Cities Turn Social Media Into Public Service Powerhouses

TL;DR: Oakland schools cut suspensions by 31% using restorative justice circles that hold students accountable through conversation instead of punishment, dismantling the school-to-prison pipeline with proven results.

In 2009, Oakland Unified School District faced a troubling reality: Black students made up just 33% of enrollment but received 63% of all suspensions. A decade later, those numbers tell a completely different story. Suspensions dropped by 31%, and thousands of students who once would've been pushed out of classrooms are now sitting in circles, talking through their conflicts instead. What changed wasn't stricter rules or more security guards—it was a fundamental rethinking of what discipline actually means.

This shift from punishment to restoration is sweeping across American schools, and the data suggests it might be the intervention we've needed all along. Restorative justice practices are dismantling the school-to-prison pipeline one conversation at a time, replacing zero-tolerance policies with something far more effective: genuine accountability paired with community healing.

The school-to-prison pipeline isn't a metaphor. It's a documented pathway where disciplinary policies push students out of schools and into the juvenile justice system, particularly students of color and those with disabilities. Zero-tolerance policies, which gained momentum in the 1990s, created a culture where minor infractions could lead to suspensions, expulsions, and even arrests.

Research from the University of Chicago shows that stricter middle school discipline policies increased the risk of adult arrests for affected students. When schools remove students from learning environments, they don't just interrupt education—they set in motion a cascade of consequences that follow kids for years.

The disparities are stark. Students of color, especially Black students, face suspension rates two to three times higher than their white peers for identical behaviors. This isn't about differences in conduct. It's about how we perceive and respond to behavior, and the implicit biases baked into traditional discipline systems.

But here's where the story gets interesting: schools that adopted restorative justice practices saw those disparities begin to narrow. Not through ignoring misconduct, but by addressing it in ways that actually work.

Restorative justice in schools isn't soft on discipline—it's smarter about it. Instead of asking "What rule was broken and what's the punishment?" the approach asks "Who was harmed, what are their needs, and whose obligation is it to meet those needs?"

The framework typically operates on three tiers. Tier 1 focuses on building a trauma-informed school culture through community-building circles, where students and teachers regularly share experiences and build relationships. This isn't therapy—it's preventive infrastructure. When students feel connected to their school community, they're far less likely to cause harm in the first place.

Tier 2 responds to conflicts and incidents through restorative circles and conferences. When harm occurs, the people affected come together in a facilitated conversation. The student who caused harm hears directly from those impacted. Victims get to ask questions and express how they were affected. Together, the group develops a plan for repairing the harm and preventing future incidents.

Tier 3 provides intensive, individualized support for students facing the greatest challenges. This might include mentoring, counseling referrals, or ongoing restorative check-ins with dedicated staff.

Oakland's implementation shows what this looks like at scale. In a single school year, their program facilitated over 6,000 students through conflict circles, 3,000 through community-building circles, and 3,000 through one-on-one mediations. That's thousands of potential suspensions transformed into learning moments.

When Oakland schools assigned a restorative justice coordinator, suspensions dropped by approximately 20 percentage points within three years. Between 2015 and 2020, the overall suspension rate fell from 4.2% to 2.9%—nearly a third reduction across the district.

More importantly, teachers bought in. Surveys showed that 88% of Oakland teachers reported restorative practices were helpful in managing difficult student behavior. That's crucial, because reforms that make teachers' jobs harder don't last. Restorative justice gives educators tools that actually work, replacing frustration with frameworks.

The University of Chicago's analysis of Chicago Public Schools found similar results. Schools using restorative justice saw significant decreases in both suspensions and arrests, with particularly strong effects for reducing violent incidents. Students weren't getting away with misbehavior—they were being held accountable in ways that actually changed behavior rather than just removing them from sight.

Brookings Institution research confirms these patterns hold across different school contexts. The reduction in exclusionary discipline is consistent, and crucially, it doesn't come at the expense of school safety. In fact, many schools report improved safety as students develop conflict-resolution skills and feel more invested in their school community.

Implementation isn't as simple as declaring "we're doing restorative justice now." Oakland learned this the hard way. Their initial rollout happened quickly, driven by a federal agreement to address discriminatory discipline practices, and they didn't have time for school-level readiness assessments. Some schools thrived; others struggled.

The successful implementations share common elements. First, they start with buy-in at every level—from the school board to the principal to the teachers who'll actually facilitate circles. Policy frameworks matter: Oakland's school board passed a resolution formally adopting restorative justice, and the district incorporated RJ into official discipline matrices that guide administrator decisions.

Second, they invest in training. Not a one-day workshop, but sustained professional development that teaches teachers how to facilitate circles, manage difficult conversations, and recognize when restorative approaches are appropriate versus when traditional consequences are necessary. Some infractions—weapons, severe violence—still require removal, but restorative practices can complement even those interventions.

