Cities Turn Social Media Into Public Service Powerhouses

TL;DR: Third places—cafés, libraries, pubs, and community centers where people gather outside home and work—are disappearing at alarming rates due to economic pressures, car-centric urban design, and digital isolation. This collapse drives a global loneliness epidemic killing 100 people hourly, erodes civic participation, and weakens local economies. Yet successful revitalization projects, policy reforms like mixed-use zoning and commercial rent stabilization, and grassroots initiatives demonstrate viable paths forward. Rebuilding third places isn't nostalgia—it's essential infrastructure for mental health, democracy, and social resilience in the 21st century.

Every day, 378 pubs close across Great Britain. Coffee shops fill with laptop workers who never speak. Libraries transform into silent coworking spaces. The neighborhood bar where your grandparents met friends has become a chain store. The bookstore where activists once gathered is now luxury condos. We're witnessing the systematic erasure of "third places"—those vital community hubs between home and work where democracy, mental health, and social capital are forged. The consequences reach far beyond nostalgia: loneliness now kills 100 people every hour globally, matching the mortality rate of smoking 15 cigarettes daily. As these gathering spaces vanish, we're conducting an unplanned experiment on human connection—and early results suggest we're losing something irreplaceable.

In 1989, sociologist Ray Oldenburg coined the term "third place" to describe the neutral public spaces where community life unfolds—distinct from home (first place) and work (second place). These are the cafés where regulars know your name, the libraries that host community meetings, the pubs that anchor neighborhoods, the barbershops that serve as informal town halls. Historic examples span millennia: Ancient Greek agoras hosted democratic discourse, Imperial Chinese teahouses facilitated business and politics, European coffeehouses earned the nickname "Penny Universities" for their accessible intellectual exchange.

Third places share defining characteristics: they're neutral ground where social status dissolves, conversation is the main activity, they're accessible and welcoming, regulars create a sense of belonging, the mood is playful, they cost little or nothing, and they serve as a home away from home. These aren't just pleasant amenities—they're infrastructure for social health.

The collapse is quantifiable. Independent U.S. bookstores dropped 40% from 1995 to 2000. African-American bookstores—critical hubs for civil rights organizing—declined from 250 to just 70 during the 1990s. British pubs, cornerstones of community life, fell below 39,000 in 2024 for the first time, with 412 demolished or converted that year alone. London lost 55 pubs in a single year. The pattern repeats globally: local coffee shops replaced by chain drive-throughs, community centers sold to developers, public squares redesigned to discourage gathering.

Meanwhile, one in six people worldwide experiences loneliness—a condition now linked to 871,000 deaths annually. In the United States, 33% of adults report feeling lonely, and 25% lack social and emotional support. The correlation isn't coincidental: Americans with no access to public or commercial community spaces are three times more likely to report having no close friends (32% versus 9%) than those with extensive access.

Multiple forces converge to eliminate community gathering spots. Economic pressures lead the assault. In the UK, pub operators face a £650 million annual cost increase from higher National Insurance contributions, rising minimum wages, and slashed business-rate relief—dropping from 75% to 40% in 2025. Energy bills remain double pre-Ukraine war levels. Card payment processing fees consume 1.5-3.5% per transaction, eroding already thin margins. The average pint now exceeds £5, forcing venues to choose between pricing out regulars or closing permanently.

Commercial rent follows a similar trajectory. High real estate costs drive small businesses toward rental properties, yet only 182 U.S. municipalities enforce rent-control regulations, concentrated in five states. Where rent control exists, it paradoxically tightens commercial supply—landlords convert vacant commercial units to higher-revenue residential spaces, reducing foot traffic opportunities. Independent bookstores, cafés, and community centers can't compete with chain retailers offering landlords guaranteed corporate leases.

Urban design compounds these pressures. Post-war suburbanization prioritized single-use zoning and car dependency. Job sprawl—45% of metropolitan employment now sits 10-35 miles from urban cores—forces long commutes that eliminate time for casual social stops. Parking minimums occupy land that could host mixed-use development. Wide arterial roads separate functions and make pedestrian activity dangerous. The result: neighborhoods where walking to a café or library is impractical or impossible.

