The Authenticity Paradox in Social Media Explained

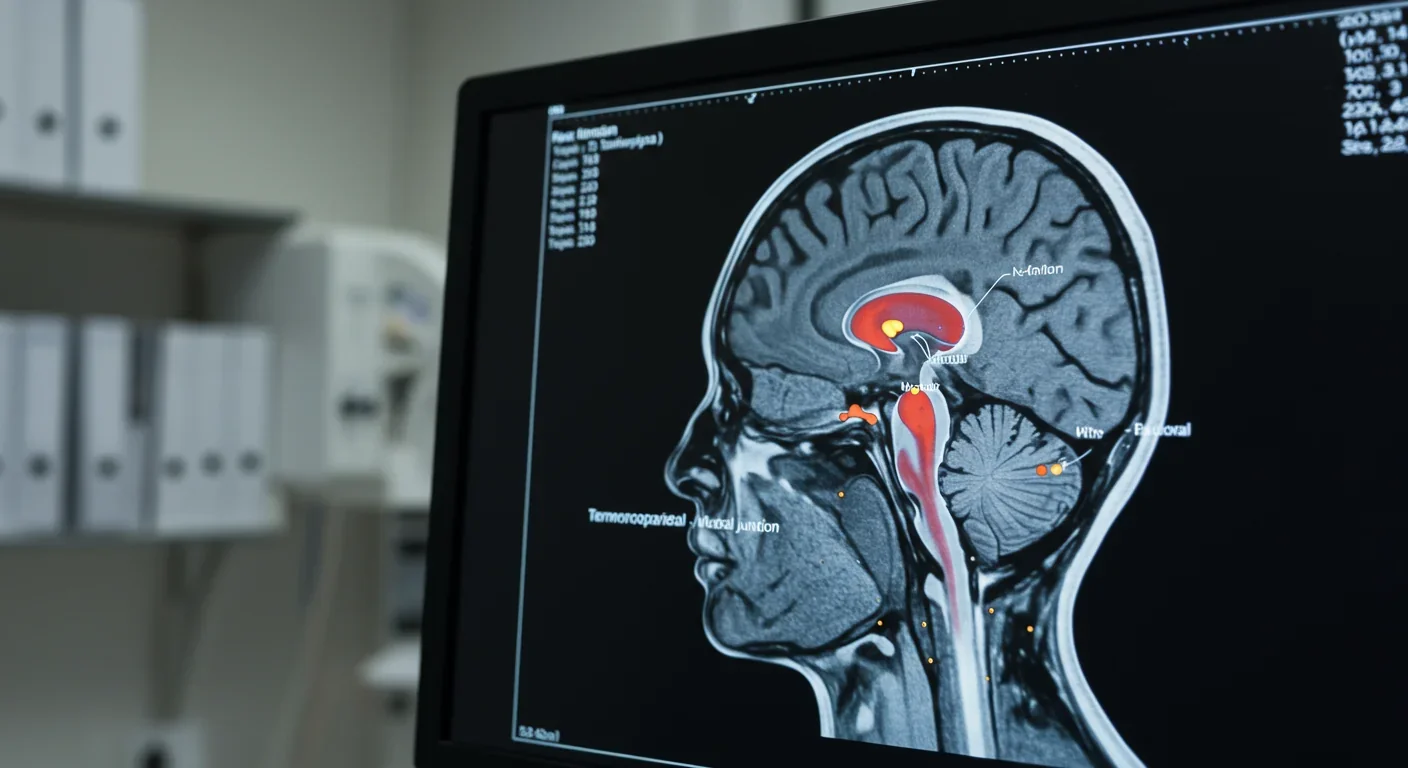

TL;DR: Humans are hardwired to see invisible agents—gods, ghosts, conspiracies—thanks to the Hyperactive Agency Detection Device (HADD), an evolutionary survival mechanism that favored false alarms over fatal misses. This cognitive bias, rooted in brain regions like the temporoparietal junction and medial prefrontal cortex, generates religious beliefs, animistic worldviews, and conspiracy theories across all cultures. Understanding HADD doesn't eliminate belief, but it helps us recognize when our pattern-seeking brains manufacture meaning from randomness.

