Ancient Archaea in Your Gut: Rewriting Human Biology

TL;DR: The polyvagal ladder translates neuroscience into a practical framework for treating trauma by mapping three nervous system states. Research shows promise for PTSD treatment, though evidence remains mixed and the approach has important limitations.

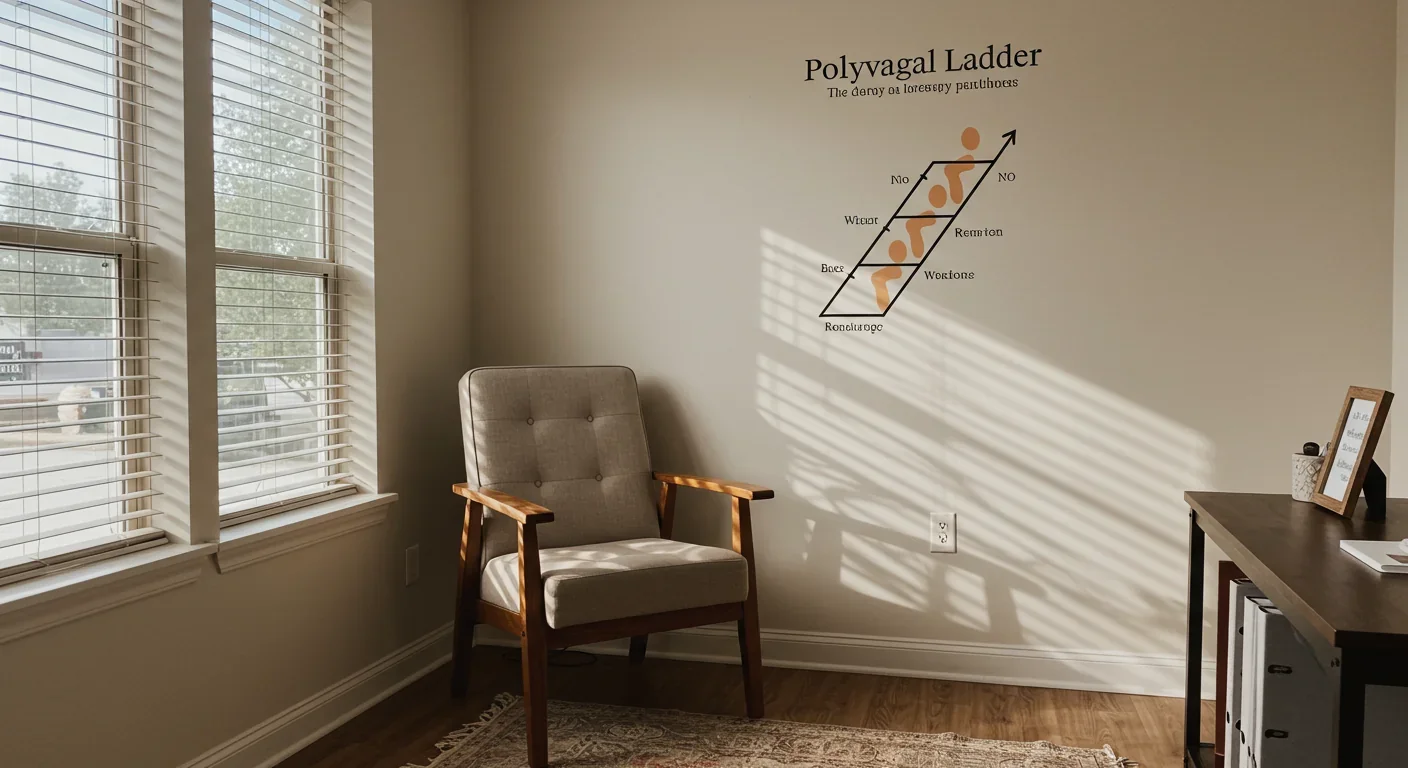

When Sarah's therapist first showed her the polyvagal ladder diagram, three ascending rungs representing different nervous system states, something clicked. For years, she'd blamed herself for freezing during stressful conversations or flying into rage over minor frustrations. The ladder revealed what her body had known all along: these weren't character flaws but predictable nervous system responses to perceived threat. Within six months of polyvagal-informed therapy, Sarah could recognize her position on the ladder in real-time and shift states deliberately, a transformation that traditional talk therapy alone hadn't achieved.

