The Polycrisis Generation: Youth in Cascading Crises

TL;DR: Nearly 300 cities worldwide will shrink by 2040, forcing urban planners to abandon growth-based models. Cities like Leipzig, Detroit, and Youngstown are pioneering 'degrowth urbanism'—rightsizing infrastructure, converting vacant lots to green space, and consolidating services for smaller populations.

By 2040, nearly 300 cities worldwide will have smaller populations than they do today. That's not a crisis forecast from pessimists—it's the new reality urban planners are designing for. What started as desperate triage in Detroit and Youngstown has become something more intriguing: a deliberate experiment in whether cities can thrive by doing the unthinkable, which is planning to get smaller. Degrowth urbanism flips traditional planning on its head, asking what happens when success means not expanding but instead becoming better at being smaller.

Traditional urban planning operates on a simple assumption: growth equals success. More residents mean more tax revenue, justifying bigger budgets for services and infrastructure. But degrowth urbanism challenges this entire framework. Instead of treating population loss as failure, it accepts demographic realities and asks how cities can maintain quality of life with fewer people.

The difference is fundamental. Where conventional planning tries to attract people back, degrowth strategies focus on right-sizing infrastructure to match current populations. Where traditional approaches view vacant buildings as problems waiting for redevelopment, degrowth planners see opportunities for green space, urban agriculture, or strategic demolition.

This isn't just semantic reframing. It's a completely different approach to municipal governance. Rather than spreading services thin across a dwindling tax base, cities consolidate. Rather than maintaining oversized infrastructure systems, they redesign them. The goal shifts from maximizing population to maximizing livability.

The story of shrinking cities follows remarkably similar patterns worldwide. Manufacturing centers that exploded in the mid-20th century—Detroit, Youngstown, Leipzig, dozens of Japanese cities—built infrastructure for populations that peaked and never returned.

Leipzig lost nearly 20% of its population between 1990 and 1998 as reunification triggered mass migration to western Germany. Detroit's population dropped from 1.8 million in 1950 to under 700,000 today. Youngstown, Ohio shrank from 170,000 to 65,000 over the same period. These weren't gradual declines—they were demographic collapses.

What made shrinkage particularly painful was the mismatch between population and infrastructure. Cities designed water systems, built roads, and planned transit for populations double or triple their current size. Maintaining oversized infrastructure with shrinking tax bases created a vicious cycle: higher per-capita costs drove remaining residents away, further shrinking the tax base.

Japan faces perhaps the starkest version of this challenge. With rural municipalities losing up to 50% of their population, entire neighborhoods sit empty while schools, clinics, and transit systems operate far below capacity. The country is pioneering "compact city" strategies that consolidate residents into smaller, more efficiently serviced urban cores.

Not all shrinkage looks the same. Rust Belt cities lost manufacturing jobs but retained some population. European cities faced suburbanization combined with emigration. Japanese cities confront aging without immigration. Each pattern requires different planning responses.

But here's what's interesting: not all shrinkage looks the same. Rust Belt cities lost manufacturing jobs but retained some population. European cities faced suburbanization combined with emigration. Japanese cities confront aging without immigration. Each pattern requires different planning responses.

If any city proves degrowth urbanism can work, it's Leipzig. After hemorrhaging residents through the 1990s, the German city stopped chasing growth and started planning for shrinkage.

The strategy had several components. First, Leipzig incorporated surrounding municipalities between 1994 and 2001, expanding its footprint even as core population fell. This allowed the city to redistribute residents more efficiently rather than watching neighborhoods hollow out.

Second, the city pursued aggressive redevelopment of industrial sites and civic infrastructure. The old Zentralstadion was demolished and rebuilt as a modern football stadium. Wilhelminian-era quarters received targeted investment. Rather than spreading resources across the entire city, Leipzig focused on making specific districts highly livable.

Third—and this is crucial—Leipzig accepted that some areas would depopulate. Instead of fighting to maintain every neighborhood, planners let some areas naturally consolidate while transforming others into green space or light industrial use.

The results surprised everyone. By 2001, Leipzig's population stabilized and then began growing again, not because planners chased growth but because they'd created a city that worked well at smaller scale. Young people, artists, and professionals moved in, attracted by affordable housing in well-maintained districts.

"Leipzig demonstrates something counterintuitive: accepting shrinkage can position a city for renewal. By not overextending resources trying to maintain unsustainable infrastructure, the city preserved fiscal health."

