescinded its funding, eliminating one of the few remaining trusted alternatives.

If this all feels unprecedented, history offers some perspective—and hope. RAND's Truth Decay study noted historical parallels to periods of institutional skepticism in the 1880s-1890s, 1920s-1930s, and 1960s-1970s. In each era, Americans questioned the credibility of elites and established institutions. In each case, society eventually found its footing.

The late 19th century saw robber barons, corrupt political machines, and yellow journalism that made today's media look tame. The response was the Progressive Era: reforms that increased transparency, broke up monopolies, and established professional standards for journalism, science, and government. Investigative reporting rebounded, holding power accountable.

The 1920s-1930s brought the rise of propaganda, mass media manipulation, and economic collapse that discredited experts. The response was the New Deal regulatory state, strengthened institutions, and a post-WWII emphasis on nonpartisan expertise in government and science.

The 1960s-1970s saw Vietnam, Watergate, and widespread distrust of "the Establishment." Yet by the 1980s-1990s, new institutional arrangements emerged: investigative journalism won Pulitzers, academic research became more transparent, and government agencies reformed.

Historical periods of institutional collapse—the 1880s-1890s, 1920s-1930s, and 1960s-1970s—were all followed by reconstruction. Each recovery shared common elements: increased transparency, stronger accountability, and renewed investment in education and media literacy.

Each recovery shared common elements: increased transparency, stronger accountability mechanisms, reformed institutions that earned back trust through improved performance, and renewed investment in education and media literacy. None of these recoveries was quick or easy, but they demonstrate that epistemic authority can be restored.

The question is whether we can do it again. Today's challenges differ in scale and speed. The digital information ecosystem is fundamentally different from anything in the past. Polarization is more entrenched. The global nature of modern problems demands coordination across borders. But history suggests the problem isn't insoluble.

So how do we restore epistemic authority? Researchers and practitioners have proposed several strategies, none of them simple.

Institutional transparency and accountability. Institutions need to open their processes, admit mistakes, and hold themselves accountable. Scientists should share data and methods. Journalists should correct errors prominently. Government agencies should explain their reasoning in plain language. When institutions mess up, acknowledging failure honestly does more for credibility than defensiveness ever could.

Moving beyond hierarchical expertise. Research on epistemic authority in sustainability suggests that rebuilding trust requires shifting from hierarchical models—where experts dictate to the public—to inclusive, participatory, and dialogical approaches. People need to feel involved in knowledge creation, not just lectured to. This means community-based research, citizen science, and genuine public engagement in policy design.

Digital literacy and education. If misinformation thrives because people can't discern credible sources, then education focused on digital literacy becomes essential. Teaching critical thinking, source evaluation, and statistical reasoning can help people navigate the infodemic. This isn't about telling people what to think; it's about giving them tools to think effectively.

Platform accountability and design. Social media companies need to take responsibility for the information ecosystems they've created. Real-time misinformation detection technologies and proactive debunking initiatives have shown promise during disasters. Algorithmic adjustments that deprioritize engagement-driven outrage and prioritize accuracy could help. But this requires political will to regulate platforms that have resisted meaningful reform.

Local, trusted messengers. The vaccine hesitancy research makes clear that communities respond better to leaders they know and trust than to distant institutions or national figures. Rebuilding epistemic authority may require decentralizing it—empowering local doctors, teachers, community leaders, and journalists who have earned trust through relationships, not credentials alone.

Addressing structural inequalities. When poverty, educational gaps, and systemic neglect drive distrust, restoring institutional credibility requires addressing those underlying conditions. Communities that see institutions delivering for them—good schools, economic opportunity, responsive governance—will be more inclined to trust those institutions. This is the hardest solution but perhaps the most important.

Reforming media economics. The media trust crisis is largely a response to commercial media, driven by consolidation, cost-cutting, and the clickbait business model. Restoring trust may require new economic models: reader-supported journalism, revitalized public media, nonprofit news organizations. The collapse of CPB shows how fragile these alternatives are, but also how valued.

The erosion of epistemic authority isn't an abstract academic problem. It has immediate, tangible consequences for the most pressing challenges we face.

