Cities Turn Social Media Into Public Service Powerhouses

TL;DR: Ancient Athens used lottery selection for government positions for 200 years, and this "sortition" model is experiencing a global renaissance. From Porto Alegre's participatory budgeting to Ireland's constitutional reforms, randomly selected citizens' assemblies are producing policy breakthroughs that elected bodies can't achieve. By eliminating money in politics, reducing polarization, and preventing elite capture, sortition offers a radically democratic alternative—or complement—to elections. The future of democracy might lie not in perfecting elections, but in rediscovering the lottery.

Imagine waking up to a notification: "Congratulations, you've been selected to serve in Congress." Not elected—selected. By lottery. Like jury duty, but for running the country. Sound absurd? Ancient Athens used this exact system for 200 years, and it's making a comeback in cities across the globe. As faith in elections crumbles under the weight of money, polarization, and elite capture, a radical idea is gaining traction: what if we chose our leaders the same way we pick lottery winners?

In the ruins of the Athenian Agora, archaeologists discovered something remarkable: the kleroterion, a stone slab riddled with slots arranged in precise columns. This wasn't art—it was democracy's original randomizer. Citizens would insert their tokens into slots, then an official would drop black and white dice down a tube. White dice meant your row got selected for public office. Black meant try again next year.

For two centuries, Athens filled most government positions this way. The Council of 500, which drafted all legislation? Chosen by lot. The 6,000-member jury pool? Random selection. Even most magistrates—roughly 600 of the 700 annual positions—were picked from a hat (or rather, a kleroterion). Only roles requiring specialized expertise—military generals and financial officers—were elected.

The logic was elegant: elections favor the wealthy, charismatic, and well-connected. Lotteries favor everyone equally. As Aristotle observed, "It is accepted as democratic when public offices are allocated by lot; and as oligarchic when they are filled by election."

The system worked because of built-in safeguards. You had to volunteer to enter the lottery (no one was drafted against their will). You faced a public scrutiny called dokimasia before taking office—a vetting process that could reject unsuitable candidates. You could only serve once or twice in your lifetime. And if you screwed up? The Assembly could remove you by popular vote, and you'd face a mandatory financial audit at the end of your term.

These weren't just theoretical protections. Athens introduced ostracism—a reverse lottery where citizens could vote to exile someone for ten years if they posed a threat to democracy. It required 6,000 votes to be valid, ensuring it wasn't used frivolously. When attempted in 416 BCE to resolve a power struggle between Alcibiades and Nicias, the two politicians conspired to exile a third person instead, revealing both the system's vulnerability and the lengths elites would go to game it.

Fast forward to 1989. Porto Alegre, Brazil faced a crisis: one-third of its population lived in impoverished favelas with no running water or sewers. The newly elected Workers' Party tried something unprecedented—participatory budgeting. Citizens gathered in community assemblies to debate spending priorities, then delegates (many chosen randomly) negotiated the final budget.

The results were stunning. By 2008, treated water reached 99% of the population. Sewer coverage jumped from 46% to 86%. Infant mortality dropped. School enrollment soared. Within two decades, over 120 Brazilian cities adopted the model. Today, roughly 11,000 cities, states, and institutions worldwide use some form of participatory budgeting.

But the most dramatic modern experiments came from Europe. In 2011, Belgium's government collapsed into a 541-day stalemate—the longest in modern democratic history. Frustrated citizens organized the G1000: a summit of 704 randomly selected Belgians who met to debate the nation's future. They discussed social security, wealth distribution, and immigration—topics politicians couldn't touch. A smaller panel of 32 citizens (the G32) distilled the summit's ideas into concrete recommendations and presented them to parliament on November 11, 2012.

Ireland went further. Between 2012 and 2014, the Constitutional Convention brought together 100 people—66 chosen by lottery, 33 nominated experts, and a chairperson—to debate constitutional reforms. When the Citizens' Assembly reconvened from 2016 to 2018, 99 randomly selected citizens tackled abortion, climate change, and aging. Their recommendation to repeal the Eighth Amendment (banning abortion) went to referendum and passed, becoming the 37th Amendment.

