Why Your Brain Is Hardwired to Lose Money

TL;DR: Human children evolved to be raised by multiple caregivers—grandparents, siblings, and community members—not just two parents. Research shows alloparenting reduces parental burnout, improves child development, and is the biological norm across cultures.

When exhausted parents post about feeling overwhelmed on social media, the most common response is often some variation of "it takes a village." It's meant to be comforting, but what if this phrase isn't just a nice sentiment—what if it's describing our actual biological design?

For most of human history, children had about 20 caregivers interacting with them daily. Not just parents. Not just nuclear families. Grandmothers, aunts, older siblings, neighbors, friends—an entire network of adults sharing the monumental task of raising the next generation. Anthropologists call this alloparenting, and it's not some cultural quirk. It's how humans evolved to raise children.

The modern Western ideal of two parents raising kids in isolated households? That's the actual anomaly. And mounting research suggests this mismatch between our evolutionary design and contemporary reality is contributing to parental burnout, maternal depression, and developmental challenges for children. Understanding alloparenting isn't just an academic exercise—it's a roadmap for why parenting feels so impossibly hard right now, and what we can do about it.

Alloparenting refers to any parental care provided by individuals other than the biological parents—grandparents, siblings, extended family, or even non-relatives. The term was first coined by anthropologist Sarah Blaffer Hrdy in her 1975 PhD thesis, and her decades of research has fundamentally reshaped how we understand human development.

Here's the evolutionary logic: Human infants are exceptionally demanding. We wean our babies around 2-3 years, significantly faster than other great apes who take 5-7 years. We also have shorter intervals between births—about 3.1 years in natural fertility populations compared to 5.5 years for chimpanzees. This means human mothers are often caring for multiple dependent children simultaneously, something nearly impossible without help.

Cooperative breeding, as this system is known, allowed our ancestors to have more children who survived to adulthood. The alloparents—those "other mothers" and caregivers—didn't just help out occasionally. They were essential. Studies of contemporary hunter-gatherer societies show that alloparents provide almost half of a child's care.

In hunter-gatherer societies studied today, alloparents provide nearly 50% of child care—demonstrating this isn't cultural preference but biological necessity.

Among the Efe people of the Democratic Republic of Congo, infants have an average of 14 alloparents per day by 18 weeks old, and are passed between caregivers eight times an hour. In the Aka community of tropical forest foragers, infants interact with about 20 caregivers daily. This isn't neglect or instability—it's highly responsive care with someone always within a few meters of the child.

One of the most compelling pieces of evidence for alloparenting comes from an unusual feature of human biology: menopause. Humans are one of only a handful of species where females routinely live decades beyond their reproductive years. Why would evolution favor this?

The grandmother hypothesis proposes that post-menopausal women increased their evolutionary fitness not by having more children, but by helping raise their grandchildren. Studies have shown this effect dramatically. In rural Gambia, the presence of a maternal grandmother significantly reduced child mortality. Research across nine populations found that grandmothers provided between 1.2% and 14.3% of total childcare, freeing mothers to return to fertility sooner.

But grandmothers aren't just babysitters—they're specialists. They bring decades of knowledge about which plants are edible, how to read weather patterns, how to soothe a colicky baby. They provide emotional support that reduces maternal depression. In evolutionary terms, investing energy in grandchildren rather than additional offspring could yield higher returns for passing on genes.

"Humans evolved to rely on assistance from group members other than the mother, using the term 'allomother' to refer to any female or male other than the mother who helps to care for an infant."

— Sarah Blaffer Hrdy, Anthropologist

This isn't just about older women either. Alloparenting involves fathers, siblings, aunts, uncles, and even non-relatives. Among the Nso people of Cameroon, mothers actively discourage exclusive bonding, encouraging children to form attachments with many caregivers so the child "is used to everybody and loves everybody equally." This ensures continuity of care even if one caregiver becomes unavailable.

The benefits of alloparenting extend far beyond just giving parents a break. Children raised with multiple caregivers show measurable developmental advantages.