— Urban planning analysis from Leipzig case studies

Leipzig demonstrates something counterintuitive: accepting shrinkage can position a city for renewal. By not overextending resources trying to maintain unsustainable infrastructure, the city preserved fiscal health. By concentrating investment, it created vibrant pockets that attracted new residents organically.

When Youngstown, Ohio released its 2010 master plan, it did something no American city had done before: it explicitly planned for a smaller population.

The Youngstown 2010 plan acknowledged the city would continue losing residents and designed accordingly. Rather than spreading services across all neighborhoods, it identified priority areas for investment and areas that would transition to other uses.

The strategy involved controversial choices. Some neighborhoods would receive intensive support—new parks, improved services, infrastructure upgrades. Others would be gradually decommissioned, with remaining residents encouraged to relocate to priority zones. Vacant lots would become urban agriculture, green stormwater management, or simply return to nature.

This required confronting uncomfortable realities. City officials had to tell residents that their neighborhoods weren't priorities. They had to acknowledge that maintaining infrastructure everywhere wasn't financially viable. The political backlash was intense.

But Youngstown's plan influenced cities nationwide. It proved American municipalities could have honest conversations about decline. It provided a framework for matching infrastructure to population rather than clinging to past peaks. It showed that planning for shrinkage wasn't admitting defeat—it was adapting to reality.

The outcomes have been mixed. Some neighborhoods successfully transformed. Community gardens and green space improved quality of life. But implementation proved harder than planning. Residents resisted relocation. Political leadership changed. External funding dried up. Youngstown remains shrinking, though perhaps more intentionally than before.

The hardest part of degrowth urbanism isn't philosophical—it's technical. How do you redesign systems built for 200,000 people when only 100,000 remain?

Take water infrastructure. Pipes sized for peak demand don't flow properly at lower volumes. Water sits longer, creating water quality issues. Treatment plants operate inefficiently below design capacity. Distribution networks designed for dense populations waste energy pumping water long distances to scattered users.

Flint, Michigan's experience illustrates these challenges. The city's infrastructure crisis stemmed partly from operating systems designed for 200,000 residents with barely 100,000 remaining. Rightsizing meant not just fixing pipes but fundamentally redesigning water distribution.

Transit faces similar problems. Bus routes serving sparse populations can't justify frequent service. Light rail built for rush-hour crowds runs empty. Cities must choose between maintaining existing infrastructure inefficiently or investing in redesign for uncertain future demand.

Edmonton, Alberta offers one approach. Rather than maintaining sprawling suburban infrastructure indefinitely, the city is pursuing compact development patterns that allow infrastructure efficiency. The strategy isn't abandoning suburbs but gradually increasing density in core areas while letting peripheral infrastructure decline through natural obsolescence.

Roads and utilities present different challenges. Unlike water systems, roads don't stop functioning when populations fall. They just become expensive to maintain. Cities must decide which streets to keep paved, which to convert to gravel, which to close entirely. These aren't just technical decisions—they're statements about which neighborhoods matter.

One unexpected benefit of shrinking cities: abundant land for green infrastructure experiments.

Detroit has over 100,000 vacant lots. Rather than viewing them as blight, degrowth planners see them as opportunities. Urban agriculture, stormwater management, habitat restoration, renewable energy—all uses that wouldn't fit in growing cities become possible.

The transformation isn't just aesthetic. Green stormwater infrastructure in vacant lots reduces flooding and improves water quality. Urban forests cool neighborhoods experiencing heat island effects from abandoned buildings. Community gardens provide food and gathering spaces.

Urban agriculture in shrinking cities takes forms impossible elsewhere. Not just community gardens but actual commercial farming operations. Former industrial sites become orchards. Vacant blocks become market farms. This isn't weekend hobbyist gardening—it's agricultural production integrated into urban fabric.

Pittsburgh's deconstruction pilot project demonstrates another approach. Rather than demolishing vacant buildings and hauling debris to landfills, the city carefully dismantles structures, salvaging materials for reuse. It's urban mining—treating abandoned buildings as resource deposits.

Rewilding represents the most radical transformation. Rather than maintaining manicured parks that require ongoing resources, some cities are letting nature reclaim vacant areas, creating wildlife corridors through former residential neighborhoods.

Rewilding represents the most radical transformation. Rather than maintaining manicured parks that require ongoing resources, some cities are letting nature reclaim vacant areas. Ecological succession creates wildlife corridors through former residential neighborhoods.