Stories like Sarah's are multiplying across therapy offices worldwide as clinicians adopt the polyvagal ladder framework, a clinical tool that translates complex neuroscience into an accessible map of human stress responses. But does this approach actually work, or is it just the latest therapeutic trend? The evidence reveals a framework grounded in solid neuroscience that's transforming trauma treatment, though questions about its limits remain.

The polyvagal ladder rests on Polyvagal Theory, introduced by Dr. Stephen Porges in 1994. Unlike earlier models that viewed the autonomic nervous system as a simple on-off switch between stress and calm, Porges identified three distinct neural circuits that evolved to help humans navigate safety and danger.

At the top of the ladder sits the ventral vagal state, controlled by the newest evolutionary branch of the vagus nerve, the longest cranial nerve that connects brain to body. When this system activates, you feel safe, socially engaged, and connected. Your heart rate variability increases, facial expressions soften, and you can think clearly while reading social cues accurately.

The middle rung represents the sympathetic nervous system, our mobilization response. When threats appear, this system floods the body with adrenaline and cortisol, preparing for fight or flight. Heart rate spikes, muscles tense, and the brain narrows its focus to survival. This response saved our ancestors from predators, and it still activates during modern threats, from job interviews to relationship conflicts.

The bottom rung is the dorsal vagal state, the most ancient survival strategy. When fighting or fleeing seems impossible, this primitive branch of the vagus nerve triggers shutdown: energy conservation, numbness, dissociation, and sometimes total collapse. It's the biological equivalent of playing dead, and for trauma survivors, it can become a default response to stress.

The ladder metaphor captures how nervous system responses follow a predictable hierarchy. You cannot leap from shutdown directly to social engagement—the system must climb through mobilization first, however briefly.

What makes the ladder metaphor powerful is how it captures the hierarchical nature of these responses. You can't leap from shutdown directly to social engagement. The nervous system must climb through mobilization first, however briefly. Understanding this sequence helps both therapists and clients recognize where they are and what steps will actually shift their state.

While Stephen Porges developed the underlying neuroscience, clinical psychologist Deb Dana created the ladder metaphor that transformed abstract theory into practical therapy. Dana recognized that trauma survivors needed more than scientific explanations. They needed a visual map that made sense of their confusing, often contradictory responses to stress.

The ladder works because it removes shame from the equation. When clients understand that freezing during conflict isn't weakness but an ancient survival mechanism, they stop fighting their own nervous systems. As one therapist explains, "It helps reduce shame and blame, as it educates clients on what is actually happening inside their body, and how the brain and body sends and receives information."

Polyvagal-informed therapy starts with helping clients identify their current state. What does your ventral vagal state feel like in your body? What physical sensations signal you're sliding into sympathetic activation? Learning to recognize these signs creates the foundation for intervention.

Therapists teach clients to track their "triggers" (events that push them down the ladder) and "glimmers" (moments of safety that pull them upward). A trigger might be a certain tone of voice that unconsciously signals danger. A glimmer could be sunlight on your face, a pet's warmth, or a friend's genuine smile, small experiences that tell your nervous system safety has returned.

The clinical applications extend far beyond simple awareness. Polyvagal therapy uses body-based techniques including breathing exercises, vocal toning, gentle movement, and what's called "co-regulation" where a calm therapist's regulated nervous system helps shift a dysregulated client's state. These aren't relaxation gimmicks but interventions targeting specific neural pathways.

Central to understanding the ladder is the concept of neuroception, the nervous system's continuous, unconscious scanning for safety or danger. Unlike perception, which involves conscious awareness, neuroception happens beneath conscious thought, constantly evaluating environmental cues through sensory input.

