The Polycrisis Generation: Youth in Cascading Crises

TL;DR: IVF and fertility treatments now cost $23,000-$30,000 per cycle in America, creating a two-tier reproductive system where wealthy families overcome infertility while working-class couples face permanent childlessness or catastrophic debt. With only 15 states mandating IVF coverage and 69% of employers offering no fertility benefits, economic inequality has become biological inequality.

Sarah and Marcus always imagined they'd have children. They'd talk about baby names on long drives, debate school districts, and plan family vacations they'd take someday. But after three years of trying, watching their friends' pregnancy announcements roll through social media, they finally heard the diagnosis: infertility. Their doctor recommended IVF. The solution existed. It just cost more than their car.

For millions of Americans, parenthood has become a luxury item. While wealthy families can overcome biological barriers with cutting-edge reproductive technology, working-class couples face a stark choice: go into catastrophic debt or abandon their dreams of children altogether. This isn't just about medicine anymore. It's about who gets to participate in one of humanity's most fundamental experiences.

The fertility treatment gap represents something unprecedented in American inequality: a biological divide enforced by economics. And it's widening.

A single round of IVF costs between $23,000 and $30,000 in the United States, not counting medications, genetic testing, or the countless appointments leading up to the procedure. That's the base price. Most people need multiple cycles. The average patient requires two to three attempts before achieving pregnancy, pushing the real cost closer to $60,000 or $90,000.

Want to preserve your fertility for later? Egg freezing runs $3,325 to over $50,000 depending on how many cycles you need and where you live. Add annual storage fees of $500 to $1,000. When you're ready to use those eggs, you'll pay for IVF on top of everything else.

These numbers dwarf typical family budgets. The median household income in America hovers around $75,000. Spending $30,000 on a single medical procedure means wiping out savings, maxing credit cards, or choosing between fertility treatment and a down payment on a house.

The median American household would need to spend 40% of their annual income on a single IVF cycle — before medications, testing, or any additional procedures.

Meanwhile, international comparisons reveal how uniquely expensive American fertility care has become. IVF costs around $5,000 in Greece, $6,000 in Spain, and $8,000 in the Czech Republic. Canada charges up to $20,000 CAD per cycle, but even that's cheaper than the U.S. when you factor in medication costs. Thailand has emerged as a fertility tourism hub precisely because treatment costs 60% less than in Western countries.

The wealthy don't just pay these prices. They barely notice them. But for everyone else, the math is impossible.

Whether your insurance covers fertility treatment depends almost entirely on where you happen to live and work. As of September 2023, 21 states plus Washington, D.C. have passed fertility insurance coverage laws, but only 15 of those mandates actually include IVF itself. The rest cover fertility preservation or diagnostic services but stop short of the most expensive interventions.

Live in Massachusetts? Your large-group health plan must cover IVF. Cross the border into New Hampshire and you're on your own. Move from Illinois to Indiana and your coverage evaporates. These aren't small differences. They're the difference between having children or not.

Currently, 31% of employers offer fertility benefits, with 30% covering IVF specifically. That sounds promising until you realize which employees get those benefits. Corporate professionals working for large tech companies, consulting firms, and financial institutions receive comprehensive fertility coverage. Retail workers, teachers, restaurant staff, and small business employees typically get nothing.

The disparity reinforces itself. High earners work for companies that attract talent with premium benefits, including fertility coverage. Lower-wage workers not only lack coverage but also can't afford to pay out of pocket. The system concentrates reproductive capacity among the already privileged.

"Infertility treatment coverage can make IVF more accessible and affordable, preventing people from going into debt or forgoing building their family altogether."

— Maven Clinic healthcare policy analysis

State mandates help, but they're riddled with exclusions. Arkansas requires that eggs be fertilized with a spouse's sperm, effectively barring LGBTQ couples and single parents. Other states impose age limits, require proof of infertility duration, or cap the number of covered cycles so low they're essentially symbolic.

Colorado offers one of the nation's strongest mandates: large employers must cover up to three egg retrievals with unlimited embryo transfers. But "large employers" means companies with 100+ employees. Everyone else falls through the gap.

