Care Worker Crisis: Low Pay & Burnout Threaten Healthcare

TL;DR: Participatory budgeting (PB) hands residents direct control over public spending decisions, transforming democracy from spectator sport to active governance. Born in Porto Alegre, Brazil, in 1989, PB has spread to over 11,500 cities worldwide, delivering measurable outcomes: improved infrastructure, increased civic trust, and redistributive justice. Yet PB faces challenges—digital divides, political resistance, and sustainability concerns—that require intentional equity design and community organizing to overcome. The choice is clear: continue closed-door budgeting or embrace participatory processes that share power, build trust, and deliver tangible results.

In Porto Alegre, Brazil, a revolutionary experiment began in 1989 that would fundamentally change how democracy functions in cities worldwide. Residents in impoverished neighborhoods—cut off from water, sanitation, and basic services—were handed direct control over how millions of public dollars would be spent. Within eight years, sewer connections jumped from 75% to 98% of households. The number of schools quadrupled. Infant mortality dropped by 1 to 2 deaths per 1,000 infants. This wasn't charity. It was participatory budgeting (PB), and it proved that when ordinary people control the purse strings, extraordinary things happen.

Today, over 11,500 cities, states, schools, and institutions across five continents have adopted participatory budgeting. From New York City's $24 million annual capital budget allocations to Paris's €75 million PB process, the model has evolved from a grassroots Brazilian innovation into a global governance standard. Yet despite this explosive growth, PB remains misunderstood, underutilized, and vulnerable to political resistance. As democracy faces unprecedented challenges—with 73% of Americans believing elected officials don't respect ordinary people's opinions—participatory budgeting offers a tangible answer: give communities direct power over public resources, and trust will follow.