Technological shifts deliver the final blow. Eighty percent of chain coffee houses now offer drive-through and mobile ordering, optimizing for speed over socialization. Remote work transforms cafés into silent laptop farms—the "alone together" phenomenon where physical proximity masks digital isolation. Social media provides a hollow substitute for face-to-face interaction; studies show digital and social media overuse, especially among young people, reduces real-life interactions and deepens isolation.

The third place collapse extracts steep tolls across multiple domains. Mental health impacts prove most immediate. A 2015 meta-analysis synthesizing data from 3.4 million participants found loneliness associated with a 26% increase in premature death risk, social isolation with 29%, and living alone with 32%. Loneliness increases risks of depression, anxiety, self-harm, stroke, heart disease, diabetes, and cognitive decline. The WHO Commission on Social Connection warns that lacking social connection poses health risks equivalent to smoking 15 cigarettes daily.

Rural communities face unique vulnerabilities. A Penn State study of 1,135 rural working-age adults found both attending third places and engaging with others there strongly associated with better mental health. Third place use represents a modifiable lifestyle factor for public health interventions—yet rural areas experience accelerating loss of gathering spots as small-town businesses close.

Civic participation suffers correspondingly. Third places historically hosted grassroots political organizing, from coffeehouses where revolutionaries plotted to bookstores where civil rights activists coordinated. The democratic function persists: neighborhoods with extensive civic infrastructure show residents far more likely to trust neighbors (39% versus 21%), engage in conversations, and participate in community decision-making. Conversely, communities with no civic access create "civic deserts" where residents lack both formal institutions and informal gathering spaces—21% of Americans live in such environments.

Educational disparities widen these gaps. College-educated Americans visit parks, libraries, and community centers far more frequently than non-degree holders (45% versus 27% visiting libraries at least a few times annually). This creates a feedback loop: those with fewer economic resources lose access to free public spaces that could provide social capital, information, and opportunity.

Economic consequences ripple through neighborhoods. Independent pubs contribute over £30 billion to the UK economy and support one million jobs. Their closure eliminates employment, reduces foot traffic for adjacent businesses, and decreases property values. Walkable neighborhoods with thriving third places demonstrate higher local business revenue, increased tourism appeal, and elevated real estate values. Studies using smartphone data of two million users found individuals moving to more walkable cities increased daily steps by 1,100—sustained over three months—with corresponding health cost savings.

Digital platforms present a paradox. Free Wi-Fi transforms libraries and coffee shops into productive work hubs, extending their utility. Remote work flexibility allows people to frequent third places during traditional office hours, potentially increasing usage. Libraries now offer digital literacy training, hotspot lending, and online resource access—bridging the digital divide for low-income populations.

Yet the same technologies hollow out social functions. The remote work boom means 25% of fully remote employees experience daily loneliness versus 16% of onsite workers. Older adults suffer disproportionately—nearly twice as likely as workers aged 16-24 to report social loss from remote work. The physical presence of bodies in cafés masks the reality of hundreds of isolated individuals in separate digital bubbles. As one café manager notes, customers increasingly occupy tables for hours without speaking to anyone.

Virtual "third places" emerge as potential substitutes. Online gaming communities, virtual worlds like Second Life, and digital collaboration platforms replicate some characteristics: regular participants, informal interaction, spontaneous bonding. Second Life's economy once eclipsed small countries, creating millionaire real estate entrepreneurs. Ethnographer Tom Boellstorff concluded such spaces constitute valid "places" where genuine human culture develops.

Yet crucial elements resist digitization. Ray Oldenburg insists: "Third places are face-to-face phenomena. The idea that electronic communication permits a virtual third place is misleading." Digital platforms lack spontaneity, serendipity, physical co-presence, and sensory richness. A 2007 study found employees at physical third places provide emotional support and companionship that algorithms cannot replicate. Virtual volunteering and online civic engagement, while valuable, fail to generate the neighborhood-scale trust and mutual aid networks that physical proximity enables.

Some venues intentionally design against digital isolation. Coffee shops designate laptop-free zones or limit Wi-Fi to encourage conversation. Libraries balance digital services with programming that brings people together: maker spaces with collaborative projects, storytelling corners that mix ages, community health services requiring face-to-face interaction.

Third place decline doesn't affect everyone equally. Low-income adults experience higher loneliness rates and reduced access to community spaces. Many third places require purchases—even a $5 coffee becomes prohibitive when budgets tighten. As one analysis notes, "third places are becoming a luxury," accessible only to those who can afford the entry fee.