Here's what fertility clinics don't advertise: your odds of success correlate directly with how much you can spend. It's not just about affording treatment. It's about affording optimal treatment.

CDC data shows that IVF success rates vary significantly by age, egg source, and clinic quality. Women under 35 using their own eggs have cumulative success rates around 50% per retrieval. By age 42, that drops to under 10%. Donor eggs dramatically improve outcomes, but they add $25,000 to $50,000 to the bill.

Wealthy patients can afford strategies that multiply their chances. They pursue multiple cycles simultaneously, use preimplantation genetic testing to screen embryos ($3,000 to $7,000 extra), bank eggs when young before fertility declines, and travel to top-rated clinics regardless of location. They can afford to fail and try again.

Low-income patients get one shot. Maybe two if they're lucky. They can't afford genetic screening, so they implant embryos that may carry chromosomal abnormalities. They can't bank eggs in their 20s because they're focused on paying rent. They choose cheaper clinics with lower success rates because those are the ones they can reach.

Wealth doesn't just buy fertility treatment — it buys multiple attempts, genetic screening, top clinics, and the ability to keep trying until it works. Economic inequality becomes biological inequality.

The result? Higher-income patients achieve pregnancy more reliably, not because their bodies are more fertile, but because they can afford to iterate. They can afford the best doctors, the best protocols, and the ability to keep trying until it works.

America isn't alone in this struggle, but the international comparison reveals how policy shapes access. Many European countries offer partial or full coverage for fertility treatments, though implementation varies wildly.

The United Kingdom's National Health Service covers fertility treatment, but local municipalities control administration. Guidelines say IVF should be available up to age 42, but a BBC investigation found that 80% of UK regions fail to meet that standard. Budget constraints mean waitlists stretch for years. Some couples age out of eligibility while waiting.

France covers four IVF cycles for women under 43 through its national health system. Belgium provides six cycles of reimbursement. Israel goes further than almost anywhere, covering unlimited IVF attempts until a woman has two living children, regardless of age or marital status. Israel's fertility rate of 3.0 children per woman far exceeds the developed-world average, suggesting policy actually works.

But even in countries with universal healthcare, gaps persist. Canada's provinces offer patchwork coverage. Most Canadians pay out of pocket for treatment, forcing many to travel to the U.S. for better options or to Europe for cheaper ones. Ireland stands out as the only EU nation with zero state funding, leaving residents to pay €4,000 to €6,500 per cycle entirely on their own.

Australia operates a rebate system where government insurance covers portions of treatment but excludes crucial services like egg retrieval. The result? Significant out-of-pocket costs that still exclude lower-income families.

Fertility tourism has exploded as patients chase affordable care. Americans fly to Spain, Mexico, and Thailand. Canadians head south. Europeans travel east to Czech Republic and Greece. The phenomenon reveals a global market failure: reproductive technology exists, it works, but pricing and policy prevent equitable access.

Let's zoom out and look at what happens when fertility treatment becomes a luxury good. We're not just watching individual couples suffer. We're witnessing the emergence of a new kind of demographic stratification.

Rising childlessness is already driving the decline in U.S. birth rates. But it's not evenly distributed. High-income professionals are delaying childbearing, then using technology to catch up later. Lower-income families who face infertility simply don't have children.

The long-term implications are profound. Wealth already transfers across generations through inheritance, education access, and social networks. Now it transfers through biology itself. Families with resources can overcome infertility, age-related fertility decline, genetic conditions, and same-sex biology. Families without resources cannot.

"The higher the degree of education and GDP per capita of a human population, the fewer children are born in any developed country."

— Income and fertility research, Wikipedia demographic analysis

This doesn't mean rich people are having more kids overall. Income and fertility show an inverse correlation at the population level. Wealthier nations have lower birth rates. But at the individual level, wealth determines who can have children when they choose to, versus who gets locked out by biology and economics combined.

We're creating a system where childlessness becomes increasingly concentrated among the poor. Not by choice, but by financial constraint. That has cascading effects on inequality, social mobility, and family structure across generations.