In 1983, a Soviet lieutenant colonel named Stanislav Petrov sat in a bunker watching computer screens that suddenly screamed: INCOMING MISSILE ATTACK. Five American nuclear weapons were, according to his systems, streaking toward the Soviet Union. Protocol demanded he report it immediately, triggering a retaliatory strike that would kill hundreds of millions. But Petrov hesitated. Something felt wrong. He trusted his gut over the machines. It turned out to be sunlight reflecting off clouds—a false alarm that nearly ended civilization.

Petrov's brain, like yours, runs on a hair-trigger detection system designed to spot threats and agents—things with intentions. This system saved his life and ours. But it also fills our world with ghosts, gods, and conspiracies. Scientists call it the Hyperactive Agency Detection Device (HADD), and it's the reason humans across every culture and era have seen invisible hands behind the curtain of reality.

Your ancestor who heard a twig snap and assumed "tiger" instead of "wind" survived to pass on his genes. Your ancestor who paused to investigate became lunch. Natural selection didn't reward accuracy—it rewarded caution. Better a thousand false alarms than one fatal mistake. This evolutionary logic wired your brain to perceive agency everywhere, even when it's nowhere.

The hyperactive agency detection device emerged millions of years ago as a survival mechanism. Early humans faced constant threats from predators, rivals, and environmental hazards. Those who could quickly identify a threat—real or imagined—lived longer. Psychologists Kurt Gray and Daniel Wegner wrote: "The high cost of failing to detect agents and the low cost of wrongly detecting them has led researchers to suggest that people possess a Hyperactive Agent Detection Device, a cognitive module that readily ascribes events in the environment to the behavior of agents."

This "better safe than sorry" strategy becomes clear in a classic experiment with pigeons. B.F. Skinner placed hungry pigeons in boxes and dropped food pellets at random intervals. The birds quickly developed elaborate rituals—spinning, head-bobbing, wing-flapping—convinced their actions caused the food to appear. They detected agency in pure randomness. Humans do the same, but with higher stakes. When ancient peoples saw storms, disease, or drought, their hyperactive detectors inferred invisible agents: angry gods, vengeful spirits, malevolent forces.

Consider the statistics. Studies across 20 countries involving 57 researchers found that humans are naturally predisposed to believe in gods and an afterlife. Children below age five find it easier to believe in superhuman properties than to understand human limits. In one experiment, three-year-olds believed both their mother and God could see inside a closed box, but by age four they realized humans lack such powers—while still attributing omniscience to supernatural agents. The default setting isn't skepticism; it's belief in unseen minds.

The brain's neocortex, which averages only 2% of body weight, consumes approximately 20% of our caloric energy. This disproportionate investment powers sophisticated social cognition, including theory of mind—the ability to infer what others think and intend. But theory of mind creates a byproduct: when we can imagine hidden intentions in other people, we can imagine hidden intentions everywhere. A rustling bush becomes a stalking predator. A streak of bad luck becomes a curse. A pattern of coincidences becomes a conspiracy.

The neural architecture of agency detection spans multiple brain regions working in concert. The temporoparietal junction (TPJ), located where the temporal and parietal lobes meet, integrates information from the thalamus, limbic system, and visual, auditory, and somatosensory systems. The TPJ plays a crucial role in distinguishing self from other and in theory of mind. When the right TPJ is damaged, people struggle to attribute beliefs and intentions to others—and their moral judgments shift from considering intentions to focusing solely on outcomes.

In a landmark study, researchers used transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to temporarily disrupt the right TPJ while participants made moral judgments about attempted harms. With the TPJ offline, people judged accidental harms more harshly and intentional attempts more leniently. They lost the ability to weight mental states appropriately. The experiment revealed that the TPJ acts as a neural switchboard for inferring agency, and when it malfunctions, our perception of intentional action warps.

But agency detection doesn't wait for conscious deliberation. It happens fast—within 165 milliseconds. Magnetoencephalography studies show that when people see faces in random patterns (a phenomenon called pareidolia), the fusiform face area activates at the same time and location as when seeing actual faces. A 2022 EEG study went further, showing that the frontal and occipitotemporal cortexes activate before people consciously recognize a face. Kang Lee, a professor of applied psychology, explains: "The inferior frontal gyrus is a very interesting area; it tells the visual cortex to see a face, even when there is none." Your brain literally calls the shots, priming your visual system to detect agency before your eyes send clear input.