Third, successful programs dedicate specific staff time. Oakland assigned coordinators to schools, ensuring someone had bandwidth to organize circles, support teachers, and maintain the program. When restorative justice is just added to existing workloads without support, it fails.

Fourth, they engage families and communities. Parents need to understand why their child is sitting in a circle rather than facing suspension, and what accountability looks like in this model. Community support creates sustainability that outlasts budget cuts and leadership changes.

Let's be honest about the obstacles. Restorative justice requires significant upfront investment—in training, in staff time, in changing organizational culture. Districts facing budget constraints often struggle to justify those costs, even when long-term savings from reduced disciplinary processes are clear.

Time is another challenge. A restorative circle takes longer than writing up a suspension. Teachers already overwhelmed by demands on their time sometimes see RJ as one more thing added to their plates. That's why dedicated coordination and protected time for circles are essential.

There's also the learning curve. Facilitating restorative conversations is a skill that takes practice. Early attempts can feel awkward or ineffective. Some students initially see circles as a way to avoid consequences and test boundaries. It takes consistency and skill to make clear that accountability in a restorative model is actually more demanding than passive acceptance of a suspension.

Critics worry that restorative justice is too lenient, particularly for serious offenses. This concern often stems from misunderstanding: restorative practices don't replace all consequences. They offer an additional tool that addresses harm in ways punishment alone cannot. A student might face both a consequence and a restorative process. The key is ensuring the response actually repairs harm and changes behavior.

Cultural resistance runs deep. The punitive model is familiar; restoration requires trusting that something different can work. School leaders need patience and persistence to shift mindsets, backed by data showing what's happening in their own building.

States and districts can accelerate restorative justice adoption through several policy mechanisms. First, funding specifically earmarked for RJ implementation—covering training, coordinator positions, and ongoing support—makes the transition financially viable for more schools. California recently expanded funding for restorative justice programs, recognizing their effectiveness.

Second, discipline reform mandates can create the impetus for change. Oakland's transformation began with a Voluntary Resolution Process with the U.S. Department of Education to address discriminatory practices. External accountability, whether from federal civil rights enforcement or state legislation, pushes districts to seek alternatives to policies that disproportionately harm students of color.

Third, integrating restorative practices into teacher preparation programs ensures future educators enter classrooms with these skills from day one. Many current teachers learned discipline through the zero-tolerance lens and need significant retraining.

Fourth, data collection and reporting requirements help districts track whether restorative practices are working. Monitoring suspension rates, disciplinary disparities, student surveys on school climate, and academic outcomes creates accountability and identifies where additional support is needed.

The shift toward restorative justice reflects broader changes in how we understand human behavior and what actually promotes change. Decades of criminal justice research show that punishment alone doesn't reduce recidivism—it often increases it. Accountability paired with support and restoration works better.

Schools are microcosms of society, and the lessons from restorative justice extend beyond education. When we respond to harm by trying to understand its causes and repair its effects, rather than simply inflicting pain in return, we create conditions for actual behavioral change and community healing.

This matters particularly now, as polarization and isolation fragment communities. Restorative practices build connection in an era when many students lack stable communities. The circles teach skills—active listening, empathy, conflict resolution—that serve students throughout their lives.

The school-to-prison pipeline wasn't built in a day, and it won't be dismantled in one either. But every circle held, every suspension avoided, every student who stays in school rather than entering the justice system represents progress. Oakland's experience shows what's possible when we commit to something better.

For educators and administrators ready to explore restorative justice, start small. Don't try to transform everything overnight. Begin with community-building circles in a few classrooms. Train a core group of interested teachers who can model the practices and share what they learn.

Build relationships with existing restorative justice organizations and schools that have successful programs. Oakland worked with local RJ experts; many communities have practitioners who can provide training and support. National organizations like the International Institute for Restorative Practices offer resources and certification.

Measure what matters. Track suspension rates, but also survey students and teachers about school climate. Document the number of circles held and their outcomes. Share success stories—both data and narratives—to build support and demonstrate impact.

Be patient with the process. Culture change takes time, typically three to five years before practices become fully embedded. Early stumbles are learning opportunities, not reasons to abandon the approach.

Most importantly, remember that restorative justice isn't about being nice to kids who misbehave. It's about being effective. It's about creating school environments where all students can learn, where conflicts become teaching moments rather than exit ramps, and where accountability means truly addressing harm rather than simply inflicting punishment.

The school-to-prison pipeline exists because we built it through policies and practices that seemed logical at the time. We can dismantle it the same way—one policy change, one trained teacher, one restorative circle at a time. The evidence is clear. The tools are available. What's needed now is the will to commit to something that works better than what we've been doing.