The Scottish Government responded officially to every recommendation from Scotland's Climate Assembly by December 16, 2021. The UK Climate Assembly—108 people selected to mirror the nation's demographics—delivered a 550-page report in September 2020 outlining how Britain could reach net-zero emissions by 2050. Members deliberately included people "not at all concerned" about climate change. By the end, they'd reached consensus on radical measures: frequent flyer taxes, meat consumption reductions, and rapid electric vehicle mandates.

The OECD has documented 733 citizens' assemblies between 1979 and 2023, with growth accelerating after 2010. These aren't fringe experiments—they're becoming standard tools for governments worldwide.

The process sounds simple but requires careful design. First, organizers send random invitations to tens of thousands of people—30,000 in the UK Climate Assembly's case. About 1,500 respond. From this pool, a second lottery selects the final group using stratified sampling to ensure representation across age, gender, ethnicity, education, geography, and relevant attitudes (like climate concern).

Selected members receive compensation—typically $100 per hour or equivalent—so participation doesn't privilege the wealthy. The UK's assembly cost £520,000 (about €2.4 million). Ireland's Citizens' Assembly cost €2,355,557 by March 2019. A European Citizens' Panel runs roughly €2 million for 150 participants across three weekends.

Once assembled, members enter a structured deliberative process:

Phase 1: Learning (2-4 weeks)

Experts present balanced information. For climate assemblies, this meant climate scientists, economists, engineers, and industry representatives. Members ask questions, review written submissions, and access additional materials.

Phase 2: Deliberation (4-8 weeks)

Members split into small groups with professional facilitators. Groups rotate regularly to prevent echo chambers. Discussions are livestreamed for transparency. Members debate trade-offs, challenge assumptions, and develop nuanced positions.

Phase 3: Decision-making (1-2 weeks)

The group votes on recommendations. Unlike elections, the goal isn't majority rule but informed consensus. Final reports detail not just what members decided but why—including minority positions.

Phase 4: Accountability

Governments are legally required to respond to recommendations. Ireland's government must answer in the Oireachtas (parliament). Scotland's government issued official responses to all Climate Assembly recommendations. This doesn't guarantee adoption, but it ensures assemblies aren't ignored.

The deliberative element is crucial. Studies show that when randomly selected citizens receive expert briefing and facilitated discussion, they outperform both uninformed public opinion and narrowly selected expert panels. A 2019 review in Science found that deliberation reduces polarization, counteracts populism, and produces more considered judgment—even among highly partisan participants.

1. Sortition Breaks Elite Capture

Competitive elections systematically favor candidates with time, money, connections, and name recognition. This produces legislatures dominated by the wealthy, educated, and socially elite. In the US Congress, over half of members are millionaires. In the UK Parliament, 29% attended private schools, though only 7% of the population does.

Random selection is statistically immune to elite capture. If you draw a representative sample, you get truck drivers, teachers, nurses, retirees, and yes, some lawyers and business owners—in proportion to their actual presence in society. No candidate can buy their way into a lottery. No political party can gerrymander the draw. No special interest can fund a campaign.

The Athenian example proves the point. Because all male citizens were eligible for sortition, leadership roles circulated through the widest possible cross-section of society. Wealthy aristocrats couldn't monopolize power. The system's rotation—no one could serve more than twice in a lifetime—prevented the emergence of career politicians.

2. Lotteries Eliminate Money in Politics

The 2020 US presidential election cost $14 billion. Candidates spend more time fundraising than governing. Donors gain access. Policy tilts toward those who can afford lobbyists.

Sortition eliminates all of this. There are no campaigns to fund. No attack ads to buy. No donors to reward. Assembly members serve temporarily—typically 6-18 months—then return to their regular lives. Lobbyists can't cultivate relationships with representatives who might not be there next year. The threat of future accountability (members can be randomly selected again) deters corruption.

Extinction Rebellion UK notes that assembly members are "less likely to be influenced by lobbyists because an assembly is temporary and made up of randomly selected members."