China's sponge city initiative offers a large-scale model. Cities like Wuhan and Xiamen are transforming impervious surfaces into permeable landscapes that absorb rainfall, recharge groundwater, and reduce flooding. While not specifically degrowth projects, sponge cities demonstrate how urban contraction could incorporate sophisticated ecological design.

The challenge is ensuring these transformations benefit current residents rather than becoming green gentrification. Community engagement matters. Residents must shape what happens in their neighborhoods, not just accept plans developed elsewhere.

Here's the brutal arithmetic shrinking cities face: infrastructure costs are largely fixed while revenue is population-dependent.

A water treatment plant costs roughly the same to operate whether serving 100,000 or 200,000 people. Police and fire protection still require stations distributed across the city. Roads deteriorate regardless of traffic volume. As population falls, per-capita costs rise.

Traditional responses make things worse. Raising taxes drives more residents away, accelerating decline. Cutting services reduces quality of life, making the city less attractive. Deferring maintenance creates infrastructure disasters.

Degrowth urbanism confronts this through consolidation. By concentrating residents and services, cities can maintain quality while reducing coverage area. This requires difficult decisions about which neighborhoods to prioritize, but it's fiscally sustainable in ways universal service isn't.

Infrastructure rightsizing delivers long-term savings. Smaller water systems cost less to operate and maintain. Compact transit serves fewer route-miles more frequently. Consolidated service districts reduce staffing needs.

But transition costs are substantial. Decommissioning infrastructure isn't free. Relocating residents requires assistance. Demolition costs money. Cities need upfront investment to achieve long-term savings—precisely when budgets are tightest.

External funding becomes crucial. Federal and state support for infrastructure transitions. Foundation grants for experimental green infrastructure. Private investment in redevelopment districts. Shrinking cities rarely can fund transformation alone.

Revenue diversification helps. Rather than depending entirely on property taxes, cities pursue creative funding models. Land banks monetize vacant property. Green infrastructure generates environmental credits. Deconstruction operations recover material value.

Leipzig's experience suggests fiscal sustainability is achievable. By stabilizing population through smart consolidation, the city maintained revenue while reducing infrastructure obligations. Quality of life improvements in priority districts attracted middle-class residents, strengthening the tax base.

Japan's shrinking city challenge dwarfs anything Western nations face. Over 900 municipalities are projected to lose population by 2040, with some rural areas facing 50% declines.

The response is "compact city" policy—essentially degrowth urbanism at national scale. Cities designate core areas for concentrated investment while letting peripheral neighborhoods naturally depopulate.

The strategy involves relocating facilities to encourage consolidation. Schools, clinics, and shops move to urban centers. Public housing concentrates in service-rich districts. Transit focuses on connecting compact cores rather than serving sprawl.

Incentives encourage voluntary relocation. Residents who move from peripheral areas to city centers receive housing subsidies and tax breaks. Property in depopulating areas is purchased at fair market value, preventing residents from being trapped by worthless real estate.

"Some areas will cease being urban. Japan is confronting a reality most nations avoid: planned abandonment isn't failure, it's adaptation to demographic inevitability."

— Japanese urban planning researchers

What happens to vacated areas? Some become parks. Some return to agriculture or forestry. Some are simply abandoned to nature. Japan is confronting a reality most nations avoid: some areas will cease being urban.

The social challenges are profound. Elderly residents who've lived in the same home for decades face pressure to relocate. Communities that existed for generations dissolve. The psychological impact of planned abandonment is significant.

But the alternative is worse. Spreading services across vast, sparsely populated areas is financially impossible and delivers poor outcomes. Compact cities at least ensure remaining residents receive adequate services.

Early results are mixed. Some cities successfully consolidated. Others struggled with implementation. Residents resist relocation. Political resistance from peripheral communities is intense. The experiment continues.

Degrowth urbanism's greatest vulnerability is who makes decisions about which areas shrink.

When planners designate priority and non-priority zones, they're essentially determining which neighborhoods have futures. These decisions have profound equity implications. If priority areas align with wealthy neighborhoods while poor areas are left to decline, degrowth becomes state-sponsored abandonment.

Detroit's experience illustrates the problem. As the city prioritized certain districts, residents of neglected areas felt betrayed. They'd paid taxes for decades, maintained their homes, invested in their communities. Now planners told them their neighborhoods weren't worth saving.