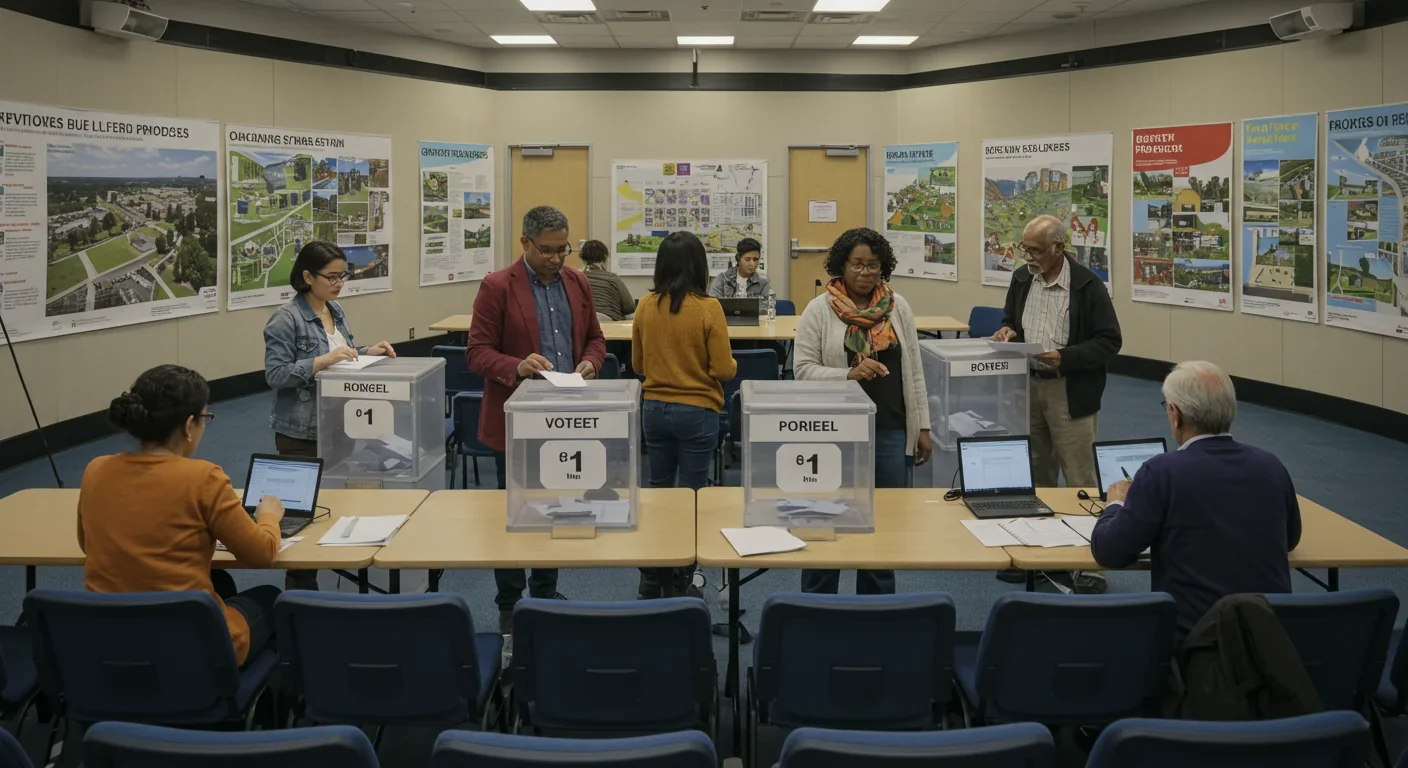

Participatory budgeting is deceptively simple: a democratic process where residents directly decide how to spend part of a public budget. Unlike traditional representative democracy, where elected officials allocate funds behind closed doors, PB opens the books and hands the pen to constituents. The process typically unfolds in four stages: idea generation (residents propose projects), evaluation (committees assess feasibility and costs), voting (community members select winning projects), and implementation (government executes the decisions).

What makes PB revolutionary isn't just transparency—it's accountability with teeth. In New York City's program, residents aged 11 and older can vote regardless of immigration status, using 19 forms of ID and ballots translated into 12 languages. In Denver's People's Budget, voting stations were set up in county jails and homeless shelters, explicitly including incarcerated and unhoused residents. This isn't symbolic inclusion; it's structural power redistribution. When 16,552 residents in Newham, UK, engaged through hybrid digital-physical platforms between 2021-2023, 89% reported feeling more connected to their local area, and 84% felt genuinely involved in decision-making.

The data validates the promise. A comprehensive World Bank study of 253 Brazilian municipalities found that PB contributed to a 269% increase in own-source revenues from 1988 to 2004, as residents who saw their priorities funded began paying taxes more reliably. Research across Brazil, Italy, and the United States demonstrates statistically significant increases in voter turnout, public meeting attendance, and trust in local authorities wherever PB takes root. Even residents who don't directly participate benefit: municipalities using PB generate more local tax revenue because constituents believe government is working on their behalf and can be held accountable.

To understand why participatory budgeting matters now, we must revisit its origins. In 1989, Brazil was emerging from 21 years of military dictatorship. The Workers' Party, led by future president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, won control of Porto Alegre's city government facing a fiscal crisis and deep social inequity. One-third of Porto Alegre's 1.5 million residents lived in favelas without running water, sewers, schools, or medical facilities. Traditional governance had failed them. The party's radical solution: hand budget decisions directly to the people.

The first participatory budgeting cycle in Porto Alegre was messy and experimental. Neighborhood assemblies debated priorities, elected delegates, and ranked projects using a Quality-of-Life Index that weighted investments toward areas with the greatest need. By the mid-1990s, participation surged to 50,000 residents annually—roughly 3.3% of the eligible population, a turnout rate that would be considered exceptional in many municipal elections. The tangible results—quadrupled schools, near-universal water access, plummeting infant mortality—validated the model's redistributive power.

Yet Porto Alegre also illuminates PB's fragility. After the Workers' Party lost power in 2004, a conservative coalition maintained the surface structures of participatory budgeting while gutting its substance, reverting to favor-trading and elite capture. By 2017, PB was effectively suspended. Ethnographic research in Porto Alegre's Partenon district shows that the erosion of PB shifted social movements from institutionalized participation back toward proximity politics and bureaucratic activism—strategies that keep communities engaged but with far less formal power.