Public health: When people don't trust health authorities, vaccination rates drop, disease outbreaks occur, and deaths from preventable illnesses increase. COVID-19 demonstrated how distrust can turn a medical crisis into a political one, costing hundreds of thousands of additional lives.

Climate change: Delayed action on climate has weakened the foundation for evidence-based policymaking on arguably humanity's most consequential challenge. Every year of delay based on manufactured doubt makes the problem harder and costlier to solve.

Democratic governance: When citizens can't agree on basic facts, democracy becomes paralyzed. Collective decision-making requires shared reality. Political paralysis and the collapse of civil discourse don't just make politics unpleasant—they prevent society from addressing problems that require coordinated action.

Emergency response: During natural disasters, misinformation can hamper emergency response, misdirect resources, and distort public perception of disaster severity. When people don't trust official communications, they make decisions that put themselves and others at risk.

Economic stability: Distrust in financial institutions, regulatory agencies, and economic experts contributed to crises and impedes recovery. The 2013 government shutdown's $20 billion economic loss was a direct consequence of the kind of political dysfunction that truth decay enables.

Social cohesion: Beyond specific policy failures, the loss of shared epistemic authority fractures society itself. When we inhabit different realities, empathy becomes harder, compromise seems impossible, and the social trust that holds communities together erodes. We're not just disagreeing about policy anymore—we're disagreeing about what's real.

Looking ahead, the trajectory is concerning. As older generations who still hold institutional trust age out, they'll be replaced by younger cohorts who've never known a world where mainstream institutions commanded broad credibility. The 17-point trust gap between those under 50 and those over 65 suggests baseline trust will continue declining.

Technological changes will accelerate these trends. Artificial intelligence can now generate convincing text, images, audio, and video—deepfakes that make it nearly impossible to verify what's real. Personalized AI assistants will curate information tailored to individual preferences, potentially creating billions of customized reality bubbles.

Political incentives push the same direction. Leaders who benefit from distrust in institutions have every reason to keep attacking them. Partisan media ecosystems reward outrage over accuracy. Foreign adversaries amplify division because a fractured America is a weakened one.

Yet the future isn't predetermined. Every historical period of institutional collapse was followed by reconstruction. Society figured out how to rebuild trust, not because it was easy, but because the alternative was unacceptable.

Right now, we're at an inflection point. The collapse of traditional epistemic authority is nearly complete. What comes next will determine whether we slide into a post-truth society where power and persuasion replace evidence and expertise, or whether we build new forms of authority that earn trust through transparency, inclusion, and performance.

Michael D. Rich's call to action after RAND's Truth Decay report feels even more urgent today: "We urge individuals and organizations to join with us in promoting the need for facts, data and analysis in civic and political discourse—and in American public life." That's not a plea for blind faith in experts. It's a recognition that without some shared basis for determining what's true, collective action becomes impossible.

The institutions that once served as our epistemic authorities—media, science, government—earned their status through demonstrated competence and accountability. They lost it through failure, complacency, and detachment from the communities they claimed to serve. Restoring that authority won't come from demanding deference. It will come from institutions proving, day by day, that they deserve trust again.

Whether they can do so may be the defining challenge of this generation. Because a society that can't agree on what's real is a society that can't solve its problems. And we have plenty of problems that won't wait for us to figure this out.