This top-down processing means your expectations shape perception. In one fMRI experiment, participants were told that half of a series of images contained faces. When shown pure visual noise, they reported seeing faces 34% of the time—and their inferior frontal gyrus and visual cortex lit up as if faces were actually present. The brain, anticipating agents, manufactured them from randomness.

The salience network, composed of the anterior insula and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, acts as a neural alarm system. It detects emotionally or contextually significant stimuli and signals other brain networks to pay attention. When combined with the default mode network—active during self-reflection, theory of mind, and mind-wandering—the salience network creates a cognitive environment ripe for perceiving hidden agents. The default mode network engages the medial prefrontal cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, and precuneus, regions associated with imagining the mental states of others. When these networks interact, ambiguous stimuli get interpreted through the lens of agency.

Animism—the belief that objects, places, and natural phenomena possess spiritual essence and intentionality—appears in virtually every hunter-gatherer society studied by anthropologists. The Mbuti of the Ituri Forest, the San of the Kalahari Desert, and the Copper Inuit of the Arctic all attribute agency to animals, plants, rocks, rivers, and weather systems. The ǃKung people of Southern Africa recognize a Supreme Being, ǃXu, the Creator and Upholder of life, alongside spirits of the dead (llgauwasi) who live in the sky, interact with humans, and must be feared, prayed to, and appeased.

In Siberia, Eveny hunters describe animals, trees, and rivers as "people like us" because they move, grow, and breathe. Before a hunt, the hunter must "close" his body to avoid being detected by animal spirits, then "re-open" it afterward, often tasking a child with carrying the prey home to fool the spirits. Among the Yup'ik of Alaska, the ocean "has eyes, sees everything, and does not like it when persons fail to follow traditional abstinence practices." These beliefs aren't cultural quirks—they're expressions of a universal cognitive tendency to detect intentionality in ambiguous phenomena.

Even in industrialized societies, agency detection persists. Technology itself becomes animate. In Japan, Shinto practitioners have held funerals for robot dogs. Some animistic cultures incorporate cars and robots into their cosmologies, attributing sentience when the objects move autonomously or when spirits are invoked during rituals. The cognitive mechanism remains constant; only the targets change.

The persistence of animism across geography and time suggests the hyperactive agency detector emerged early in human evolutionary history and was maintained through cultural transmission. Cross-cultural studies show people do not hold natural and supernatural explanations in mutually exclusive ways. Instead, they layer supernatural agency atop natural causation. Illness has both a biological cause (germs) and a moral cause (a violated taboo). Death results from injury and from the anger of ancestors. This dual-process reasoning reflects the brain's parallel systems: one for mechanical causation, another for intentional agency.

Archaeological evidence supports this timeline. Around 100,000 years ago, early humans began wearing necklaces and other body ornaments, suggesting self-awareness and concern for others' perceptions—key components of theory of mind. By 35,000 years ago, the development of autobiographical memory enabled humans to fully grasp their own mortality. Faced with the certainty of death, they created afterlives. The first unequivocal burials with grave goods appear in this period, indicating belief in a continued existence requiring provisions. Before gods emerged, there were ancestors—revered dead whose agency persisted beyond the grave.

As societies grew larger and more complex, supernatural agents evolved. Small foraging bands required only ancestor spirits and nature deities. Agricultural civilizations needed gods who monitored moral behavior, punished transgressions, and enforced cooperation among strangers. Studies of 200 utopian communes in the 19th century found that religious communes, which imposed costly rituals and demanded sacrifice, outlasted secular ones by dramatic margins: 39% of religious communes survived 20 years, compared to only 6% of secular communes. Shared belief in supernatural agents who watch and judge creates powerful social cohesion.

Religious experiences activate specific brain networks. Functional MRI studies of Carmelite nuns asked to recall their most intense mystical experiences showed widespread activation—no single "God spot," but coordinated activity across the temporal lobes, medial prefrontal cortex, posterior cingulate, and reward circuits. Patients with temporal lobe epilepsy frequently report hyperreligiosity, a sense of divine presence, and compulsive religious writing (hypergraphia). Neurologist Norman Geschwind first cataloged these traits, now known as Geschwind syndrome.