This historical arc parallels other technological revolutions that promised democratization. The printing press decentralized knowledge, the internet promised equal access to information, and blockchain evangelists tout trustless governance. Each innovation encountered entrenched power structures that adapted to neutralize disruptive potential. PB is no different: it only works when governments genuinely share power, and that willingness is always contingent, always contested.

Let's demystify the mechanics. A successful participatory budgeting process requires six essential components:

1. Budget Allocation: Cities typically dedicate 0.5% to 2% of their total budget to PB. Cleveland's 2023 ballot initiative mandated 2% of the city's General Fund annually—about $30.8 million in ARPA funds initially. Helsinki allocated €8.8 million in 2021, representing 0.2% of the city budget. Smaller pilots, like Edmonton's Balwin and Belvedere neighborhoods, started with $69,000 across six projects. The size matters less than consistency: successful programs grow incrementally based on demonstrated results.

2. Outreach and Accessibility: This is where most PB initiatives succeed or fail. Newham's Co-create platform combined Go Vocal digital tools with in-person deliberation, achieving a five-fold increase in engagement over previous cycles. Asheville, North Carolina, responding to Hurricane Helene's devastation, built a recovery engagement hub that reached 7,000 residents through multi-channel outreach—weekly emails (74.3% open rate), standing voicemail lines for residents without internet, and translated materials. Equity-focused design means explicitly targeting marginalized groups: youth, immigrants, people with disabilities, formerly incarcerated individuals, and non-English speakers.

3. Idea Generation: Community members submit proposals for capital projects—park improvements, school upgrades, street repairs, public art installations. In New York City's 2024 cycle, 346 proposals emerged across participating districts. Viña del Mar, Chile, received 89 project ideas, of which 44 were deemed admissible. Crowdsourcing platforms, neighborhood assemblies, and workshop sessions all serve as idea funnels. The key is reducing barriers: complicated application forms deter participation, while simple online portals or paper forms distributed at community centers invite broad engagement.

4. Evaluation and Feasibility Analysis: Budget analysts and technical staff assess proposals for cost, legality, and alignment with city priorities. This stage poses risks: if analysts overly filter or modify community ideas, PB devolves into "managed participation"—a Potemkin process that undermines genuine citizen input. Transparent criteria and community oversight of the evaluation phase protect against bureaucratic gatekeeping. Cities like Paris publish detailed feasibility reports for each proposal, allowing residents to understand why some ideas advance and others don't.

5. Voting: The democratic moment. Residents select winning projects through ranked-choice voting, approval voting (typically 5-7 projects per ballot), or knapsack voting (allocating a fixed number of tokens across projects within a budget constraint). Madrid's 2022 PB used knapsack voting with negative votes, allowing residents to both support favored projects and signal opposition to disfavored ones. Hybrid mechanisms—online portals, SMS voting, paper ballots at libraries and schools—maximize turnout while addressing the digital divide. Research in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, found that introducing online voting in 2015 increased total turnout by 8.2%, though it skewed toward younger, wealthier, more educated participants, underscoring the need for multi-modal access.

6. Implementation and Accountability: Governments execute winning projects and report back to residents. This final stage is critical for sustaining trust. When communities see their choices materialize—a renovated playground, a new community garden, upgraded school facilities—civic efficacy rises. Conversely, when bureaucratic delays or budget shortfalls derail approved projects, disillusionment sets in. Dashboard systems that track project timelines and spending transparency measures reinforce accountability.

Participatory budgeting doesn't merely redistribute money—it rewires civic relationships. In neighborhoods where PB operates, multiple transformations occur simultaneously:

Cognitive Shifts: Participants gain literacy in local governance and budgeting processes. A study in Rusafa, a low-income district in Baghdad, Iraq, documented increased knowledge about municipal operations and enhanced ability to analyze community needs among PB participants. When residents learn how budgets work, they become more sophisticated advocates and more discerning voters. Schools implementing participatory budgeting report that students develop deliberative capacities, decision-making power, and stronger school citizenship—skills that carry into adult civic life.