"Neuroception is the neural process by which safety and threat are detected without conscious awareness, driving autonomic state transitions."

— Dr. Stephen Porges, Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience

Your nervous system processes facial expressions, vocal tones, body language, and environmental features in milliseconds, deciding whether to activate social engagement, mobilization, or shutdown before you're consciously aware a decision has been made. This is why trauma survivors often react before they can think, why a certain smell or sound triggers intense responses that seem disproportionate to the actual threat.

For people with complex PTSD or developmental trauma, neuroception often becomes miscalibrated. Safe situations trigger danger responses. A colleague's neutral expression reads as hostile. A partner's normal stress response feels like abandonment. The nervous system, shaped by past experiences, sees threats everywhere.

Understanding neuroception explains why simply telling trauma survivors to "calm down" or "think rationally" doesn't work. You can't reason with a process that precedes conscious thought. Instead, effective intervention requires what Porges calls "neural exercises" that retrain the neuroceptive system to accurately distinguish safety from danger.

The polyvagal ladder proves especially valuable for treating complex PTSD, the persistent trauma that results from prolonged exposure to danger or chronic developmental trauma. Unlike single-event trauma, complex trauma fundamentally reshapes the nervous system's default settings.

Research shows that individuals with PTSD demonstrate reduced heart rate variability, a measure of vagal tone and nervous system flexibility. Lower HRV indicates a less flexible nervous system, one stuck in defensive states with limited capacity to return to social engagement.

The polyvagal framework reframes these symptoms not as disorders but as adaptations. A child raised in an unpredictable or dangerous environment develops a nervous system calibrated for threat, not safety. Hypervigilance, emotional reactivity, and dissociation made perfect sense in that context. The problem emerges when those protective strategies persist into adult life where they're no longer needed.

Treatment focuses on expanding what trauma therapists call the window of tolerance, the range of arousal where a person can function effectively without becoming dysregulated. For trauma survivors, this window often narrows to a sliver. Small stressors immediately push them into hyperarousal or hypoarousal.

The goal of polyvagal therapy isn't to stay in a calm state constantly, but to increase nervous system flexibility—moving fluidly through states as situations demand while reducing time stuck in defensive responses.

Polyvagal therapy gradually widens this window through carefully dosed experiences of safety. Clients learn to notice when they're approaching their window's edge and practice techniques to maintain regulation. Over time, the nervous system learns it can handle increasing amounts of activation without collapsing into defensive states.

The polyvagal ladder hasn't replaced other trauma treatments but enhanced them. Therapists increasingly integrate polyvagal principles with established approaches like EMDR, Internal Family Systems, and Somatic Experiencing.

Polyvagal-informed EMDR combines standard EMDR protocols with nervous system education and regulation techniques. Before processing traumatic memories through bilateral stimulation, therapists ensure clients have learned to recognize and shift autonomic states. This preparation helps prevent retraumatization and improves treatment outcomes.

Similarly, Somatic Experiencing practitioners use polyvagal concepts to explain why they focus on body sensations rather than trauma narratives. SE founder Peter Levine's work on the freeze response aligns closely with Porges' dorsal vagal state, and many SE therapists now explicitly teach the ladder framework.

Internal Family Systems therapists find polyvagal theory helps clients understand their "parts." Protective parts that hijack behavior often do so when the nervous system enters defensive states. Knowing your position on the ladder helps you communicate with these parts more effectively and create the safety needed for healing.

The common thread across these integrations is a shift from purely cognitive or narrative approaches to treatments that prioritize nervous system regulation. You can't process trauma effectively when your nervous system perceives ongoing threat. Establishing physiological safety comes first.

Understanding the ladder matters little without practical tools for shifting states. Fortunately, polyvagal-informed therapy offers numerous evidence-based techniques, many surprisingly simple.