3. Random Selection Reduces Polarization

Elections incentivize polarization. Primary voters are more extreme than general election voters, pulling candidates toward the poles. Once elected, politicians face re-election pressures that reward partisanship over compromise. Media coverage amplifies conflict.

Citizens' assemblies operate differently. Members aren't representing party positions—they're tasked with solving a specific problem. Facilitators ensure all voices are heard. Rotation of small groups prevents faction formation. The result, repeatedly documented, is that "the group becomes less extreme."

An American experiment called "America in One Room" brought 500 nationally representative participants together for deliberation. Positive feelings toward the other political side increased 13 points. Support for online voter registration among Republicans jumped from 30% to 100% after hearing the arguments.

The UK Climate Assembly included climate skeptics. By the end, consensus emerged on policies that would have been politically impossible through normal channels.

4. Cognitive Diversity Beats Expertise

Political scientist Hélène Landemore argues that "the diversity of the members of an assembly is a strength for deliberation." Her research shows that random assemblies often outperform expert panels because they bring a wider range of perspectives, life experiences, and problem-solving approaches.

This isn't anti-intellectual. Assemblies include experts—but as advisors, not decision-makers. The Hong-Page "diversity trumps ability theorem" demonstrates mathematically that a cognitively diverse group of problem-solvers can outperform a homogeneous group of high-ability experts.

In practice, this means a climate assembly might include a farmer who understands land use, a factory worker who knows manufacturing constraints, a parent concerned about children's futures, and a retiree with historical perspective—alongside expert testimony. The combination produces richer, more implementable solutions.

5. It's More Efficient Than Referendums

Consider the social cost of decision-making. A referendum with 1 million voters, where each spends one hour understanding the issue, costs society 1 million hours of productivity—roughly $15 million at average wages. And most voters don't spend that hour; they vote based on headlines, party cues, or gut feelings.

A 500-member sortition assembly, where members deliberate for 160 hours over four weeks, costs 80,000 hours—but those hours are compensated at $100/hour (to ensure participation across income levels), totaling $8 million. The assembly produces an informed decision after extensive deliberation, at roughly half the social cost of getting voters to spend even one hour on the issue.

This calculation ignores quality. Jason Brennan's research suggests most voters are "hobbits" (indifferent and uninformed) or "hooligans" (passionate but irrational), with few "vulcans" (knowledgeable and balanced). Sortition with deliberation reliably produces vulcans.

The Competence Objection

The most common criticism: "You want random people making complex decisions?" Thomas Aitken frames it bluntly: "At face value, the idea that we should be ruled by random people, who likely don't have any relevant skills or knowledge, is the definition of an unserious position."

The response has three parts:

First, Athens already answered this. They combined lottery with dokimasia (vetting), term limits, and accountability mechanisms. Modern assemblies add structured learning phases, expert panels, and professional facilitation.

Second, elections don't guarantee competence. Voters often lack the knowledge to evaluate candidates' expertise. Campaign skills (charisma, fundraising, messaging) don't correlate with governing ability. Many elected officials have no relevant experience before taking office.

Third, the question assumes individuals govern alone. But both Athens and modern assemblies use collective deliberation. A single randomly selected person might be unqualified, but 500 randomly selected people, given time and resources to learn, reliably produce informed judgment.

Still, safeguards matter. Proposals for "epistocratic demarchy" suggest adding competency filters: security clearances for sensitive roles, probationary periods, specialized oversight committees. The Athenian hybrid model—elections for positions requiring expertise (generals, treasurers), lottery for others—offers another solution.

The Legitimacy Problem

Why should unelected citizens have authority? Democratic theory traditionally grounds legitimacy in consent—and elections are how we express consent.

But this argument cuts both ways. Low voter turnout, gerrymandering, and campaign finance corruption undermine electoral legitimacy. If only 50% of eligible voters participate, and the winner gets 51% of that vote, they represent 25.5% of the electorate.

Sortition offers a different legitimacy claim: descriptive representation. A properly selected assembly literally is the people, in miniature. The UK Climate Assembly's 108 members mirrored the population's demographics and attitudes—including climate deniers.