In the 1980s, neuroscientist Michael Persinger developed the "God Helmet," a device that stimulated the temporal lobes with weak magnetic fields. Many participants reported sensing an invisible presence. However, a 2005 replication study by Pehr Granqvist found that suggestibility, not magnetic fields, predicted the experiences. Participants primed to expect paranormal phenomena reported them regardless of whether the helmet was active. This finding underscores a critical point: agency detection is so sensitive that expectation alone can trigger it.

The dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC), a key node in the default mode network, integrates emotion, self-reference, and social cognition. It connects to the amygdala (emotion processing) and hippocampus (memory), enabling it to color perceptions of agency with fear, awe, or longing. When actors perform a character, fMRI scans show suppressed dmPFC activity, suggesting the region mediates self-referential processing that competes with inferring external agency. Transcranial magnetic stimulation to the dmPFC disrupts social judgments, confirming its causal role in attributing intentions.

The robustness of this system becomes apparent in experiments inducing "presence hallucinations"—the vivid sensation of an invisible being nearby. Researchers at the Brain Mind Institute used a robot to delay and distort participants' somatosensory-motor feedback. When the robot touched participants' backs with a 500-millisecond delay mirroring their own hand movements, healthy volunteers reported feeling an invisible presence, often turning around to search for it or even offering it a chair. The brain network activated—ventral premotor cortex, inferior frontal gyrus, posterior superior temporal sulcus—matched the lesion network seen in neurological patients who spontaneously experience presence hallucinations.

These findings bridge anthropology and neuroscience. Guthrie's 1980s anthropomorphism account argued humans have a low-level perceptual tendency to detect agency in ambiguous environments. Barrett's 2000 formalization introduced the HADD concept, framing it as a mental module producing high false-positive rates. The robot-induced presence experiments demonstrate that agency detection arises from self-monitoring: when the brain's model of self becomes desynchronized from sensory input, it infers an external agent to explain the discrepancy.

The same cognitive bias that generates gods and ghosts also fuels conspiracy theories. Apophenia—the tendency to perceive meaningful connections in unrelated events—stems from the same neural circuitry as agency detection, particularly the temporoparietal junction and medial prefrontal cortex. A 2017 study found that people who detected patterns in random noise were significantly more likely to endorse conspiracy theories like 9/11 being an inside job or the CIA conducting mind-control experiments.

Conspiracy beliefs don't indicate psychopathology in most cases. Psychologists once attributed conspiratorial thinking to paranoia, schizotypy, or narcissism, but the current scientific consensus holds that most conspiracy theorists simply exaggerate cognitive tendencies universal to the human brain. Agent detection, pattern recognition, and causal reasoning—adaptive in ancestral environments—misfire in the information-saturated modern world.

However, research reveals a crucial nuance. Studies conflating implausible conspiracy theories (shape-shifting reptilians, flat Earth) with plausible ones (government surveillance, corporate malfeasance) find that only belief in implausible theories correlates negatively with cognitive reflection and analytical thinking. Belief in plausible conspiracies shows no such correlation. The NSA PRISM program and FBI COINTELPRO were real conspiracies later proven true. Dismissing all conspiracy thinking as flawed cognition ignores this distinction.

The hyperactive agency detector thrives in uncertainty. When events lack clear causes—economic crashes, pandemics, political upheavals—people infer hidden agents orchestrating outcomes. Studies show that belief in conspiracy theories spikes during periods of social instability and perceived powerlessness. Evolutionary psychologists suggest suspecting conspiracies may itself be an adaptive mechanism that helped humans survive dangerous outgroup coalitions. In tribal environments, rival groups did conspire to raid, steal, and kill. Vigilance against coordinated threats made sense.

But modernity inverts the cost-benefit ratio. False positives no longer carry trivial costs. Vaccine hesitancy driven by conspiracy beliefs kills. Election denialism undermines democracy. Climate change denial delays action. The brain's Paleolithic wiring, optimized for small-scale social threats, struggles with abstract, systemic risks and statistical reasoning.

Justin L. Barrett, a prominent cognitive scientist of religion, describes belief in God as "an almost inevitable consequence of the kind of minds we have." He notes: "Most of what we believe comes from mental tools working below our conscious awareness." The hyperactive agency detector operates automatically, pre-consciously, and cross-culturally. Skepticism, by contrast, requires deliberate effort to override default intuitions.