Geographic disparities compound inequality. Urban cores retain more gathering spaces than suburbs, yet face gentrification pressures that displace affordable venues. Twenty-one percent of Americans live in civic deserts with zero or minimal public and commercial gathering spaces. Rural areas lose independent businesses to consolidation and population decline, leaving residents with neither traditional main street businesses nor suburban alternatives.

Age cohorts face distinct challenges. Young adults (18-24) report elevated loneliness despite digital connectivity—33% feel lonely, with rates higher still among low-income youth. They're growing up in a world where third places are scarce or commodified, lacking models for building face-to-face community. Older adults lose workplace social networks upon retirement, then find neighborhood third places have vanished. Fully 58% of American adults report loneliness, with peaks among both youngest and oldest cohorts.

Immigrants and marginalized groups historically relied on third places for community formation and mutual aid. African-American bookstores served as political organizing centers and cultural anchors; their near-disappearance removes crucial infrastructure. LGBTQ+ individuals, who often face family rejection, depend on affirming public spaces for support networks—yet gay bars, community centers, and welcoming cafés close at alarming rates.

International comparisons reveal divergent approaches. European cities typically maintain stronger café cultures and public square traditions. Zoning laws in many countries require mixed-use development, ensuring residential areas include commercial and community spaces. Vienna's coffee houses have survived centuries of political upheaval, protected as cultural institutions. Amsterdam prioritizes walkability and public space in urban planning, treating social infrastructure as seriously as transportation networks.

Asian cities demonstrate alternative models. Japan's dense urban fabric interweaves residential and commercial uses, with neighborhood ramen shops, bathhouses, and small parks serving third place functions. However, rapid modernization threatens traditional gathering spots. China's emphasis on large-scale development often demolishes historic hutongs (alleyway communities) and replaces them with separated-use superblocks that impede casual social interaction—despite high density, arterial roads create pedestrian barriers.

Developing nations face unique pressures. Rapid urbanization in African and Latin American cities creates sprawling informal settlements. While these areas generate organic third places—street markets, community churches, neighborhood associations—lack of formal infrastructure (safe water, reliable power, security) undermines their full potential. Yet informal third places often demonstrate greater inclusivity and democratic participation than formal Western institutions.

Some countries implement policy support explicitly. Porto Alegre, Brazil pioneered participatory budgeting in 1989, creating structured civic engagement that functions as a third place—regular public meetings where neighbors collaborate on community spending decisions. The model has spread globally; New York City's participatory budgeting engaged 18,000 residents allocating $14 million across diverse neighborhoods.

Despite bleak trends, revitalization efforts demonstrate what's possible. Independent bookstores staged a remarkable comeback—after a 40% decline from 1995-2000, numbers increased 35% from 2009-2015 as readers sought curated, community-oriented alternatives to online retail. These stores host author events functioning as literary salons, support local presses, and provide gathering space for reading groups and activists.

Libraries evolved beyond book repositories into dynamic community hubs. Nearly 90% now offer maker programming; 40% have production equipment like 3D printers and laser cutters. Kansas City Public Library provides health clinics, mental-health counseling, fitness classes, and food pantries—services requiring no insurance or qualifications. During emergencies, libraries serve as shelters, disaster response centers, and connectivity hubs. By expanding scope beyond books to address digital access, health, and social needs, libraries reclaim their role as the "last true public institution."

Urban planning innovations prioritize walkability and mixed-use development. High Line Park in New York transformed abandoned rail infrastructure into vibrant public space hosting millions of visitors. Cheonggyecheon Stream in Seoul removed a highway to restore a waterway and pedestrian area, catalyzing neighborhood revitalization. These projects demonstrate placemaking principles: community-driven design, inclusive programming, human scale, integration of nature.

Policy interventions show promise. Portland, Oregon's urban growth boundary limits sprawl, preserving density that supports third places. Cities adopting form-based codes over single-use zoning enable mixed-use neighborhoods where residents can walk to cafés, parks, and community centers. Jane Jacobs' advocacy for dense, mixed-use, walkable streets—once dismissed—now guides influential planning movements.

Participatory budgeting creates third place functions through process. Boston's first cycle collected 1,200 project ideas through 19 workshops, then had 4,462 residents vote on priorities. These gatherings foster neighbor-to-neighbor connections while directing public funds to community needs—including parks, libraries, and public space improvements.