The process matters as much as the outcome. Top-down planning imposed without community input breeds resentment. Residents must meaningfully participate in decisions about their neighborhoods' futures.

Youngstown learned this through painful trial and error. Initial plans faced backlash because residents felt excluded. Revised approaches involved extensive community engagement, though this slowed implementation.

Environmental justice adds another layer. If green infrastructure and rewilding projects displace low-income residents through green gentrification, they reproduce the same inequities they're meant to address.

One approach is community land trusts that give residents ownership stakes in redevelopment. If community gardens or green space increase property values, longtime residents benefit rather than being displaced by newcomers.

Another is ensuring relocated residents receive adequate support. Relocation assistance, housing subsidies, and guaranteed service levels in new neighborhoods matter. If relocation means losing community connections without gaining quality of life, it's not equitable.

The fundamental question is whether degrowth planning empowers communities to shape their futures or becomes a mechanism for concentrating disinvestment in already vulnerable areas.

Shrinking cities stumbled into environmental wins nobody planned for.

Lower population density means reduced emissions. Fewer residents drive less. Consolidated transit serves riders more efficiently. Abandoned industrial sites stop polluting.

Green infrastructure in vacant lots provides ecosystem services. Trees sequester carbon and reduce heat islands. Permeable surfaces manage stormwater and recharge groundwater. Urban agriculture reduces food miles.

Rewilding projects create biodiversity corridors through urban cores. Native plants return. Wildlife populations recover. Ecological processes that disappeared under dense development restart.

The most significant environmental benefit might be demonstrating that human wellbeing doesn't require endless growth. If shrinking cities can be livable and sustainable, they challenge growth-dependent models of urban development.

But it's not automatic. Abandoned buildings can create environmental hazards. Vacant lots become illegal dumping sites. Without deliberate management, decline produces degradation not regeneration.

The carbon footprint question is complicated. If population doesn't disappear but relocates to sprawling suburbs, shrinking cities just export emissions elsewhere. True environmental benefits require people living in compact, efficient communities.

Urban agriculture's climate impact isn't as straightforward as it seems. Transportation savings offset by infrastructure intensity, especially in northern climates requiring season extension. Best practices matter—native plantings, organic methods, water efficiency.

The most significant environmental benefit might be demonstrating that human wellbeing doesn't require endless growth. If shrinking cities can be livable, sustainable, even desirable, they challenge growth-dependent models of urban development.

Technology might make degrowth urbanism more manageable. Smart city systems provide data for rightsizing decisions.

Sensors in water infrastructure detect where flow patterns indicate underutilized capacity. Transit data shows which routes serve too few riders. Energy consumption maps reveal where consolidation would maximize efficiency.

Predictive analytics can model demographic scenarios, helping planners anticipate where population will stabilize versus continue declining. This allows proactive rather than reactive infrastructure decisions.

Geographic information systems help identify optimal boundaries for service consolidation. Rather than arbitrary political boundaries, planners can design districts around actual usage patterns.

Digital engagement platforms facilitate community participation at scale. Residents can visualize proposals, provide feedback, and track implementation. This addresses the engagement challenge inherent in degrowth planning.

AI tools are being tested for flood prevention in sponge city concepts, optimizing where green infrastructure delivers maximum benefit. Similar approaches could guide green transformation in shrinking cities.

The risk is techno-solutionism—believing algorithms can resolve inherently political decisions. Data informs choices but doesn't make them. Communities must still decide which neighborhoods to prioritize, who bears transition costs, what kind of city they want to become.

Urban agriculture in shrinking cities isn't quaint community gardens—it's large-scale food production.

Detroit has over 1,500 urban farms and gardens utilizing vacant land that would otherwise sit empty. Some operations are commercial ventures selling to restaurants and markets. Others are nonprofits addressing food insecurity.

The architectural integration goes beyond sticking gardens in empty lots. Buildings are designed with agriculture in mind—rooftop farms, vertical growing systems, aquaponics integrated into structures.

Best practices make the difference between genuinely sustainable agriculture and greenwashed gardening. Soil remediation in formerly industrial areas. Water-efficient drip systems. Season extension without excessive energy. Native pollinator plantings.

The social benefits extend beyond food production. Community gardens provide gathering spaces in neighborhoods losing commercial and civic anchors. Youth employment programs teach agricultural skills. Educational initiatives connect urban kids to food systems.