Social Capital Formation: PB creates networks and trust. When neighbors collaborate to prioritize projects, debate trade-offs, and mobilize votes, social bonds strengthen. Mixed-methods research shows that PB increases the number of civil-society organizations and fosters collaboration across organizations. People Powered's evidence synthesis—drawn from 70 scholarly articles and 34 case studies—documents that PB participation can transform individual attitudes, fostering greater tolerance and disposition to solve conflicts democratically.

Institutional Legitimacy: Governments that embrace PB often see enhanced credibility. Transparent budgeting builds trust: when citizens understand how public funds are allocated and spent, they're more likely to believe officials act responsibly. Research in municipalities with PB shows higher trust in local authorities compared to similar cities without PB. This legitimacy dividend is especially valuable in contexts of low institutional trust—66% of Americans feel special interests dominate government, according to a 2021 Public Agenda poll.

Economic Multipliers: Beyond direct project funding, PB can stimulate local economic activity. Infrastructure improvements—sidewalk repairs, park upgrades, street lighting—enhance property values and neighborhood vitality. Los Angeles's L.A. REPAIR allocated approximately $8.5 million across nine neighborhoods in 2021, funding job training, rental assistance, and medical services in areas where 87% of residents identify as BIPOC and at least 16% live below the poverty line. These investments address systemic inequities while creating economic opportunity.

Movement Building: PB serves as a civic gymnasium where grassroots organizers hone strategies and build coalitions. Jane DeRonne of the Participatory Budgeting Project describes "good PB" as intentionally centering people and organizations already working for social justice, holding governments accountable for shifting power. In Cleveland, the People's Budget campaign mobilized residents to pass a historic 2023 ballot initiative mandating 2% of the General Fund for PB annually, building on earlier advocacy for ARPA fund allocation. PB creates a connective tissue between reformers inside government and community organizers outside, fostering collaboration across traditional divides.

The case for participatory budgeting rests on both normative ideals and empirical outcomes. Normatively, PB embodies democratic theory's highest aspirations: direct citizen engagement, deliberative decision-making, and government responsiveness. It challenges the representative model's inherent limitations—elite capture, special interest influence, disconnect between officials and constituents—by creating a parallel governance structure grounded in popular sovereignty.

Empirically, PB delivers measurable benefits:

1. Redistributive Justice: PB tends to allocate resources toward low-income areas and underserved communities. Porto Alegre's Quality-of-Life Index explicitly weighted investments toward neighborhoods with the greatest need, narrowing gaps in infrastructure and services. Analysis of U.S. PB programs shows projects concentrated in education, workforce development, community assistance, and infrastructure improvements in marginalized neighborhoods. The distributional impact is real and sustained.

2. Fiscal Responsibility: Counter-intuitively, giving communities budget control often improves fiscal outcomes. The World Bank found that Brazilian municipalities with PB experienced significant revenue increases and reduced tax delinquency. When residents see tangible returns on their tax dollars, compliance rises. Moreover, PB projects tend toward cost-effectiveness: research using multi-agent reinforcement learning on real-world PB data from Aarau, Switzerland, and Toulouse, France, reveals that voters guided by AI decision support allocate resources more fairly when focusing on lower-cost projects. This suggests that choice architecture and voter education can optimize outcomes.

3. Democratic Renewal: PB revitalizes civic engagement in an era of widespread alienation. In Porto Alegre during the 1990s, protests, demonstrations, and land invasions dropped from over 30 per year to 10 following PB implementation, as residents channeled demands through institutionalized participation. While some critique this as co-optation, it also reflects successful conflict mediation and enhanced governmental responsiveness. In contexts where democracy feels performative, PB offers a mechanism for authentic voice and influence.