Arizona's Crisis System reimagines emergency mental health care as third places. Rather than jails or emergency rooms, 24/7 stabilization centers provide professional observation and medication-assisted treatment in welcoming, dignified settings. Eighty-five percent of individuals remain stable weeks to months after engagement with mobile response teams or stabilization centers—outcomes far exceeding traditional emergency interventions. This illustrates how third place frameworks can extend beyond social gathering to address systemic care gaps.

Corporate adoption of internal third places represents another frontier. Ray Oldenburg notes surprise at business world uptake: "Managers found out that if they let people work where they want and when they want, productivity went up." Companies now design office cafés, informal gathering zones, and flexible spaces that mirror external third places—fostering cross-pollination, diversity of thought, and employee retention. Research shows actively engaged employees are 64% less likely to experience loneliness than disengaged peers, suggesting workplace social structures can partially compensate for external third place loss.

Individuals possess agency even within systemic constraints. Seek out and regularly patronize local third places—the independent café, neighborhood library, community center, or park. Consistency creates the "regular" status that anchors third place culture. Initiate conversations: ask a question, share an observation, acknowledge presence. Research shows even brief interactions with peripheral social network members enhance well-being.

For remote workers, intentionally work from third places at least one day weekly. Choose venues that welcome lingering—libraries, co-working spaces, cafés with community tables. Participate in programming: attend author readings at bookstores, join library maker spaces, volunteer at community gardens. These structured activities provide entry points for spontaneous social connection.

Create third places in unexpected locations. Ray Oldenburg converted his garage into a neighborhood bar, hosting regular Wednesday and Sunday gatherings with beer, wine, and diverse neighbors—a model requiring minimal investment. Organize recurring events: monthly potlucks, neighborhood walking groups, skills exchanges. The key is consistency—predictable timing allows community formation.

Advocacy amplifies individual actions. Attend city council meetings and advocate for mixed-use zoning, commercial rent stabilization, business rate reform for community venues, participatory budgeting, and public space investment. Join or form neighborhood associations that prioritize third place preservation. Support ballot initiatives that fund libraries, parks, and community centers. Vote for candidates committed to walkable development and anti-sprawl policies.

Community organizers can deploy the "Kind Challenge" intervention—a randomized controlled trial of 4,500 participants found that performing small acts of kindness for neighbors significantly reduced loneliness, stress, and neighbor conflict. Design programming that converts routine interactions into third place experiences: neighborhood beautification contests, community garden sharing circles, tool libraries, little free libraries that anchor blocks.

Businesses seeking to become third places should prioritize accessibility, welcome lingering, host events beyond commerce, maintain consistent hours, foster regular customers, employ friendly staff, and resist pressure for rapid turnover. Payment processing innovations—flat-fee models like Wonderful's One app charging £9.99/month for 1,000 transactions—can reduce costs that force rushed service.

Designers and developers must apply evidence-based guidelines: ensure accessibility through proximity and barrier-free entry, offer choice in seating and activity options, maintain human scale to feel welcoming, integrate nature for restorative benefits, create sense of place through local character, and activate spaces with programming that draws diverse users. These principles apply whether designing a public library, private café, or corporate office.

Governments hold powerful levers to reverse third place decline. Zoning reform stands paramount. Eliminate single-use zoning that separates residential, commercial, and public functions. Adopt mixed-use codes requiring ground-floor commercial in residential buildings. Reduce or eliminate parking minimums that consume land and prioritize cars over pedestrians. Implement form-based codes that prioritize walkability, street life, and human-scale development over separated-use sprawl.

Commercial rent stabilization protects existing third places. Only 182 U.S. municipalities regulate commercial rents—primarily in five states. Expand ordinances limiting rent increases and protecting small businesses from predatory leasing. Establish community land trusts that acquire property to lease affordably to community-serving businesses. Create business incubators providing below-market space for startups that serve neighborhood needs.

Business rate reform reduces operational pressures. The UK government's plan to introduce a permanent lower business rate from 2026 exemplifies necessary intervention—but implementation matters. Target relief specifically to independent community venues versus chain retailers. Consider graduated rates that favor smaller, locally-owned businesses over corporate operations.