But challenges persist. Land tenure remains uncertain—what happens when vacant lots urban farmers cultivate get redeveloped? Zoning regulations designed for different eras don't accommodate agriculture. Access to capital and markets is limited.

Some cities are formalizing support. Land banks lease vacant property to farmers on long-term agreements. Zoning updates explicitly permit agricultural uses. Municipal programs provide composting infrastructure and technical assistance.

The transformation from vacant lots to vibrant farms represents one of degrowth urbanism's most visible successes. It converts liabilities into assets, blight into productivity, abandonment into opportunity.

Traditional planning assumes knowable futures. Degrowth planning embraces uncertainty.

Nobody knows if shrinking will continue, stabilize, or reverse. Demographic projections are notoriously unreliable over decades. Economic conditions change. Climate migration could repopulate some shrinking cities while emptying others.

Adaptive planning creates flexible frameworks rather than fixed blueprints. Infrastructure designed for multiple scenarios. Zoning that accommodates various densities. Phased implementation allowing course corrections.

Modular infrastructure can expand or contract with demand. Transit systems using buses can adjust routes and frequencies more easily than fixed rail. Water systems with distributed treatment can add or subtract capacity.

Reversible interventions allow cities to test approaches without permanent commitment. Temporary green infrastructure can revert to development if population returns. Pilot programs in specific districts demonstrate feasibility before citywide implementation.

The key is building resilience rather than optimization. Systems optimized for specific conditions fail when circumstances change. Resilient systems maintain functionality across a range of scenarios.

This requires different evaluation criteria. Instead of maximizing efficiency, planners prioritize adaptability. Instead of minimizing cost, they value flexibility. Instead of permanent solutions, they create evolutionary frameworks.

So does degrowth urbanism represent visionary adaptation or defeatism disguised as planning?

The optimistic view: cities accepting demographic realities position themselves for sustainable futures. By rightsizing infrastructure, concentrating investment, and embracing green transformation, they create livable communities that don't depend on endless growth.

Leipzig's renaissance suggests this works. The city didn't just survive shrinkage—it thrived by accepting and planning for it. Quality of life improvements attracted new residents, creating virtuous cycles.

The pessimistic view: degrowth is managed decline. Cities give up on growth because they've failed to compete. Rather than addressing root causes—economic stagnation, lack of opportunity, failing schools—they rationalize contraction as strategy.

Youngstown's ongoing struggles support this interpretation. Planning for shrinkage didn't reverse decline. The city continues losing population, just with prettier parks in abandoned neighborhoods.

The realistic view: it depends on execution. Degrowth urbanism isn't inherently good or bad. Done well, with robust community engagement, fiscal discipline, and creative design, it can transform struggling cities into sustainable communities. Done poorly, it becomes state-sponsored abandonment concentrating disinvestment in vulnerable areas.

What's clear is that growth-obsessed planning doesn't serve shrinking cities. Maintaining infrastructure for populations that won't return is financially ruinous and delivers poor services. The question isn't whether to adapt but how.

As demographic transitions spread—Japan's aging, Europe's suburbanization, America's regional population shifts—more cities will confront shrinkage. The experiments happening now in Detroit, Leipzig, Youngstown, and Japanese municipalities aren't curiosities. They're previews of challenges facing hundreds of cities worldwide.

The cities that navigate this successfully won't be those that resist hardest but those that adapt smartest. They'll embrace the counterintuitive truth that planning for less can create more—more livability, more sustainability, more opportunity within new constraints.

Degrowth urbanism asks us to reimagine what successful cities look like. Maybe they're not endless skylines and sprawling suburbs. Maybe they're compact, green, efficiently served communities where quality of life matters more than quantity of people. That's not managed decline. That's intentional design for the realities of the 21st century.