Moreover, lottery satisfies procedural fairness. As political philosopher David Estlund notes, a coin flip gives equal weight to all citizens' preferences, just like majority rule. The difference is epistemic: we prefer democracy to random chance because we expect it to make better decisions. But if sortition with deliberation makes better decisions than elections, the epistemic argument supports lotteries.

Public perception remains a hurdle. Irish assemblies enjoy high public awareness after multiple successful iterations. But Scotland's Climate Assembly and the UK People's Plan for Nature faced "insufficient publicity," limiting public pressure on policymakers. Legitimacy requires visibility.

The Participation Challenge

Lottery winners aren't obliged to participate. Response rates to initial invitations hover around 5%. This creates two problems:

First, self-selection bias. People who volunteer for assemblies might differ systematically from those who decline—perhaps more educated, politically engaged, or ideologically aligned with the topic.

Stratified sampling in the second-stage lottery mitigates this somewhat. The UK Climate Assembly reserved seats for participants from deprived postcodes. Ireland's Citizens' Assembly balanced for social class. But if certain demographics consistently refuse participation, representation suffers.

Second, resource constraints. Meaningful participation requires time off work, childcare, possibly travel. Compensation helps, but someone working multiple jobs or caring for elderly parents faces barriers beyond money. Porto Alegre's participatory budgeting addressed this through extensive outreach: translation services for non-English speakers, pop-up sites at homeless shelters, sessions in prisons. DemocracyNext's Cities Programme includes nine learning modules on inclusive recruitment.

Without deliberate effort, "random" selection risks reproducing existing inequalities.

The Implementation Gap

Even successful assemblies face a final hurdle: adoption. Citizens make recommendations; governments decide whether to implement them.

Ireland provides the success story. The assembly's abortion recommendation went to referendum and became constitutional law. Same-sex marriage followed a similar path. The government was legally required to respond to every recommendation, creating political pressure.

But France's first climate assembly saw many recommendations ignored or watered down, leading to "demoralization and loss of interest," as Brett Hennig notes. Scotland responded to all Climate Assembly recommendations—but responding doesn't mean acting.

Critics like Eoin O'Malley warn that assemblies become "a part of the policymaking system that supports the various agendas of lobby groups." Select the right experts, frame questions carefully, and you can steer outcomes while maintaining a veneer of citizen input.

This risk is real. The Conservative Woman's critique of UK assemblies notes that "lottery winners are not obliged to participate, and anyone with the wrong attitudes will find that their face doesn't fit." Independence matters. Ireland's assembly was run by independent organizations. The Belgian G1000 was "entirely designed and implemented 'by and for citizens', without governmental involvement."

In September 2025, something unprecedented happened on Discord. Over 10,000 young Nepalis—joined by 6,000 watching via YouTube livestream—used the gaming platform to select an interim prime minister through debate and voting.

The context: Nepal's government had collapsed amid protests. Discord had been banned earlier but was reinstated. Gen Z activists organized a virtual assembly with expert panels, fact-checking rooms, and anonymous participation. After hours of deliberation, they elected former Supreme Court Chief Justice Sushila Karki.

This wasn't government-sanctioned, and Karki's "election" had no legal force. But it demonstrated digital sortition's potential. As journalist Pranaya Rana observed, "It is much more egalitarian than a physical forum that many might not have access to. Since it is virtual and anonymous, people can also say what they want to without fear of retaliation."

The experiment also revealed risks. Participants feared infiltration—multiple accounts, coordinated manipulation. The fact-checking room mitigated misinformation, but as one observer noted, "anyone could easily manipulate users by infiltration." Digital platforms require robust security: identity verification, vote encryption, audit trails.

The necessity of pre-existing infrastructure also matters. Discord's ban had been lifted, enabling the debate. In countries with heavy internet censorship or poor connectivity, digital sortition faces technical barriers. Yet for youth-centric demographics disengaged from traditional politics, platforms like Discord offer accessible entry points.