Public investment in infrastructure makes third places viable. Fund library expansions incorporating maker spaces, community health services, and technology access. Invest in public squares, parks, and streetscape improvements that encourage lingering. Prioritize pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure over highway expansion. Studies show walkable infrastructure increases social interaction, reduces crime, and elevates property values—generating returns that offset initial costs.

Participatory budgeting institutionalizes democratic engagement while creating third place functions. New York City's model allocated $14 million across ten districts through public workshops and voting—engaging 18,000 residents, many from disenfranchised groups (youth, people of color, immigrants). Scale such programs citywide and dedicate portions specifically to third place creation and preservation.

Integrate social connection across policy domains. The WHO's SOCIAL Framework illustrates how health, transportation, housing, education, and leisure policies intersect to enable or impede social connection. Require social impact assessments for major developments: Will this project increase or decrease community gathering opportunities? Design transportation systems that facilitate casual social stops rather than just efficient commuting. Ensure housing policy includes community space requirements.

Support crisis care alternatives using third place frameworks. Arizona's model—24/7 stabilization centers providing dignified, professional mental health intervention—demonstrates superior outcomes to emergency rooms and jails. Fund similar initiatives nationwide, treating mental health infrastructure as essential social infrastructure.

The trajectory isn't predetermined. Current trends point toward accelerating loss: one British pub closes daily, remote work further isolates, chain consolidation continues, real estate costs rise. Without intervention, we face a future of profound disconnection—where community exists primarily online, where public space is fully commodified, where spontaneous human connection becomes rare and precious.

Yet counter-trends offer hope. The independent bookstore resurgence proves local, community-oriented alternatives can thrive when consumers choose them. Library reinvention shows public institutions can adapt to remain relevant. Participatory budgeting demonstrates appetite for meaningful civic engagement. The corporate embrace of internal third places suggests even profit-driven entities recognize social connection's value.

Technological developments cut both ways. Virtual worlds may provide supplementary gathering spaces—blockchain-enabled property rights and AI-assisted content creation could democratize virtual third place participation. Quantum computing might enable immersive experiences approaching physical world richness. Yet these will never fully replace embodied co-presence: the serendipitous hallway conversation, the barista who remembers your order, the stranger who becomes a friend.

Climate change adds urgency. As extreme weather increases, community resilience depends on social networks forged in third places. Heatwaves require cooling centers; libraries fill this role. Disasters demand mutual aid; neighbors who know each other respond faster. Third places aren't luxuries—they're survival infrastructure.

The post-pandemic landscape reveals which changes stick and which revert. Remote work persists—75% of workers would take pay cuts to maintain flexibility—but loneliness drives renewed appreciation for face-to-face contact. Hybrid models may optimize: remote work for focus, in-person collaboration in office third places, neighborhood third places for social connection.

Ultimately, the future depends on choices we make now. Do we prioritize short-term development profits or long-term community health? Do we zone for car convenience or human connection? Do we accept loneliness as inevitable or invest in gathering space infrastructure? Do we allow third places to become luxuries or defend them as public goods?

Ray Oldenburg insists: "Third places are the heart of a community's social vitality and the foundation of a functioning democracy." The evidence supports this claim. Societies with robust third places demonstrate better mental health, stronger civic participation, more resilient economies, and greater social trust. Those lacking such spaces suffer isolation, polarization, and democratic decay.

The vanishing third place represents more than nostalgia for neighborhood bars and corner stores. It signals the dismantling of infrastructure that makes us human—spaces where strangers become neighbors, where democracy happens daily, where loneliness loses its grip. Rebuilding these spaces, whether physical or hybrid, whether public or private, whether traditional or reimagined, constitutes essential work for the 21st century. Our collective mental health, democratic vitality, and social fabric depend on it. The question isn't whether we need third places—the evidence is overwhelming. The question is whether we'll summon the will to save them before the last ones vanish.