The U.S. fertility services market was valued at $8.6 billion in 2023 and continues growing at 9% annually. By 2030, analysts project it will exceed $13 billion. Global fertility treatment market is expected to hit $85.53 billion by 2034.

Someone is profiting from desperation.

Fertility clinic owners report median incomes ranging from $200,000 to well over $500,000 annually. Private equity has begun acquiring clinics, consolidating the market, and standardizing pricing at premium levels. The Boston Globe reported that private equity involvement is one reason IVF costs keep rising despite technological maturity that should drive prices down.

The industry argues that complexity justifies cost. IVF requires sophisticated laboratories, specialized embryologists, constant monitoring, and expensive medications. All true. But those same factors exist in other countries where treatment costs a quarter of U.S. prices. The difference isn't complexity. It's that American healthcare operates on a profit-maximizing model with limited regulation on pricing.

Medication costs demonstrate the problem starkly. Fertility drugs can run $3,000 to $6,000 per cycle. The same medications cost far less in Canada and Europe. American patients effectively subsidize global pharmaceutical profits.

Meanwhile, less than 25% of fertility patients have insurance coverage that meaningfully offsets costs. Most pay entirely out of pocket. That creates a captive market where providers face little pressure to compete on price. Desperate patients will pay what they must.

Some clinics offer payment plans and financing options, but those just convert unaffordable lump sums into unaffordable debt. Fertility financing programs charge interest rates that compound the financial burden. You don't just pay for treatment. You pay for the privilege of going into debt for it.

The data tells one story. Living through it tells another.

Consider Jennifer, a 33-year-old public school teacher who learned she had endometriosis that had damaged her fallopian tubes. Her doctor said IVF was her only realistic option. Her insurance, provided by the school district, classified infertility as a "lifestyle issue" and covered nothing. The treatment would cost more than she earned in six months. She and her husband took out a personal loan at 12% interest. After two failed cycles, they were $45,000 in debt with no baby. They stopped trying.

Or Marcus, who survived cancer at 28 and lost his fertility to chemotherapy. His oncologist recommended sperm banking before treatment, but his insurance didn't cover it. Neither did the charity fund he applied to. He couldn't afford $1,500 while facing cancer treatment bills. Years later, cancer-free and married, he learned that donor sperm costs $600 to $1,200 per vial, plus IVF expenses. His cancer survival came with permanent childlessness.

Then there's Aisha and Maya, a same-sex couple who needed donor sperm regardless of fertility status. They faced the same IVF costs as heterosexual couples, plus sperm bank fees, storage costs, and legal expenses. Six attempts and $78,000 later, they had one child. They'd planned on two, but the money simply ran out.

These aren't edge cases. Millions of people face family formation blocked by checkbook limits, not biological impossibility. The technology exists, proved and refined. It's just priced beyond reach.

These aren't edge cases. These are millions of people whose family formation is blocked by checkbook limits, not biological impossibility. The technology to help them exists, proved, refined, and routine. But it's priced beyond reach.

Political attention to fertility treatment access has increased, particularly after the 2022 Dobbs decision raised questions about IVF's legal status. Several policy proposals have emerged, though most remain more symbolic than substantive.

In February 2025, President Trump signed an executive order titled "Expanding Access to In Vitro Fertilization," directing federal agencies to review barriers to IVF access and explore ways to reduce costs. Follow-up fact sheets outlined potential tax credits, regulatory streamlining, and research funding. Another announcement in October 2025 highlighted efforts to lower IVF costs specifically.

Whether these proposals translate into meaningful access depends entirely on implementation. Tax credits help middle-class families but do nothing for low-income couples who don't have $30,000 to front. Regulatory streamlining might reduce costs marginally but won't address the fundamental economics.

Some Democratic lawmakers have proposed requiring insurance coverage for fertility treatments nationwide, similar to state mandates but with federal enforcement. Republicans generally oppose insurance mandates as government overreach, preferring market-based solutions and tax incentives. The political divide means comprehensive reform remains unlikely.