First, there's the sheer amount of attention. Hunter-gatherer infants are in physical contact with someone for about 90% of daylight hours, and almost every crying bout receives an immediate response. Compare that to Western childcare regulations, where ratios might be one adult to three or four infants. In alloparenting systems, the ratio often exceeds 10 caregivers to one child.

This constant availability allows for incredibly responsive care without burning out any single caregiver. When one adult needs rest, another seamlessly steps in. The child experiences consistency and attention, while caregivers maintain their own wellbeing.

Children with multiple attachment figures develop greater social competence. They learn to read different personalities, adapt their behavior to various social contexts, and develop what researchers call "theory of mind"—the ability to understand that other people have different perspectives and knowledge. These are foundational skills for navigating complex human societies.

Research shows that children who experience alloparenting demonstrate better emotional regulation and resilience. When facing stress with their primary caregiver, they have other trusted adults to turn to. This doesn't dilute attachment—it enriches it. Children learn that the world contains multiple sources of safety and support.

Children with multiple secure attachments don't experience divided loyalty—they experience enriched development, learning to navigate diverse relationships and perspectives from an early age.

Siblings benefit too. In many alloparenting cultures, children begin helping care for younger siblings as early as age four. This isn't exploitation—it happens through play in mixed-age groups where older children naturally model caregiving behaviors. These early experiences foster empathy, responsibility, and nurturing skills that serve them throughout life.

If alloparenting is our evolutionary norm, the modern nuclear family represents a radical and recent experiment—one that's showing serious cracks.

The nuclear family as we know it emerged during industrialization and suburbanization, particularly in Western societies. Economic changes pulled families apart. Jobs required mobility, moving people away from extended family networks. Suburban housing developments created physical distance between households. Cultural narratives celebrated independence and self-sufficiency.

By the mid-20th century, the ideal became a married couple raising 2.5 kids in a single-family home, preferably with the mother as primary caregiver. Attachment theory, while valuable in many ways, was interpreted to mean that children needed one primary caregiver—ideally the mother—to thrive. This fueled what researchers call "intensive mothering": the belief that mothers bear total responsibility for meeting every child's need.

The consequences have been predictable. Parental burnout rates are climbing. Maternal depression affects one in seven women postpartum. Parents report profound loneliness even while spending all their time with their children. The phrase "drowning in the shallow end" captures it perfectly—the tasks aren't individually overwhelming, but the relentlessness without support becomes crushing.

"Such narratives can lead to maternal exhaustion and have dangerous consequences."

— Dr. Nikhil Chaudhary, Evolutionary Anthropologist

Dr. Nikhil Chaudhary, an evolutionary anthropologist, warns that intensive mothering narratives "can lead to maternal exhaustion and have dangerous consequences." We're asking parents to fulfill a role that humans never evolved to do alone, then blaming them when they struggle.

Looking at childcare practices worldwide reveals just how unusual Western nuclear family norms really are.

In many Indian, African, and Latin American cultures, extended family households remain common. Multiple generations live together or in close proximity, with grandparents, aunts, and uncles naturally sharing childcare responsibilities. Children grow up surrounded by adults and cousins, experiencing constant social engagement.

Among the Tajik people, mothers, grandmothers, aunts, neighbors, and older siblings are described as "available, interchangeable, and responsive." Children of all ages surround infants, interacting and providing care. This distributes the workload while ensuring the infant receives continuous attention.

In Israeli kibbutzim, communal childcare was historically a core value, with children spending days in communal houses cared for by trained caregivers while parents worked. Though the system has evolved, it demonstrates that non-parental care from familiar, consistent caregivers can support healthy development.

Even within Western contexts, immigrant communities often maintain alloparenting networks. Studies show that access to extended family support correlates with better maternal mental health outcomes and lower stress across diverse populations.

The through-line across all these examples is the same: humans thrive when childcare is treated as a shared community responsibility rather than a private family burden.

So what do we do with this information? Most people can't move back to their hometown to be near extended family, and we can't recreate hunter-gatherer village life in modern cities. But we can apply alloparenting principles in practical ways.

Build your village intentionally. Research shows that alloparents don't have to be biological relatives. Religious communities, close friends, and "fictive kin" like godparents can all serve alloparenting roles. Look for other parents in similar situations—neighbors, coworkers, people from your faith community—and propose regular childcare swaps or shared activities.