Consider confirmation bias—the tendency to seek, interpret, and remember information supporting prior beliefs while ignoring contradictory evidence. Confirmation bias reinforces agency detection. Once someone perceives a pattern or agent, they selectively gather evidence confirming it. A believer in ghosts interprets creaking floorboards, cold drafts, and electronic glitches as manifestations. A skeptic attributes them to settling houses, thermodynamics, and hardware failures. Both process the same data through different filters, but the believer's interpretation aligns with the brain's default setting.

Error management theory explains why biases toward false positives persist. Evolutionary pressures favor minimizing the costlier error. For mate selection, men historically overperceived women's sexual interest—a false positive cost embarrassment, while a false negative (missing a mating opportunity) cost reproductive success. Women underperceived men's commitment intent—a false positive (trusting an uncommitted partner) cost survival resources for offspring, while a false negative (rejecting a committed partner) carried lower costs. These asymmetries shaped systematic biases.

Applied to agency detection, the logic is stark: mistaking wind for a predator costs a moment of fear; mistaking a predator for wind costs your life. Natural selection ruthlessly favored the paranoid.

Understanding HADD offers practical benefits. Recognizing the bias doesn't eliminate it—that's neurologically impossible—but metacognition, thinking about thinking, enables better calibration. When you feel certain someone is watching you, remember your TPJ might be generating that feeling from ambiguous sensory input. When coincidences seem impossibly meaningful, recall that humans reliably overestimate the improbability of random clustering.

Pareidolia, seeing faces in clouds, tree bark, or electrical outlets, demonstrates HADD in a harmless form. Researchers at Johns Hopkins developed a "signal detection pareidolia test" to measure hallucination proneness. High scorers perceive faces in noise more often and show earlier frontal cortex activation. Interestingly, pareidolia has therapeutic potential: encouraging people to look for patterns in their environment can enhance focus, creativity, and mood. The bias isn't inherently bad—it's a powerful tool when understood and directed.

In clinical contexts, understanding agency detection helps explain conditions like Parkinson's disease, where patients frequently experience presence hallucinations. The sensorimotor self-monitoring account suggests bodily posture and movement therapies could modulate HADD activation, offering new treatment strategies.

For the general population, critical thinking education should emphasize cognitive biases. Teaching children about HADD, confirmation bias, and apophenia equips them to navigate a world saturated with misinformation. But lessons must avoid condescension. Belief in supernatural agents isn't irrational—it's a rational response to brain architecture shaped by evolutionary pressures. Vitalistic causal reasoning, attributing life force to natural phenomena, represents a category error not widely taught in mainstream psychology. Explaining why minds generate these beliefs fosters self-awareness without disparaging deeply held convictions.

Religion may be less likely to thrive in urban populations with strong social support networks, as research suggests. When secular institutions provide community, healthcare, education, and security, the adaptive advantages of religious affiliation diminish. Yet even in highly secular societies like Scandinavia, supernatural beliefs persist in subtler forms—astrology, crystal healing, manifestation culture. The underlying cognitive mechanisms remain active, finding new outlets.

Some researchers have explored genetic influences. The "God gene" hypothesis proposed that the VMAT2 gene, which encodes a vesicular monoamine transporter regulating serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine, predisposes individuals toward spiritual experiences. Twin studies show approximately 40% of variance in self-transcendence scores is heritable. However, critics note that VMAT2 accounts for less than 1% of that variance—it's a neurotransmitter pump, not a divine hotline. Specific religious beliefs have no genetic basis; they're cultural units, memes transmitted through learning.

The hyperactive agency detector, as an exaptation of broader predictive brain mechanisms, will not disappear. It's too deeply embedded in perception, emotion, and social cognition. But cultural evolution can shape its expression. Societies that value empirical evidence, statistical literacy, and scientific reasoning create environments where critical thinking competes with intuitive biases. The tension between System 1 (fast, automatic, intuitive) and System 2 (slow, deliberate, analytical) thinking defines the modern struggle for truth.

Navigating this tension requires humility. The brain that sees faces in clouds also recognizes genuine faces in crowds. The pattern detector that generates conspiracy theories also uncovers real corruption. The hyperactive agency detector that populated history with gods and ghosts also enabled social cooperation, moral reasoning, and the profound human capacity for empathy.