4. Innovation Incubation: PB encourages creative problem-solving. When diverse community members brainstorm projects, novel solutions emerge that professional planners might miss. A resident in Ghent proposed mobile green spaces that could rotate between neighborhoods; students in Edmonton suggested multi-use community hubs combining recreation and food security. PB democratizes innovation, valuing lived experience alongside technical expertise.

5. Scalability Across Contexts: PB adapts to wildly different settings. It functions in megacities like New York (population 8 million) and small towns like Asheville (population 95,000). It operates in wealthy European capitals and resource-constrained cities in the Global South. It's been embedded in schools, corporations (Scaled Agile Framework promotes participatory budgeting for enterprise portfolio management), and even business improvement districts. This flexibility stems from PB's modular design: the core principles—transparency, deliberation, direct decision-making—can be tailored to local contexts, cultures, and capacities.

No governance innovation is panacea. Participatory budgeting confronts persistent challenges that, if unaddressed, limit effectiveness or generate unintended harms:

1. The Digital Divide: E-participatory budgeting expands access but risks exacerbating inequality. Online voting platforms attract younger, wealthier, more educated participants with reliable internet access and digital literacy. In Rio Grande do Sul, online voters skewed male, younger, and more educated than traditional participants. Residents without smartphones or broadband—often seniors, low-income households, and rural communities—face exclusion. Unless cities provide multi-modal participation (paper ballots, telephone voting, public computer access), digital PB replicates existing disparities under a veneer of inclusivity.

2. Elite Capture and Managed Participation: Wealthier, better-organized groups can hijack PB processes to secure benefits for themselves. In the absence of safeguards—geographic fairness rules, ranked voting systems, point-based allocations—affluent neighborhoods mobilize higher turnout and secure disproportionate resources. Moreover, when budget analysts filter community proposals through bureaucratic criteria, "managed participation" emerges: residents nominally control decisions, but officials shape outcomes behind the scenes. Transparency in evaluation criteria and community oversight mitigate but don't eliminate this risk.

3. Voter Fatigue and Choice Overload: PB demands time, attention, and cognitive effort. Residents must learn about dozens of proposals, assess trade-offs, and cast informed votes. Research on the Aarau PB election (33 projects, 1,703 voters) highlights "choice overload"—too many options overwhelm voters, reducing decision quality. Streamlined ballot design, AI-powered recommendation tools, and curated shortlists can alleviate this burden, but they introduce new concerns about algorithmic bias and technocratic gatekeeping.

4. Political Resistance: Elected officials often view PB as a threat to their authority and discretion. Councilmembers accustomed to distributing capital funds as patronage resist processes that empower constituents directly. In Porto Alegre, a conservative coalition effectively gutted PB after 2004 by maintaining formal structures while shifting substantive power back to traditional elites. Political resistance manifests as bureaucratic delays, inadequate funding, selective implementation, or outright suspension. Overcoming this requires framing PB as enhancing transparency and accountability—tools that strengthen rather than undermine representative democracy—while building coalitions that include progressive officials and grassroots advocates.

5. Sustainability and Burnout: PB is resource-intensive. Edmonton's pilot consumed 300 staff hours over 4-5 months by 13 community services employees to allocate $69,000 across six projects—a ratio some cities deem unsustainable. Volunteer burnout threatens continuity: community organizers and budget delegates shoulder significant workloads without compensation. Long-term viability depends on integrating PB into regular municipal operations, providing stipends or recognition for participants, and scaling incrementally to build capacity without overwhelming stakeholders.

6. Bureaucratic and Budgetary Constraints: PB requires flexible capital budgets and administrative willingness to execute community decisions. In cities with rigid earmarks, debt obligations, or legal restrictions, the menu of fundable projects shrinks, limiting PB's scope. When approved projects face delays or cancellations due to cost overruns or regulatory hurdles, trust erodes. Legal mandates and transparent dashboards can enforce accountability, but they also require political will to establish and defend.