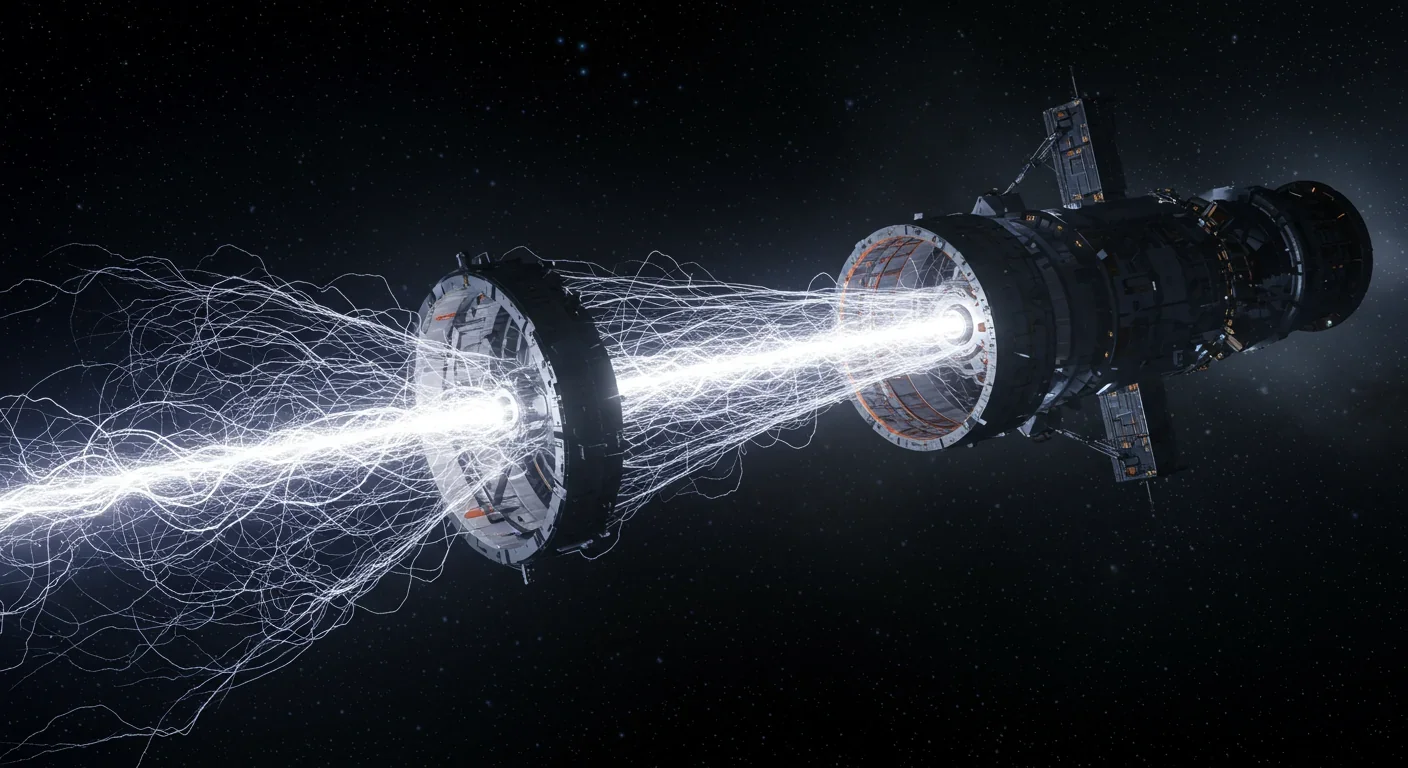

The Bussard Ramjet, proposed in 1960, would scoop interstellar hydrogen with a massive magnetic field to fuel fusion engines. Recent studies reveal fatal flaws: magnetic drag may exceed thrust, and proton fusion loses a billion times more energy than it generates.