Stewart Guthrie, whose 1980 essay pioneered cognitive theories of religion, wrote: "Religion is difficult to define because definitions imply theories." Any account of why humans believe in gods must also explain what all religions share. The answer appears to be agency—intentional minds behind events. From ancestor worship in the Paleolithic to algorithmic deities in science fiction, humans project mind into matter. We cannot help it. We are, by design, meaning-making machines in a universe that offers endless ambiguity.

Psychologists are a skeptical bunch, yet as Barrett observes, having a scientific explanation for belief doesn't invalidate the belief itself. Suppose science convincingly explains why you think your spouse loves you—evolutionary advantages of pair bonding, oxytocin release, neural reward activation. Should you stop believing they love you? The explanation and the experience occupy different domains. Understanding HADD doesn't banish gods any more than understanding vision banishes color.

The evolutionary perspective offers a surprising consolation: if natural selection wired us to detect agency, perhaps agency is a fundamental feature of reality, not an illusion. Perhaps minds are more prevalent than materialism assumes. Or perhaps the hyperactive detector, for all its false positives, captures something true—that in a universe capable of producing conscious observers, agency isn't rare but ubiquitous, woven into the fabric of emergence itself.

Whether you interpret the hyperactive agency detection device as a glitch or a glimpse, it remains a defining feature of human consciousness. The next time you feel watched in an empty room, hear whispers in white noise, or sense a presence just beyond perception, remember: your brain is doing exactly what evolution designed it to do. The question isn't whether you'll detect agents in randomness—you will. The question is what you'll do with that knowledge.

Recent breakthroughs in fusion technology—including 351,000-gauss magnetic fields, AI-driven plasma diagnostics, and net energy gain at the National Ignition Facility—are transforming fusion propulsion from science fiction to engineering frontier. Scientists now have a realistic pathway to accelerate spacecraft to 10% of light speed, enabling a 43-year journey to Alpha Centauri. While challenges remain in miniaturization, neutron management, and sustained operation, the physics barriers have ...

Epigenetic clocks measure DNA methylation patterns to calculate biological age, which predicts disease risk up to 30 years before symptoms appear. Landmark studies show that accelerated epigenetic aging forecasts cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and neurodegeneration with remarkable accuracy. Lifestyle interventions—Mediterranean diet, structured exercise, quality sleep, stress management—can measurably reverse biological aging, reducing epigenetic age by 1-2 years within months. Commercial ...

Data centers consumed 415 terawatt-hours of electricity in 2024 and will nearly double that by 2030, driven by AI's insatiable energy appetite. Despite tech giants' renewable pledges, actual emissions are up to 662% higher than reported due to accounting loopholes. A digital pollution tax—similar to Europe's carbon border tariff—could finally force the industry to invest in efficiency technologies like liquid cooling, waste heat recovery, and time-matched renewable power, transforming volunta...

Humans are hardwired to see invisible agents—gods, ghosts, conspiracies—thanks to the Hyperactive Agency Detection Device (HADD), an evolutionary survival mechanism that favored false alarms over fatal misses. This cognitive bias, rooted in brain regions like the temporoparietal junction and medial prefrontal cortex, generates religious beliefs, animistic worldviews, and conspiracy theories across all cultures. Understanding HADD doesn't eliminate belief, but it helps us recognize when our pa...

The bombardier beetle has perfected a chemical defense system that human engineers are still trying to replicate: a two-chamber micro-combustion engine that mixes hydroquinone and hydrogen peroxide to create explosive 100°C sprays at up to 500 pulses per second, aimed with 270-degree precision. This tiny insect's biochemical marvel is inspiring revolutionary technologies in aerospace propulsion, pharmaceutical delivery, and fire suppression. By 2030, beetle-inspired systems could position sat...

The U.S. faces a catastrophic care worker shortage driven by poverty-level wages, overwhelming burnout, and systemic undervaluation. With 99% of nursing homes hiring and 9.7 million openings projected by 2034, the crisis threatens patient safety, family stability, and economic productivity. Evidence-based solutions—wage reforms, streamlined training, technology integration, and policy enforcement—exist and work, but require sustained political will and cultural recognition that caregiving is ...

Every major AI model was trained on copyrighted text scraped without permission, triggering billion-dollar lawsuits and forcing a reckoning between innovation and creator rights. The future depends on finding balance between transformative AI development and fair compensation for the people whose work fuels it.