7. Unrepresentative Participation: Even with robust outreach, PB participants often skew toward more engaged, civically active residents. Low overall turnout—NYC's 76,434 votes in 2024 across a city of 8 million—raises questions about representativeness. If only 1-3% of residents participate, do outcomes reflect community priorities or the preferences of a mobilized minority? This challenge underscores the need for continuous outreach, varied engagement channels, and careful analysis of demographic participation patterns to identify and address gaps.

Participatory budgeting's global diffusion has produced fascinating variations shaped by local democratic traditions, governance structures, and cultural values:

Latin America: The birthplace of PB remains its most fertile ground. Beyond Porto Alegre, cities across Brazil, Argentina, Peru, and Uruguay have adopted PB, often embedding it within broader participatory governance frameworks. Latin American PB tends toward social movement alignment, explicitly redistributive goals, and integration with neighborhood associations. The region's experience offers lessons in both promise and peril: PB can drive transformative equity, but it's vulnerable to regime changes and political cycles.

Europe: Over 100 European cities had participatory budgets by 2008, with nearly 5 million residents involved. Yves Sintomer, Carsten Herzberg, and Anja Röcke identify six ideal-types of European PB: Porto Alegre adapted for Europe, representation of organized interests, community funds at local and city levels, public-private negotiating tables, consultation on public finances, and proximity participation. European PB often emphasizes consultation over binding decisions, operates at smaller scales (neighborhood rather than citywide), and integrates more closely with existing civil society structures. Political impacts tend to be more modest than in Latin America, with limited redistribution effects, reflecting Europe's stronger welfare states and different inequality patterns.

North America: The United States launched its first PB process in Chicago in 2009. Since then, over 50 U.S. cities have moved more than $400 million into community hands. American PB emphasizes accessibility (multi-language ballots, extended voting periods, youth participation) and legal codification (ballot initiatives, charter revisions). New York City's program is the largest, with 29 of 51 council members leading PB initiatives in 2024. However, American PB also faces unique challenges: federal funding cuts under hostile administrations threaten sustainability, and hyper-local implementations (district-by-district rather than citywide) create uneven access and quality.

Asia and Africa: PB adoption in these regions remains nascent but growing. Dhaka, Bangladesh, confronts fragmented governance across two city corporations, multiple ministries, and utility boards—96% of residents in a 2020 study were unaware of the city budget. Advocates propose ward-level PB allocating 1-2% of development funds through hybrid mechanisms (digital platforms, SMS voting, public assemblies) to clarify accountability and engage marginalized populations. Successful pilots at the union parishad level demonstrate feasibility. African cities, grappling with rapid urbanization and limited fiscal capacity, view PB as a tool for improving service delivery and fostering social cohesion, though implementation remains limited by institutional capacity and political stability.

International Cooperation and Competition: PB has become an arena for soft power and knowledge transfer. Organizations like People Powered, the Participatory Budgeting Project, and international bodies (World Bank, UN-Habitat, UNDP) promote PB as a governance best practice, offering training, toolkits, and technical assistance. This international advocacy facilitates diffusion but also risks imposing standardized models ill-suited to local contexts. Scholars caution against "PB fundamentalism"—the assumption that one-size-fits-all—and advocate for context-sensitive adaptation that respects local political cultures and governance capacities.

Whether you're a resident seeking to launch PB in your community, a municipal official exploring implementation, or a civic organizer scaling existing programs, several actionable strategies emerge from decades of global experience:

For Residents and Organizers:

1. Start Small and Build Evidence: Launch a pilot in a single neighborhood or ward with a modest budget ($50,000-$100,000). Document participation rates, project outcomes, and resident satisfaction meticulously. Use success stories to advocate for expansion. Newham's phased scaling from one neighborhood to multiple demonstrates the power of incremental growth.

2. Coalition-Building: Assemble diverse stakeholders—community organizations, schools, faith groups, business associations—to co-design the PB process. Broad coalitions lend legitimacy and mobilize turnout. Cleveland's People's Budget campaign exemplifies strategic coalition-building to pass ballot initiatives and secure funding.