Breathing exercises directly influence vagal tone. Slow, deep breathing with extended exhales activates the ventral vagal system. The key is breathing into your belly rather than chest, which signals safety to the nervous system. Exhaling for longer than you inhale specifically stimulates the vagal brake that slows heart rate and promotes calm.

Vocal techniques leverage the connection between the ventral vagus and muscles of the face and throat. Humming, singing, or even gargling stimulates vagal pathways. The Safe and Sound Protocol, developed by Porges himself, uses specially filtered music to exercise these neural pathways.

Movement helps discharge sympathetic activation. When you're in fight-or-flight, your body needs to complete the mobilization response. Walking, shaking, dancing, or any rhythmic movement helps metabolize stress hormones and shift from mobilization back toward social engagement.

Co-regulation remains one of the most powerful interventions. The human nervous system evolved to regulate through connection with other regulated nervous systems. Being in the presence of someone calm and safe, particularly when they engage facial expressions and voice, literally shifts your autonomic state. This explains why therapy works even when you don't talk about specific problems; the regulated presence of the therapist itself provides healing.

Environmental cues matter more than most people realize. Neuroception constantly scans for safety signals. Soft lighting, nature sounds, comfortable temperatures, and gentle textures all tell your nervous system you're safe. Conversely, harsh fluorescent lights, loud noises, and uncomfortable spaces trigger defensive states.

"The vagus nerve comprises a majority of afferent fibers that carry information from the body to the brain, supporting bottom-up regulation approaches."

— International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation

Grounding techniques help when you're in dorsal vagal shutdown. Rather than pushing yourself to "snap out of it," which rarely works, gentle physical sensations can coax the nervous system toward mobilization. Placing your feet firmly on the floor, pressing your hands together, or splashing cool water on your face provides sensory input that counters the numbness of shutdown.

The goal isn't to stay in ventral vagal state constantly, which would be impossible and undesirable. Healthy nervous systems move fluidly through all three states as situations demand. The difference polyvagal training makes is increasing flexibility and reducing the time stuck in defensive states.

Despite widespread clinical adoption, the scientific evidence for polyvagal interventions remains mixed, a distinction worth examining carefully. The underlying neuroscience of Polyvagal Theory is well-established, supported by decades of research on the autonomic nervous system and vagal function. Heart rate variability studies consistently show that trauma survivors have reduced vagal tone and that improving HRV correlates with better trauma outcomes.

However, specific polyvagal-informed therapeutic interventions need more rigorous study. Most evidence comes from case studies, clinical observations, and pilot programs rather than large randomized controlled trials. The research that exists shows promise but isn't yet definitive.

A 2024 review of vagal neuromodulation techniques, including HRV biofeedback and the Safe and Sound Protocol, found these approaches show potential for improving autonomic regulation and reducing anxiety, but larger studies are needed to establish effectiveness compared to standard treatments.

Research on heart rate variability in PTSD demonstrates that HRV predicts PTSD symptoms and treatment response, supporting the polyvagal framework's emphasis on vagal tone. Studies also confirm that trauma survivors with childhood abuse histories show more severe HRV deficits, suggesting early life experiences fundamentally shape autonomic functioning.

The mechanism research is stronger than the outcome research. We have solid evidence for how vagal interventions work, but need more studies comparing polyvagal therapy to other treatments on standardized outcome measures.

The mechanism research is stronger than the outcome research. We have solid evidence that vagus nerve stimulation affects mood and cognition, that co-regulation occurs through neural synchrony, and that body-based techniques influence autonomic state. What we need now are more studies directly comparing polyvagal-informed therapy to other trauma treatments on standardized outcome measures.

This doesn't mean the approach lacks value. Many effective therapies began with clinical observation and theoretical frameworks before rigorous research confirmed their benefits. CBT, EMDR, and countless medications followed this pattern. The polyvagal framework's clinical adoption suggests therapists find it useful, but science needs to catch up with practice.

No discussion of polyvagal therapy would be complete without acknowledging its critics and limitations. Some neuroscientists argue that Porges oversimplifies vagal anatomy and function, that the evidence for distinct ventral and dorsal vagal responses isn't as clear-cut as the theory suggests.