Few advocates propose replacing elections entirely. Instead, hybrid models combine sortition's benefits with elections' familiarity.

Bicameral Sortition: Pair an elected chamber with a lottery-selected chamber. The elected house provides electoral legitimacy and specialized expertise. The sortition house offers descriptive representation and checks elite power. Bills must pass both chambers.

Sortition Oversight: Maintain elected executives and legislatures, but create randomly selected oversight boards with veto power over specific domains—budgets, ethics, constitutional amendments. This limits sortition to areas where elite capture is most problematic.

Phased Implementation: Start with municipal participatory budgeting, like Porto Alegre. Expand to local citizens' assemblies on specific issues. Build public trust through visible success before attempting national-level sortition.

Corporate Lottocracy: Apply sortition beyond government. Employee-owned firms could use dual boards: a professional board managing operations, and a randomly selected citizen board ensuring accountability. This addresses oligarchic tendencies within cooperatives.

Athens itself used a hybrid. Elections for generals and treasurers, lottery for the Council of 500 and juries. This balanced expertise with equality—a model with 2,500 years of proof of concept.

As faith in elections erodes—voter turnout declining, polarization rising, public trust cratering—sortition offers a path forward that's simultaneously ancient and cutting-edge.

The evidence is compelling. Ancient Athens governed successfully for two centuries. Porto Alegre transformed infrastructure. Ireland reformed its constitution. Belgium broke a political deadlock. Scotland, the UK, and dozens of other jurisdictions have produced policy recommendations that elected bodies couldn't.

The mechanisms are proven. Stratified random sampling ensures representation. Compensation enables participation. Expert briefing provides knowledge. Facilitated deliberation produces wisdom. Legal accountability requirements create pressure for adoption.

The obstacles are surmountable. Competence concerns are addressed through vetting, training, and collective deliberation. Legitimacy is built through transparency, publicity, and results. Participation barriers fall to outreach and resources. Implementation gaps close when assemblies have legal teeth.

What's needed now is will. Citizens must demand experiments. Governments must create space for them. Organizations like DemocracyNext, the Sortition Foundation, and People Powered are providing tools, training, and support. The MU Party advocates for full lottocracy with charter-based accountability.

The question isn't whether sortition can work—history and contemporary evidence say it can. The question is whether we're brave enough to let go of elections' comforting familiarity and embrace democracy's forgotten origins.

Because here's the thing: when Aristotle said elections are oligarchic and lotteries democratic, he wasn't making a philosophical point. He was describing observable reality. Elections systematically empower the few. Lotteries empower the many.

You don't need to be randomly selected to participate in this transformation. Advocate for participatory budgeting in your city. Support citizens' assemblies on contentious issues. Demand that your representatives respond when randomly selected citizens speak.

Democracy's future might not be found in better elections. It might be found in remembering that for most of human history, democracy meant something radically different—and radically more equal—than what we practice today.

The lottery for leadership isn't a gamble. It's a return to first principles.