3. Frame PB as Transparency, Not Threat: When engaging elected officials, emphasize that PB enhances accountability and strengthens representative democracy rather than replacing it. Officials retain oversight and can showcase responsiveness to constituents. Michael Cusack of the Participatory Budgeting Project advises framing PB as a tool for elected leaders to "double down on democracy" in an era of fiscal constraint and public skepticism.

4. Prioritize Equity from Day One: Design explicit equity frameworks addressing access (multi-language, multi-modal participation), fairness (geographic distribution rules, targeted outreach to marginalized groups), and quality (robust deliberation, transparent evaluation). The comparative analysis by Pape and Lerner identifies five equity challenges—facilitating inclusion, ensuring accessible processes, clarifying objectives, motivating participants, and overcoming budgetary constraints—each requiring intentional intervention.

5. Leverage Technology Wisely: Digital platforms reduce barriers and expand reach, but they must complement, not replace, in-person engagement. Hybrid models—online voting plus physical town halls, SMS updates paired with voicemail lines—address the digital divide. Invest in user-friendly interfaces, mobile optimization, and multilingual support. Asheville's multi-channel recovery engagement, achieving a 74.3% email open rate, illustrates effective digital-physical integration.

For Municipal Officials:

1. Allocate Adequate Resources: PB requires dedicated staff, outreach budgets, and technical support. Underfunded initiatives fail. Budget 1-2% of discretionary capital funds for PB projects and ensure staffing for coordination, evaluation, and implementation phases. Edmonton's experience—300 staff hours for a small pilot—highlights administrative costs that must be anticipated and resourced.

2. Legal Codification: Embed PB in municipal charters, ordinances, or voter-approved initiatives to insulate it from political whims. Cleveland's 2% General Fund mandate and New York's Charter Revision Commission guarantee sustainability beyond individual administrations. Legal frameworks also clarify roles, timelines, and accountability mechanisms.

3. Transparent Evaluation Criteria: Publish clear, objective criteria for assessing proposal feasibility. Explain why projects advance or are rejected. Invite community review of evaluation processes to prevent "managed participation." Paris's detailed feasibility reports serve as a model.

4. Invest in Capacity-Building: Train staff on facilitation, equity practices, and participatory governance. Engage residents through workshops on budgeting basics, project proposal writing, and deliberative dialogue. Treat PB as a long-term learning process for both government and community.

5. Monitor and Report Outcomes: Create public dashboards tracking approved projects from vote to completion. Report delays, budget adjustments, and challenges transparently. Celebrate successes and learn from setbacks. Trust grows when governments follow through and communicate honestly.

Skills to Develop:

• Deliberative Competence: The ability to weigh competing priorities, articulate preferences, and compromise constructively.

• Budget Literacy: Understanding revenue sources, capital vs. operating budgets, and fiscal constraints.

• Digital Fluency: Navigating online platforms while maintaining critical awareness of their limitations and biases.

• Organizing Capacity: Mobilizing neighbors, building coalitions, and sustaining engagement over months-long PB cycles.

• Policy Advocacy: Translating grassroots demands into policy proposals and navigating bureaucratic processes.

These skills transform residents into civic entrepreneurs—agents capable of shaping their environments through collective action. Schools implementing participatory budgeting cultivate these competencies in students, creating a pipeline of informed, engaged future citizens.

Participatory budgeting stands at a crossroads. After 35 years and adoption by over 11,500 institutions worldwide, PB has matured from Brazilian experiment to global governance tool. Yet its future is uncertain. Political pushback intensifies as elected officials recognize PB's power to redistribute authority. Federal funding cuts threaten U.S. programs. Digital divides risk creating two-tiered civic participation. And the sheer administrative burden strains municipal capacity.

Yet the need for PB grows more urgent. In an era of democratic backsliding, institutional distrust, and widening inequality, participatory budgeting offers something rare: a proven mechanism for ordinary people to exercise meaningful power over public resources. It's not a silver bullet—no governance tool is—but it's a practical step toward more responsive, equitable, and legitimate democracy.