The ladder metaphor, while clinically useful, also risks oversimplification. Real nervous system function involves complex interactions between multiple systems, not just three discrete states. Some people don't fit the ladder model neatly, their responses blending states or following different patterns.

There's also concern about the commercialization of polyvagal therapy. The proliferation of certification programs, apps, and products claiming to be "polyvagal-informed" has outpaced the evidence. Not every technique marketed under the polyvagal banner actually targets the vagus nerve or autonomic nervous system in meaningful ways.

The framework works better for some conditions than others. While showing promise for PTSD, anxiety, and attachment issues, it's less clearly applicable to conditions like bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or OCD where other neural systems play primary roles. Trauma isn't the cause of every mental health condition, and polyvagal interventions aren't a universal solution.

Perhaps most importantly, focusing solely on nervous system regulation risks ignoring crucial factors like social inequality, ongoing trauma, lack of resources, and systemic oppression. You can teach someone to regulate their nervous system, but if they return to an abusive relationship or an exploitative job, the benefits are limited. Effective trauma treatment must address both physiology and environment.

Despite these limitations, the polyvagal framework represents an important shift in how we understand and treat trauma. By emphasizing the body's role in psychological healing, it validates what many trauma survivors intuitively knew: that healing requires more than talking or thinking differently.

The next decade will likely see more sophisticated applications of polyvagal principles. Wearable technology already tracks heart rate variability in real-time, potentially offering biofeedback to help people recognize and shift their autonomic state throughout daily life. Virtual reality therapy might create controlled environments for practicing ventral vagal activation before attempting similar states in real-world settings.

Integration with other neuroscience advances promises new possibilities. Understanding how the vagus nerve connects to inflammatory processes suggests polyvagal interventions might help with physical health conditions beyond mental health. Research on intergenerational trauma transmission indicates that improving parents' nervous system regulation could prevent trauma from passing to children.

"When clients understand that freezing during conflict isn't weakness but an ancient survival mechanism, they stop fighting their own nervous systems."

— Clinical observation from polyvagal-informed therapists

Most importantly, the polyvagal ladder gives both clinicians and clients a shared language for discussing experiences that were previously ineffable. When Sarah learned to tell her therapist "I'm in dorsal shutdown" or "I feel my sympathetic system activating," she gained agency over responses that had felt overwhelming and incomprehensible. That sense of understanding and control might be the framework's greatest contribution.

The ladder isn't a cure for trauma, and it won't work for everyone. But for many people struggling to understand why their body responds the way it does, why safety feels dangerous or why they can't "just relax," the polyvagal framework offers something precious: a map through terrain that had seemed impossible to navigate. As research continues and clinical practice evolves, that map will likely become more detailed, more accurate, and more helpful for the millions of people climbing their way back to safety.