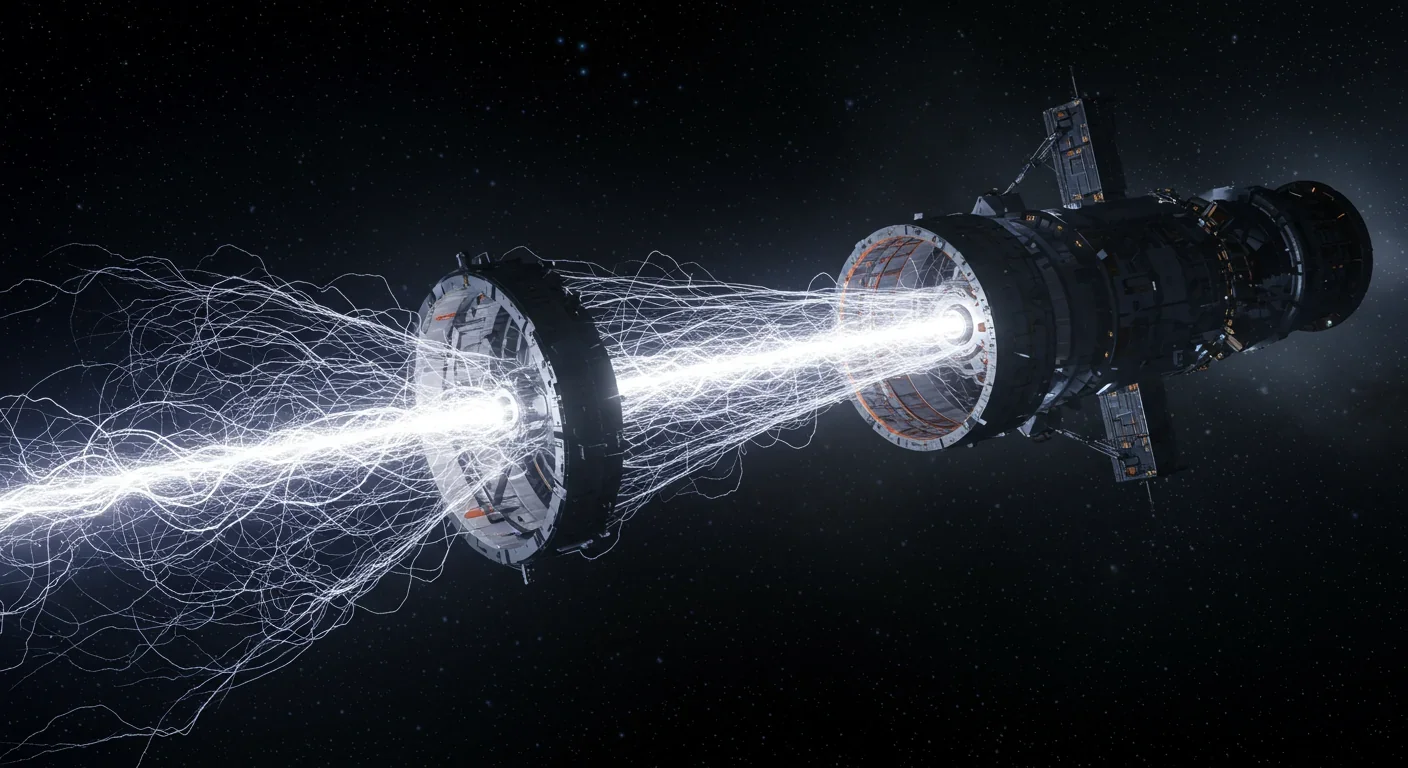

The Bussard Ramjet, proposed in 1960, would scoop interstellar hydrogen with a massive magnetic field to fuel fusion engines. Recent studies reveal fatal flaws: magnetic drag may exceed thrust, and proton fusion loses a billion times more energy than it generates.