Oakland's students aren't sitting in circles because the district went soft on discipline. They're sitting in circles because someone finally got serious about actually changing behavior and building community. That's not overcorrection—it's evolution. And it's working.

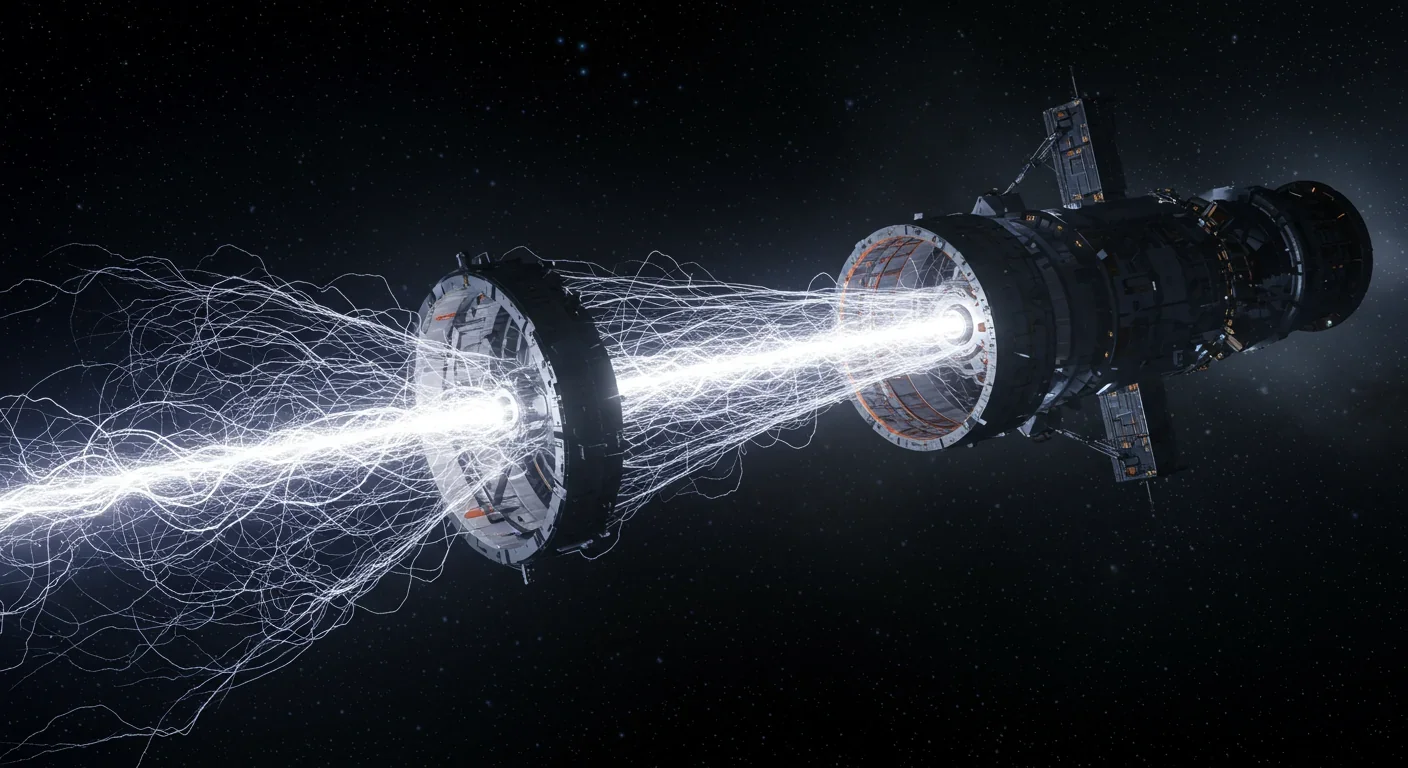

The Bussard Ramjet, proposed in 1960, would scoop interstellar hydrogen with a massive magnetic field to fuel fusion engines. Recent studies reveal fatal flaws: magnetic drag may exceed thrust, and proton fusion loses a billion times more energy than it generates.