Embrace multi-age social groups. Modern culture segregates children by exact age in schools and activities. This is unnatural and limits developmental benefits. Seek out opportunities for your children to interact with kids of various ages—mixed-age playgroups, family gatherings, community events. Older children learn by teaching younger ones, and younger children benefit from older role models.

Ask for help and accept it graciously. The data shows that having emotional support from family or friends reduces maternal depression. Yet many parents hesitate to ask for help, fearing they'll appear incompetent. Reframe it: you're not failing by needing support—you're acknowledging your biology. When someone offers to help, say yes.

Asking for help isn't a sign of weakness—it's recognition of how humans are designed to parent. Our ancestors never did this alone, and neither should we.

Advocate for structural changes. Individual solutions only go so far. We need policy changes that recognize the importance of alloparenting: affordable quality childcare, flexible work arrangements that allow extended family involvement, paid family leave for grandparents, community spaces designed for intergenerational interaction.

Rethink childcare as an investment, not a cost. Many parents calculate that childcare costs nearly equal one parent's salary, so one stays home. But this often leads to isolation and missed career opportunities. If childcare provides access to community, adult interaction, and shared caregiving—essentially creating an alloparenting network—it may be worth prioritizing even at financial sacrifice.

Normalize multiple attachment figures. If your child bonds deeply with a grandparent, daycare provider, or family friend, that's not competition or threat—it's a developmental advantage. Children with multiple secure attachments do better, not worse. Encourage these relationships.

Include fathers and partners fully. Research on alloparenting historically focused on women, but fathers and other male caregivers play crucial roles. Equal partnership in childcare isn't just fair—it's providing children with diverse attachment figures and caregiving styles.

The nuclear family isn't wrong, and two-parent households can absolutely raise healthy, happy children. But the research on alloparenting reveals that the intense pressure and isolation many modern parents experience isn't a personal failure—it's a societal design flaw.

Humans evolved as cooperative breeders. Our babies expect to be surrounded by multiple caring adults. Our biology assumes that caregiving burdens will be shared, allowing any single caregiver time to rest, pursue other activities, and maintain their own wellbeing. For hundreds of thousands of years, this is how we did it.

The good news is that we're not locked into our current arrangements. Small changes can make substantial differences: regular dinners with extended family, childcare co-ops with neighbors, multi-generational housing, employer support for family leave, communities designed for spontaneous interaction rather than isolation.

When you feel overwhelmed by parenting, when you wonder why this feels so impossibly hard, remember: you're not supposed to do this alone. You weren't designed for it. Your children weren't designed for it. Every generation before the modern era had something we've lost—and are slowly learning to rebuild.

It really does take a village. Not as a poetic metaphor, but as a biological fact. The question isn't whether we need alloparenting—we do. The question is how we recreate those networks in modern life, honoring our evolutionary heritage while adapting to contemporary reality.

The village may look different now—less geographic, more intentional, cobbled together from various sources rather than given by default. But the fundamental principle remains: children thrive when raised by a community of invested caregivers, and parents thrive when they don't carry the burden alone.

Maybe it's time we stopped trying to do the impossible, and started building the support systems humans actually need.