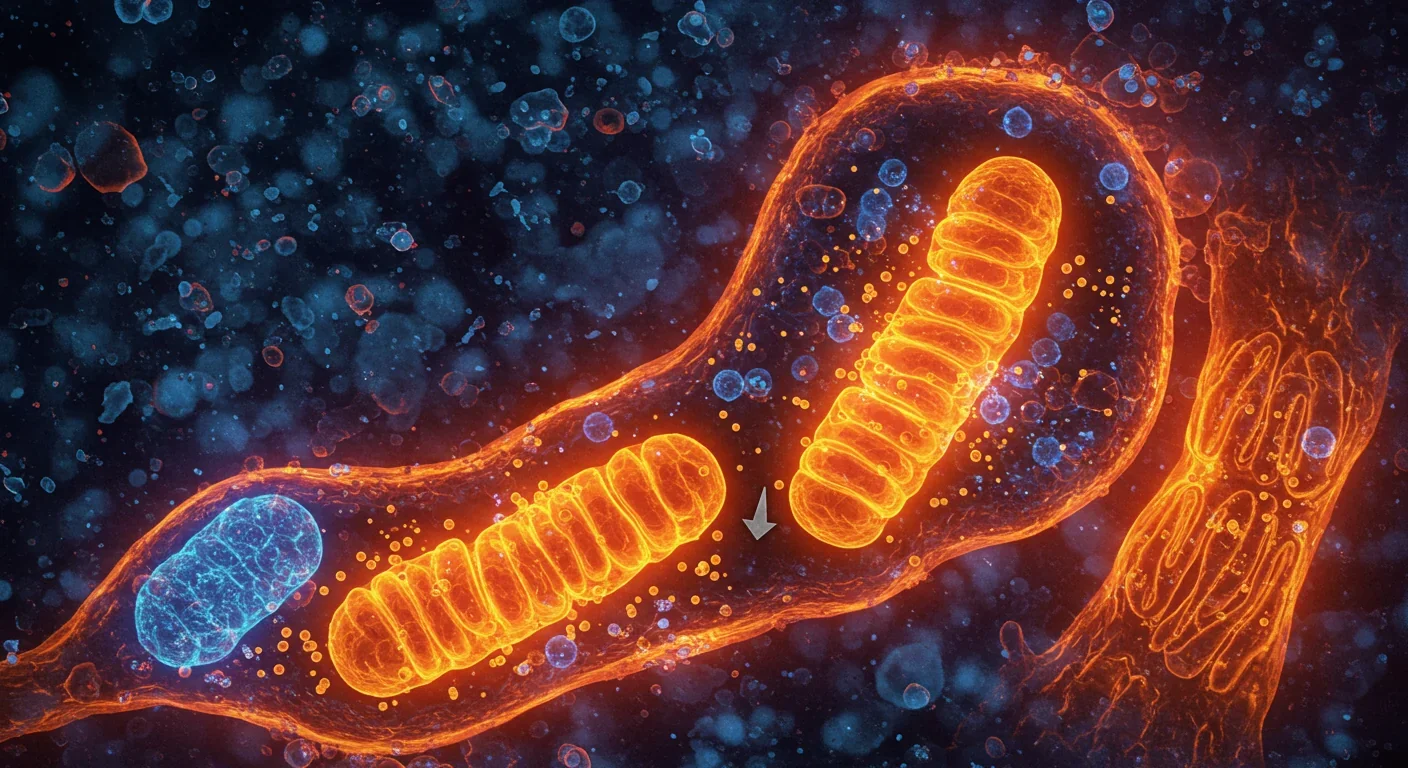

Mitophagy—your cells' cleanup mechanism for damaged mitochondria—holds the key to preventing Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, heart disease, and diabetes. Scientists have discovered you can boost this process through exercise, fasting, and specific compounds like spermidine and urolithin A.

Shifting baseline syndrome explains why each generation accepts environmental degradation as normal—what grandparents mourned, you take for granted. From Atlantic cod populations that crashed by 95% to Arctic ice shrinking by half since 1979, humans normalize loss because we anchor expectations to our childhood experiences. This amnesia weakens conservation policy and sets inadequate recovery targets. But tools exist to reset baselines: historical data, long-term monitoring, indigenous knowle...

Social media has created an 'authenticity paradox' where 5.07 billion users perform carefully curated spontaneity. Algorithms reward strategic vulnerability while psychological pressure to appear authentic causes creator burnout and mental health impacts across all users.

Scientists have decoded how geckos defy gravity using billions of nanoscale hairs that harness van der Waals forces—the same weak molecular attraction that now powers climbing robots on the ISS, medical adhesives for premature infants, and ice-gripping shoe soles. Twenty-five years after proving the mechanism, gecko-inspired technologies are quietly revolutionizing industries from space exploration to cancer therapy, though challenges in durability and scalability remain. The gecko's hierarch...

Cities worldwide are transforming governance through digital platforms, from Seoul's participatory budgeting to Barcelona's open-source legislation tools. While these innovations boost transparency and engagement, they also create new challenges around digital divides, misinformation, and privacy.

Every major AI model was trained on copyrighted text scraped without permission, triggering billion-dollar lawsuits and forcing a reckoning between innovation and creator rights. The future depends on finding balance between transformative AI development and fair compensation for the people whose work fuels it.