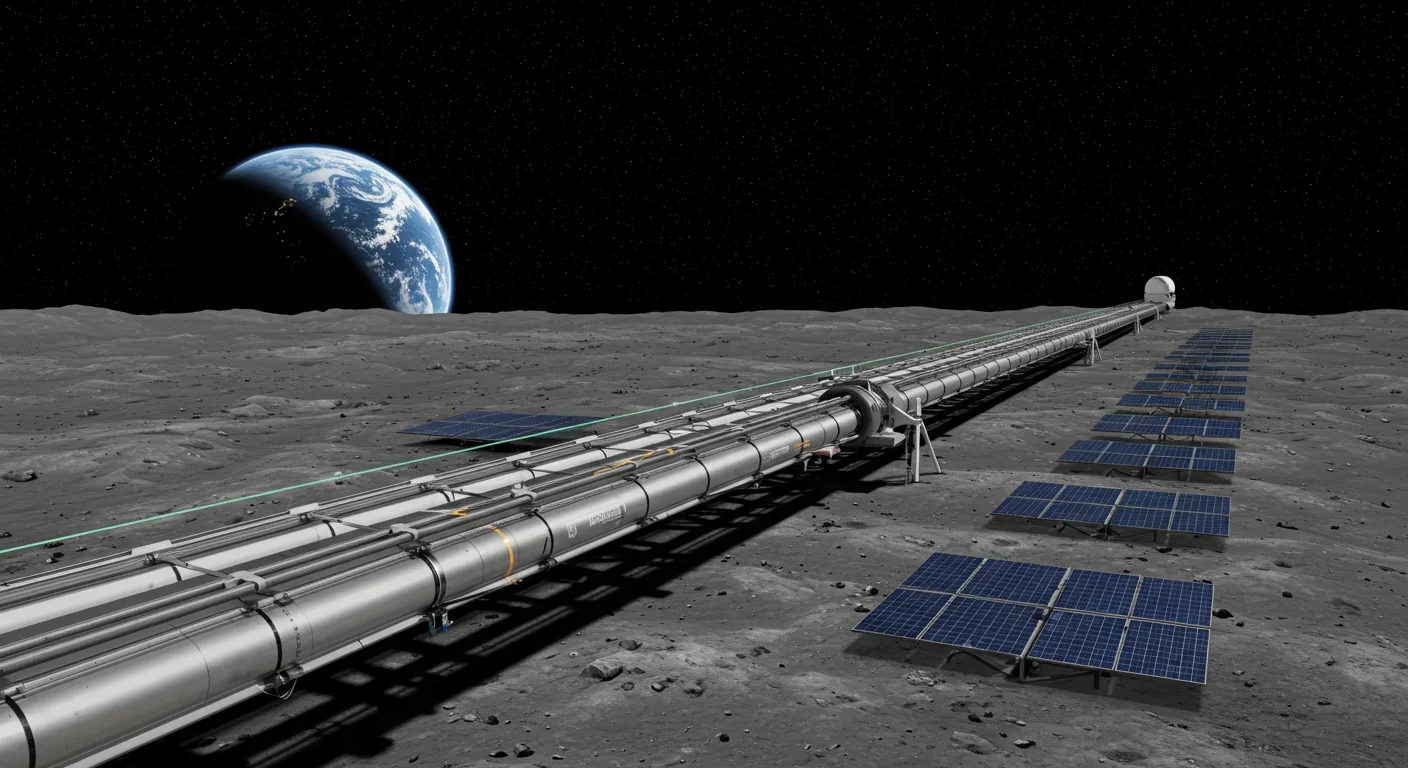

Lunar mass drivers—electromagnetic catapults that launch cargo from the Moon without fuel—could slash space transportation costs from thousands to under $100 per kilogram. This technology would enable affordable space construction, fuel depots, and deep space missions using lunar materials, potentially operational by the 2040s.

Ancient microorganisms called archaea inhabit your gut and perform unique metabolic functions that bacteria cannot, including methane production that enhances nutrient extraction. These primordial partners may influence longevity and offer new therapeutic targets.

CAES stores excess renewable energy by compressing air in underground caverns, then releases it through turbines during peak demand. New advanced adiabatic systems achieve 70%+ efficiency, making this decades-old technology suddenly competitive for long-duration grid storage.

Human children evolved to be raised by multiple caregivers—grandparents, siblings, and community members—not just two parents. Research shows alloparenting reduces parental burnout, improves child development, and is the biological norm across cultures.

Soft corals have weaponized their symbiotic algae to produce potent chemical defenses, creating compounds with revolutionary pharmaceutical potential while reshaping our understanding of marine ecosystems facing climate change.

Generation Z is the first cohort to come of age amid a polycrisis - interconnected global failures spanning climate, economy, democracy, and health. This cascading reality is fundamentally reshaping how young people think, plan their lives, and organize for change.

Zero-trust security eliminates implicit network trust by requiring continuous verification of every access request. Organizations are rapidly adopting this architecture to address cloud computing, remote work, and sophisticated threats that rendered perimeter defenses obsolete.