Progressive advocates push for treating infertility as a medical condition deserving the same coverage as diabetes or heart disease. Conservative voices worry that mandated coverage will raise premiums for everyone and object on religious grounds to certain reproductive technologies. The debate stalls while millions wait.

A few states are expanding coverage. Connecticut, Delaware, and Maryland have strengthened mandates in recent years. But progress is slow and uneven. For every state that expands access, several others do nothing or actively restrict it through political battles over embryo rights and abortion regulations that create legal uncertainty around IVF.

While policy stagnates, some employers have stepped in to fill the gap. Tech companies led the way, with firms like Google, Meta, and Apple offering comprehensive fertility coverage including IVF, egg freezing, surrogacy, and adoption assistance. They frame it as competitive advantage: attract top talent, support diverse family structures, reduce turnover.

The business case is real. Offering fertility benefits improves employee recruitment and retention, particularly among millennial and Gen Z workers who prioritize family-friendly policies. Companies report that the cost of coverage is offset by reduced turnover, which saves far more than fertility treatments cost.

But employer-sponsored benefits reach only a fraction of workers. Just 31% of employers offer any fertility benefits, concentrated among large corporations. Small businesses can't afford to compete. Service industry workers, gig economy contractors, and part-time employees have zero access.

"Employers can play a key role in removing barriers to access by offering IVF coverage, which improves employee retention, attracts top talent, and enhances workplace diversity."

— Maven Clinic employer benefits research

This creates yet another disparity. Software engineers and management consultants get fertility coverage. Home health aides and warehouse workers don't. The gap mirrors and amplifies existing wage inequality. High earners get both higher pay and better benefits that enable family formation. Low earners get neither.

Some argue that's how markets work. Valuable employees command better compensation packages. But fertility isn't like a gym membership or free snacks. It's about whether you can have children. Tying that to employment status means reproductive capacity becomes a luxury benefit, distributed according to career success.

Employers who offer fertility benefits also must navigate complex implementation. Do they cover same-sex couples and single parents? Surrogacy? How many IVF cycles? What age limits? Every decision creates inclusion or exclusion, often along lines employers would rather not draw explicitly.

Looking internationally, the countries with the most equitable fertility access share certain features. They treat infertility as a medical condition, not a lifestyle choice. They regulate clinic pricing to prevent gouging. They integrate fertility coverage into existing universal healthcare systems. They provide support earlier, before couples spend years and savings on failed attempts.

Israel's success shows what robust policy looks like. By covering unlimited IVF attempts, the nation removed financial barriers entirely. The result isn't just higher birth rates. It's that birth rates stay relatively even across income levels. Wealth still confers advantages, but biology and economics are partially decoupled.

Belgium's six-cycle reimbursement system achieves high success rates while controlling costs. By covering multiple attempts, they reduce pressure for risky multiple-embryo transfers, which leads to healthier pregnancies and lower downstream healthcare costs from premature births.

Even imperfect systems offer lessons. The UK's NHS coverage demonstrates that even with budget constraints and waitlists, public provision beats pure market approaches. Canada shows that without federal coordination, provincial patchworks leave gaps. Ireland proves that wealthy nations can still fail entirely to address the issue.

American exceptionalism in healthcare extends to fertility. We spend more per capita than any nation but leave more people uncovered. We have cutting-edge technology but the least equitable access. We celebrate medical innovation while millions can't afford to use it.

Thirty years from now, we'll look back at this era and recognize it as a turning point. Either we'll have made reproductive technology accessible, treating it as basic healthcare, or we'll have cemented a permanent fertility divide where biological parenthood correlates strongly with economic class.

The technology isn't going away. It's getting better. Gene editing, artificial gametes, and advanced embryo screening are coming. Each innovation will be priced for maximum profit, accessible first to the wealthy, and eventually trickling down to others or not, depending on policy choices we make now.

We're also approaching a moment where employment-based coverage becomes increasingly irrelevant. The gig economy, remote work, and career mobility are eroding the employer-healthcare link. Whatever replaces it will either include fertility coverage or it won't. That decision will shape American demographics for generations.