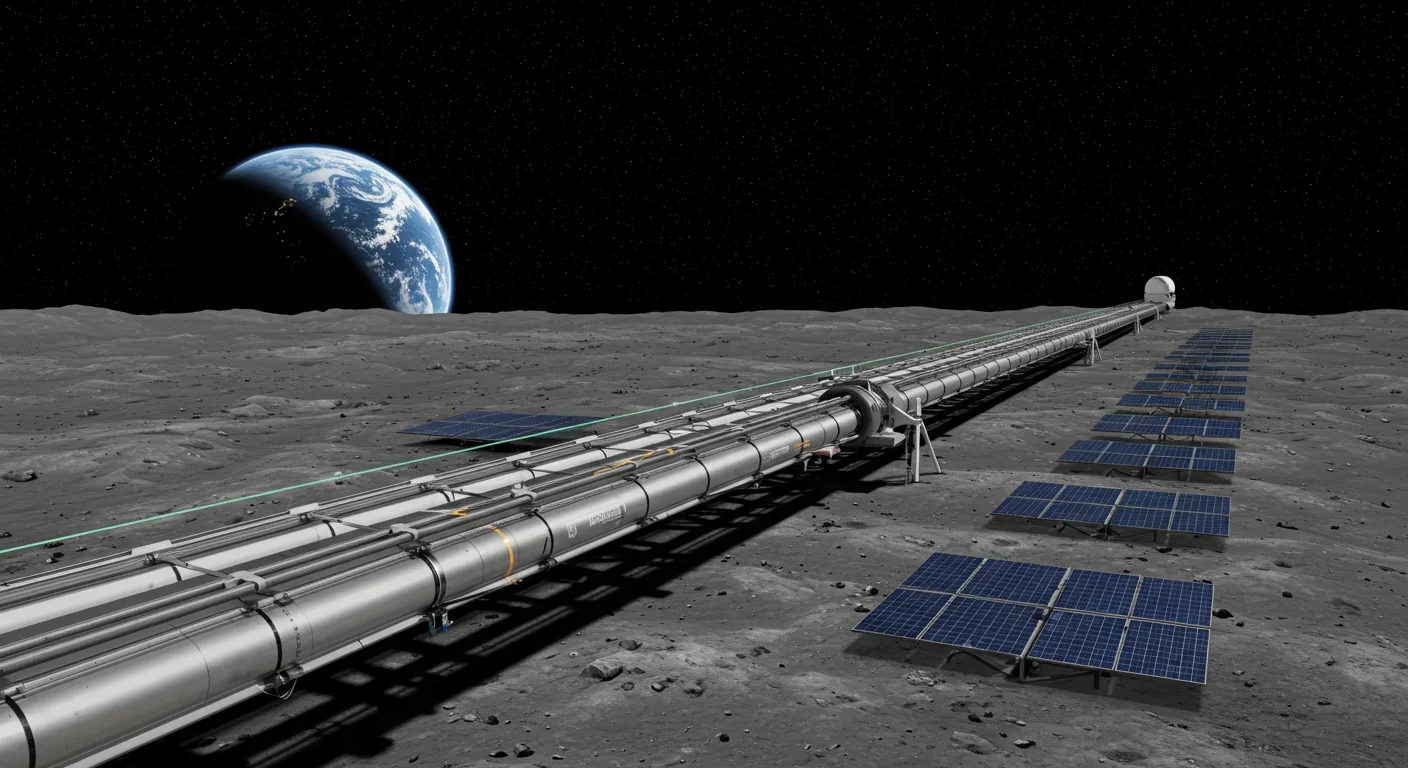

Lunar mass drivers—electromagnetic catapults that launch cargo from the Moon without fuel—could slash space transportation costs from thousands to under $100 per kilogram. This technology would enable affordable space construction, fuel depots, and deep space missions using lunar materials, potentially operational by the 2040s.

Ancient microorganisms called archaea inhabit your gut and perform unique metabolic functions that bacteria cannot, including methane production that enhances nutrient extraction. These primordial partners may influence longevity and offer new therapeutic targets.

CAES stores excess renewable energy by compressing air in underground caverns, then releases it through turbines during peak demand. New advanced adiabatic systems achieve 70%+ efficiency, making this decades-old technology suddenly competitive for long-duration grid storage.

Human children evolved to be raised by multiple caregivers—grandparents, siblings, and community members—not just two parents. Research shows alloparenting reduces parental burnout, improves child development, and is the biological norm across cultures.

Soft corals have weaponized their symbiotic algae to produce potent chemical defenses, creating compounds with revolutionary pharmaceutical potential while reshaping our understanding of marine ecosystems facing climate change.

Generation Z is the first cohort to come of age amid a polycrisis - interconnected global failures spanning climate, economy, democracy, and health. This cascading reality is fundamentally reshaping how young people think, plan their lives, and organize for change.

Zero-trust security eliminates implicit network trust by requiring continuous verification of every access request. Organizations are rapidly adopting this architecture to address cloud computing, remote work, and sophisticated threats that rendered perimeter defenses obsolete.