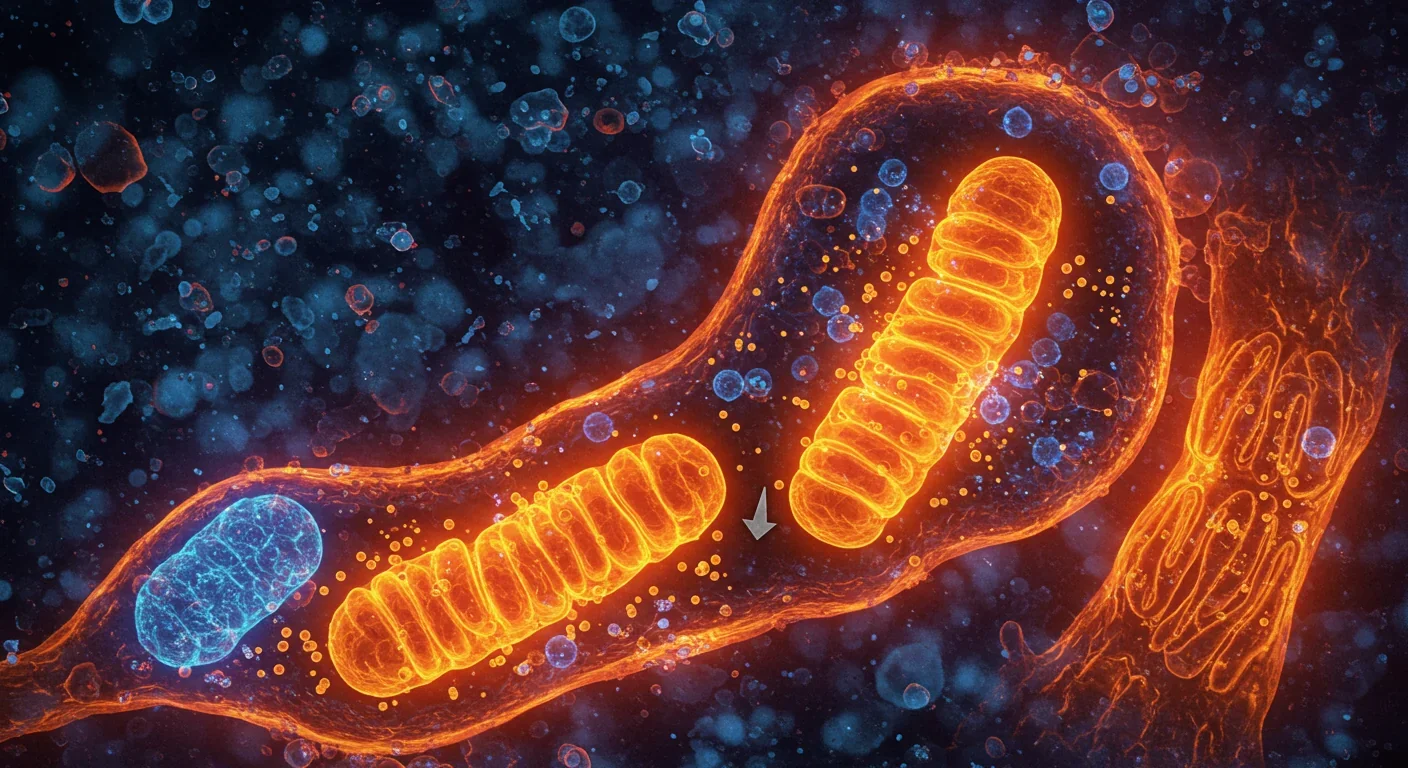

Mitophagy—your cells' cleanup mechanism for damaged mitochondria—holds the key to preventing Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, heart disease, and diabetes. Scientists have discovered you can boost this process through exercise, fasting, and specific compounds like spermidine and urolithin A.

Shifting baseline syndrome explains why each generation accepts environmental degradation as normal—what grandparents mourned, you take for granted. From Atlantic cod populations that crashed by 95% to Arctic ice shrinking by half since 1979, humans normalize loss because we anchor expectations to our childhood experiences. This amnesia weakens conservation policy and sets inadequate recovery targets. But tools exist to reset baselines: historical data, long-term monitoring, indigenous knowle...

Social media has created an 'authenticity paradox' where 5.07 billion users perform carefully curated spontaneity. Algorithms reward strategic vulnerability while psychological pressure to appear authentic causes creator burnout and mental health impacts across all users.

Scientists have decoded how geckos defy gravity using billions of nanoscale hairs that harness van der Waals forces—the same weak molecular attraction that now powers climbing robots on the ISS, medical adhesives for premature infants, and ice-gripping shoe soles. Twenty-five years after proving the mechanism, gecko-inspired technologies are quietly revolutionizing industries from space exploration to cancer therapy, though challenges in durability and scalability remain. The gecko's hierarch...

Cities worldwide are transforming governance through digital platforms, from Seoul's participatory budgeting to Barcelona's open-source legislation tools. While these innovations boost transparency and engagement, they also create new challenges around digital divides, misinformation, and privacy.

Every major AI model was trained on copyrighted text scraped without permission, triggering billion-dollar lawsuits and forcing a reckoning between innovation and creator rights. The future depends on finding balance between transformative AI development and fair compensation for the people whose work fuels it.