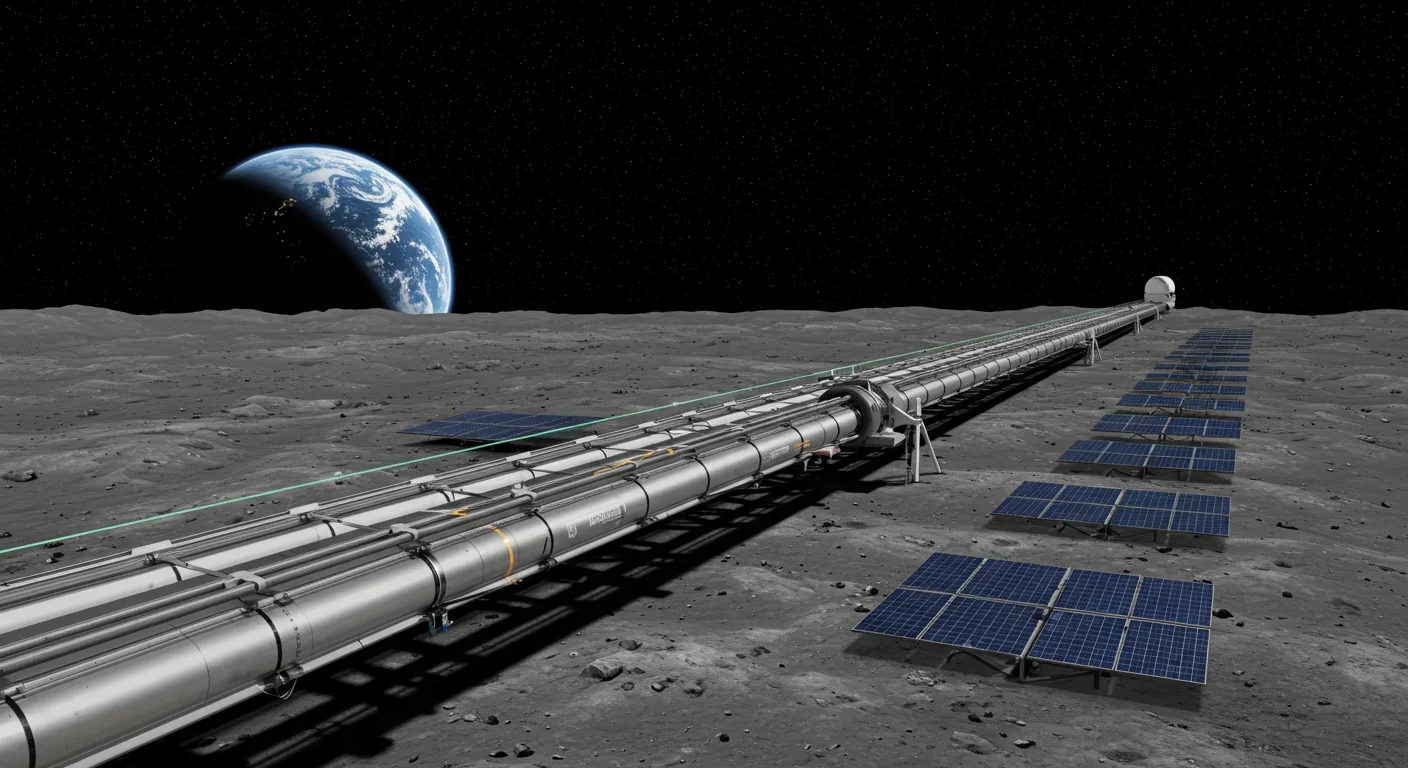

Lunar mass drivers—electromagnetic catapults that launch cargo from the Moon without fuel—could slash space transportation costs from thousands to under $100 per kilogram. This technology would enable affordable space construction, fuel depots, and deep space missions using lunar materials, potentially operational by the 2040s.

Ancient microorganisms called archaea inhabit your gut and perform unique metabolic functions that bacteria cannot, including methane production that enhances nutrient extraction. These primordial partners may influence longevity and offer new therapeutic targets.

CAES stores excess renewable energy by compressing air in underground caverns, then releases it through turbines during peak demand. New advanced adiabatic systems achieve 70%+ efficiency, making this decades-old technology suddenly competitive for long-duration grid storage.

Human children evolved to be raised by multiple caregivers—grandparents, siblings, and community members—not just two parents. Research shows alloparenting reduces parental burnout, improves child development, and is the biological norm across cultures.

Soft corals have weaponized their symbiotic algae to produce potent chemical defenses, creating compounds with revolutionary pharmaceutical potential while reshaping our understanding of marine ecosystems facing climate change.

Generation Z is the first cohort to come of age amid a polycrisis - interconnected global failures spanning climate, economy, democracy, and health. This cascading reality is fundamentally reshaping how young people think, plan their lives, and organize for change.

Zero-trust security eliminates implicit network trust by requiring continuous verification of every access request. Organizations are rapidly adopting this architecture to address cloud computing, remote work, and sophisticated threats that rendered perimeter defenses obsolete.