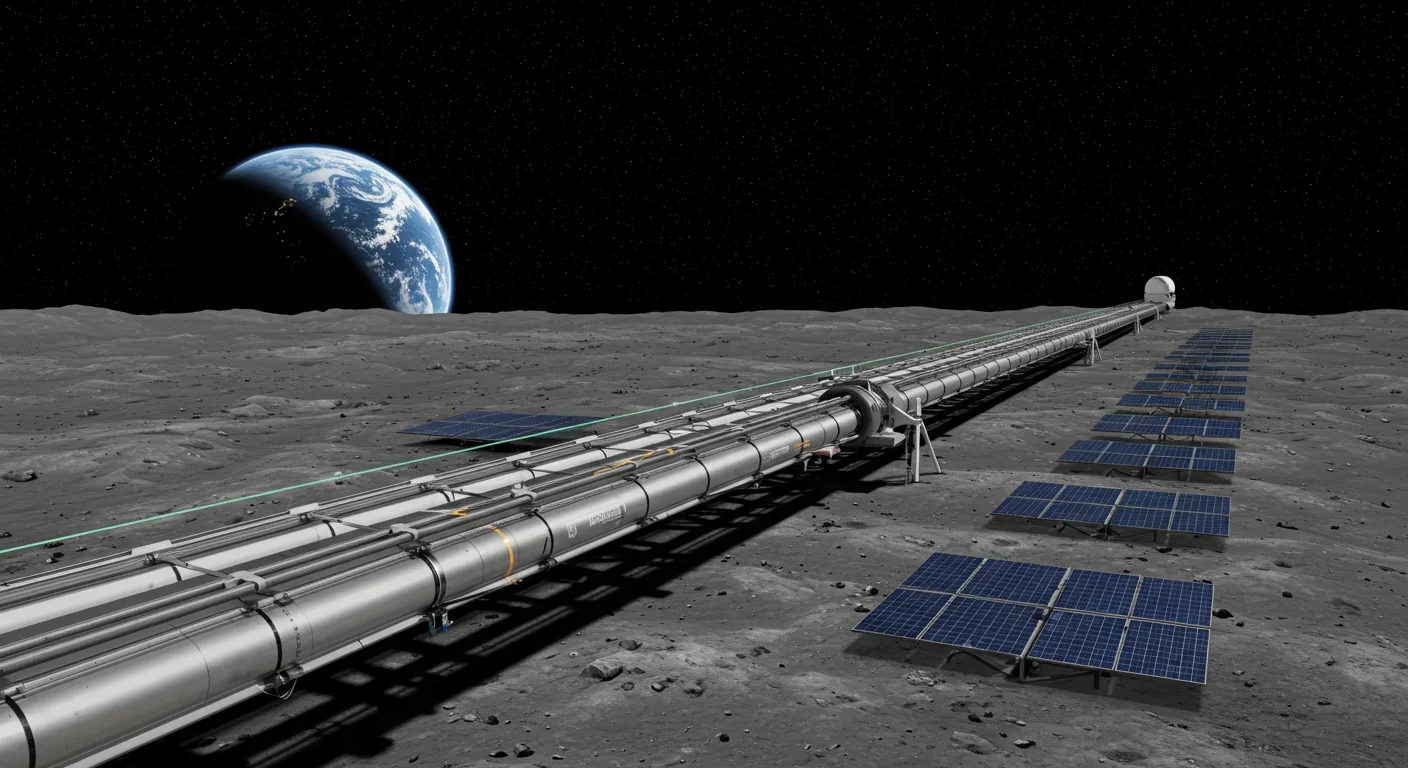

Lunar mass drivers—electromagnetic catapults that launch cargo from the Moon without fuel—could slash space transportation costs from thousands to under $100 per kilogram. This technology would enable affordable space construction, fuel depots, and deep space missions using lunar materials, potentially operational by the 2040s.

Ancient microorganisms called archaea inhabit your gut and perform unique metabolic functions that bacteria cannot, including methane production that enhances nutrient extraction. These primordial partners may influence longevity and offer new therapeutic targets.

CAES stores excess renewable energy by compressing air in underground caverns, then releases it through turbines during peak demand. New advanced adiabatic systems achieve 70%+ efficiency, making this decades-old technology suddenly competitive for long-duration grid storage.

Human children evolved to be raised by multiple caregivers—grandparents, siblings, and community members—not just two parents. Research shows alloparenting reduces parental burnout, improves child development, and is the biological norm across cultures.

Soft corals have weaponized their symbiotic algae to produce potent chemical defenses, creating compounds with revolutionary pharmaceutical potential while reshaping our understanding of marine ecosystems facing climate change.

Generation Z is the first cohort to come of age amid a polycrisis - interconnected global failures spanning climate, economy, democracy, and health. This cascading reality is fundamentally reshaping how young people think, plan their lives, and organize for change.

Zero-trust security eliminates implicit network trust by requiring continuous verification of every access request. Organizations are rapidly adopting this architecture to address cloud computing, remote work, and sophisticated threats that rendered perimeter defenses obsolete.