Some worry that subsidizing fertility treatment encourages population growth when we should be addressing overpopulation and climate change. But that's a separate debate. The question here isn't whether more people should be born. It's whether the people who want children and would be good parents should be prevented by cost alone.

Others argue that adoption offers an alternative, and they're not wrong. But adoption comes with its own costs ($20,000 to $50,000), bureaucratic barriers, and emotional complexity. It's a beautiful option but not a perfect substitute for those who want biological children. And the underlying question remains: why should either path be blocked by economics?

Achieving genuine equity in fertility treatment access requires multiple interventions working together. No single policy fixes this.

Universal coverage: Treat infertility as a medical condition covered by insurance, period. Set federal standards requiring coverage comparable to other serious health conditions. Let states exceed minimums but not fall below them.

Price regulation: Cap what clinics can charge for standard IVF cycles, similar to how other countries control drug pricing. Require transparency in billing. Ban surprise fees and exploitative financing.

Public funding: Create grant programs for low-income families, similar to Section 8 housing vouchers but for fertility treatment. Cover multiple cycles to provide realistic success chances.

Research investment: Fund research into making treatments cheaper and more effective. The technology exists to reduce costs dramatically if that becomes a policy priority.

Employer incentives: Offer tax credits to small businesses that provide fertility benefits, leveling the playing field with large corporations.

Anti-discrimination protections: Prevent state mandates from excluding LGBTQ couples, single parents, or other groups. Coverage should be based on medical need, not family structure.

Education and prevention: Increase awareness of fertility preservation options, particularly for young people facing medical treatments that threaten fertility. Subsidize egg and sperm banking for medical necessity.

None of this is particularly radical. It's catching America up to where many peer nations already are. It requires political will, budget allocation, and agreement that reproductive capacity shouldn't be distributed by income.

Here's what makes this issue so uncomfortable: we're generally okay with economic inequality in most areas. Rich people have nicer cars, bigger houses, better vacations. That's capitalism. We accept it, even defend it.

But children? Is parenthood just another consumer good, distributed by market forces?

Most people, across the political spectrum, instinctively say no. Family formation feels different from buying luxury goods. It's fundamental to human flourishing, social fabric, and personal identity in ways that defy easy commodification.

Yet we've built a system that treats it exactly like a luxury purchase. We let market dynamics price people out of parenthood. We accept that the wealthy overcome biological barriers while others just live with them. We permit a two-tier reproductive system and politely avoid calling it what it is: reproductive inequality.

The technology to fix this exists. The money exists. The question is whether we believe reproductive capacity should be rationed by wealth or guaranteed as a basic dimension of human dignity and healthcare access.

That's not a medical question. It's a values question. And right now, our answer is clear, even if we won't say it out loud: in America, building a family is a privilege you purchase, not a right you exercise.

The $50,000 baby isn't a hypothetical anymore. It's the lived reality for millions. The only question is whether we're comfortable with what that says about us.