The choice facing cities is straightforward: continue traditional budgeting, where elected officials and bureaucrats allocate funds with limited input and accountability, or embrace participatory processes that share power, build trust, and deliver measurable outcomes. The evidence from Porto Alegre to New York, from Newham to Helsinki, demonstrates that when communities control budgets, infrastructure improves, civic engagement rises, and democracy feels tangible rather than abstract.

For residents, the path forward is equally clear: demand participatory budgeting in your city. Join existing initiatives. Organize coalitions. Pass ballot measures. Volunteer as a budget delegate. Vote in PB elections. Participatory budgeting only works when people participate—and participation is both a right and a responsibility. The alternative is a politics of spectacle, where you watch democracy on screens rather than shape it in streets, town halls, and ballot boxes.

The next chapter of participatory budgeting will be written not by scholars or advocates but by millions of residents who decide that fiscal democracy isn't utopian fantasy but practical necessity. The tools exist. The evidence is robust. The question is whether communities and governments possess the political will to share power genuinely and sustainably. Democracy doesn't defend itself—citizens must claim it, budget by budget, project by project, vote by vote.

Recent breakthroughs in fusion technology—including 351,000-gauss magnetic fields, AI-driven plasma diagnostics, and net energy gain at the National Ignition Facility—are transforming fusion propulsion from science fiction to engineering frontier. Scientists now have a realistic pathway to accelerate spacecraft to 10% of light speed, enabling a 43-year journey to Alpha Centauri. While challenges remain in miniaturization, neutron management, and sustained operation, the physics barriers have ...

Epigenetic clocks measure DNA methylation patterns to calculate biological age, which predicts disease risk up to 30 years before symptoms appear. Landmark studies show that accelerated epigenetic aging forecasts cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and neurodegeneration with remarkable accuracy. Lifestyle interventions—Mediterranean diet, structured exercise, quality sleep, stress management—can measurably reverse biological aging, reducing epigenetic age by 1-2 years within months. Commercial ...

Data centers consumed 415 terawatt-hours of electricity in 2024 and will nearly double that by 2030, driven by AI's insatiable energy appetite. Despite tech giants' renewable pledges, actual emissions are up to 662% higher than reported due to accounting loopholes. A digital pollution tax—similar to Europe's carbon border tariff—could finally force the industry to invest in efficiency technologies like liquid cooling, waste heat recovery, and time-matched renewable power, transforming volunta...

Humans are hardwired to see invisible agents—gods, ghosts, conspiracies—thanks to the Hyperactive Agency Detection Device (HADD), an evolutionary survival mechanism that favored false alarms over fatal misses. This cognitive bias, rooted in brain regions like the temporoparietal junction and medial prefrontal cortex, generates religious beliefs, animistic worldviews, and conspiracy theories across all cultures. Understanding HADD doesn't eliminate belief, but it helps us recognize when our pa...

The bombardier beetle has perfected a chemical defense system that human engineers are still trying to replicate: a two-chamber micro-combustion engine that mixes hydroquinone and hydrogen peroxide to create explosive 100°C sprays at up to 500 pulses per second, aimed with 270-degree precision. This tiny insect's biochemical marvel is inspiring revolutionary technologies in aerospace propulsion, pharmaceutical delivery, and fire suppression. By 2030, beetle-inspired systems could position sat...

The U.S. faces a catastrophic care worker shortage driven by poverty-level wages, overwhelming burnout, and systemic undervaluation. With 99% of nursing homes hiring and 9.7 million openings projected by 2034, the crisis threatens patient safety, family stability, and economic productivity. Evidence-based solutions—wage reforms, streamlined training, technology integration, and policy enforcement—exist and work, but require sustained political will and cultural recognition that caregiving is ...

Every major AI model was trained on copyrighted text scraped without permission, triggering billion-dollar lawsuits and forcing a reckoning between innovation and creator rights. The future depends on finding balance between transformative AI development and fair compensation for the people whose work fuels it.