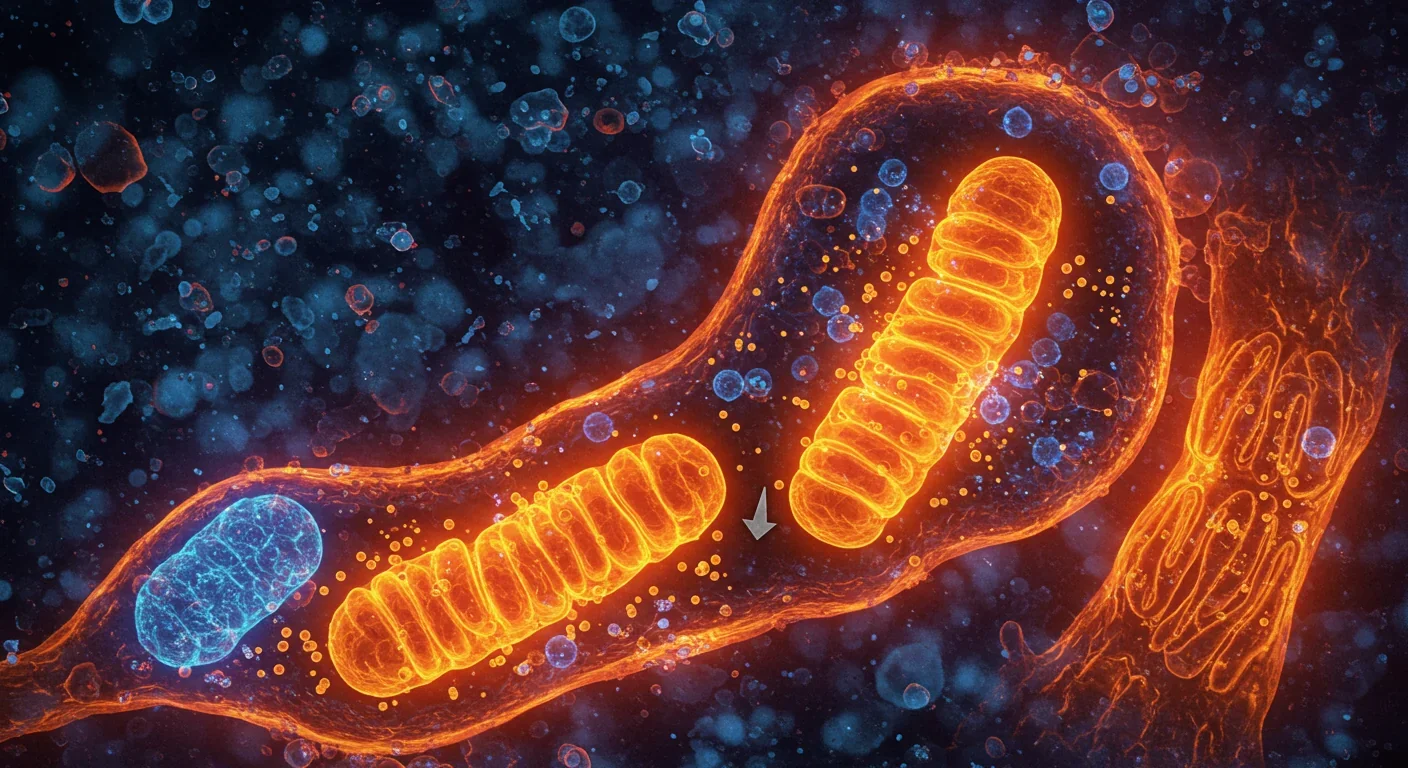

Mitophagy—your cells' cleanup mechanism for damaged mitochondria—holds the key to preventing Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, heart disease, and diabetes. Scientists have discovered you can boost this process through exercise, fasting, and specific compounds like spermidine and urolithin A.

Shifting baseline syndrome explains why each generation accepts environmental degradation as normal—what grandparents mourned, you take for granted. From Atlantic cod populations that crashed by 95% to Arctic ice shrinking by half since 1979, humans normalize loss because we anchor expectations to our childhood experiences. This amnesia weakens conservation policy and sets inadequate recovery targets. But tools exist to reset baselines: historical data, long-term monitoring, indigenous knowle...

Social media has created an 'authenticity paradox' where 5.07 billion users perform carefully curated spontaneity. Algorithms reward strategic vulnerability while psychological pressure to appear authentic causes creator burnout and mental health impacts across all users.

Scientists have decoded how geckos defy gravity using billions of nanoscale hairs that harness van der Waals forces—the same weak molecular attraction that now powers climbing robots on the ISS, medical adhesives for premature infants, and ice-gripping shoe soles. Twenty-five years after proving the mechanism, gecko-inspired technologies are quietly revolutionizing industries from space exploration to cancer therapy, though challenges in durability and scalability remain. The gecko's hierarch...

Cities worldwide are transforming governance through digital platforms, from Seoul's participatory budgeting to Barcelona's open-source legislation tools. While these innovations boost transparency and engagement, they also create new challenges around digital divides, misinformation, and privacy.

Every major AI model was trained on copyrighted text scraped without permission, triggering billion-dollar lawsuits and forcing a reckoning between innovation and creator rights. The future depends on finding balance between transformative AI development and fair compensation for the people whose work fuels it.