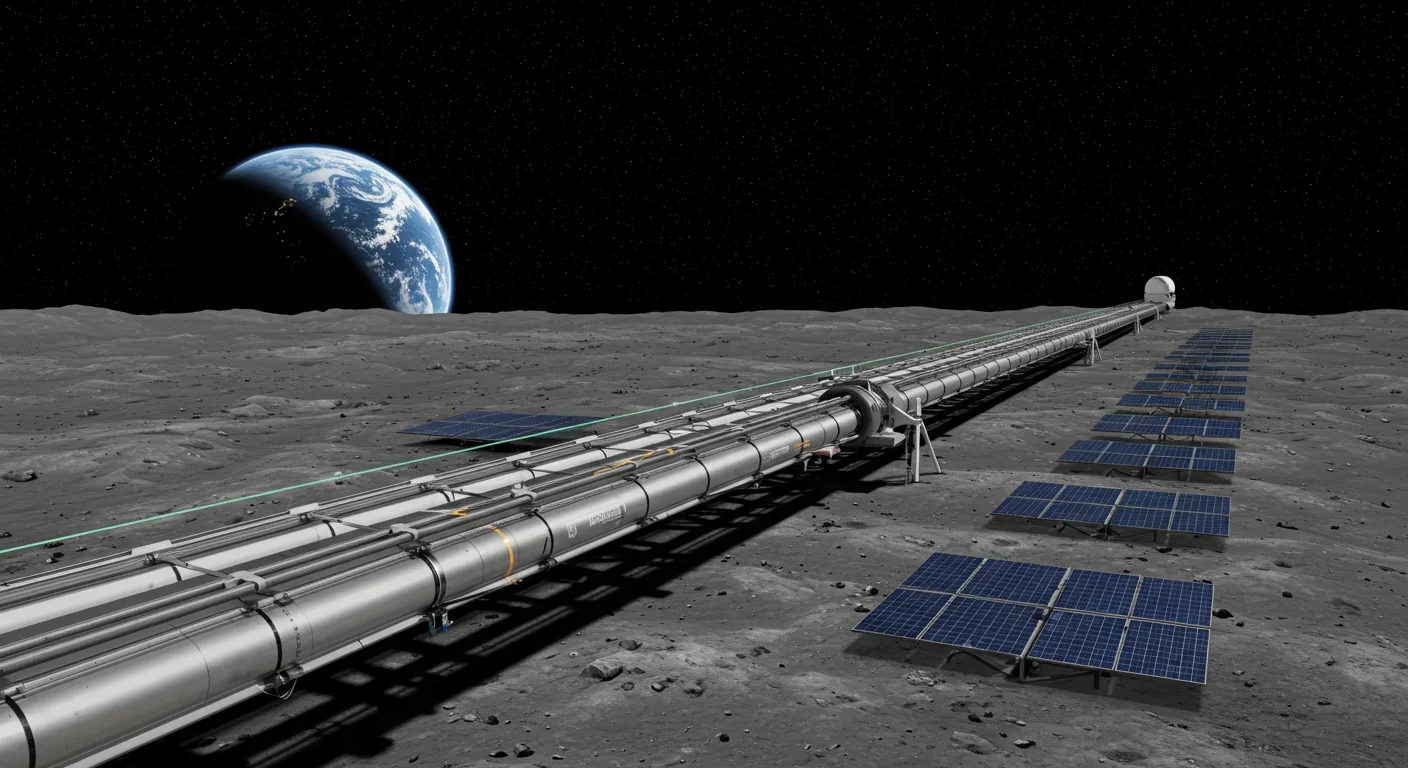

Lunar mass drivers—electromagnetic catapults that launch cargo from the Moon without fuel—could slash space transportation costs from thousands to under $100 per kilogram. This technology would enable affordable space construction, fuel depots, and deep space missions using lunar materials, potentially operational by the 2040s.

Ancient microorganisms called archaea inhabit your gut and perform unique metabolic functions that bacteria cannot, including methane production that enhances nutrient extraction. These primordial partners may influence longevity and offer new therapeutic targets.

CAES stores excess renewable energy by compressing air in underground caverns, then releases it through turbines during peak demand. New advanced adiabatic systems achieve 70%+ efficiency, making this decades-old technology suddenly competitive for long-duration grid storage.

Human children evolved to be raised by multiple caregivers—grandparents, siblings, and community members—not just two parents. Research shows alloparenting reduces parental burnout, improves child development, and is the biological norm across cultures.

Soft corals have weaponized their symbiotic algae to produce potent chemical defenses, creating compounds with revolutionary pharmaceutical potential while reshaping our understanding of marine ecosystems facing climate change.

Generation Z is the first cohort to come of age amid a polycrisis - interconnected global failures spanning climate, economy, democracy, and health. This cascading reality is fundamentally reshaping how young people think, plan their lives, and organize for change.

Zero-trust security eliminates implicit network trust by requiring continuous verification of every access request. Organizations are rapidly adopting this architecture to address cloud computing, remote work, and sophisticated threats that rendered perimeter defenses obsolete.