Care Worker Crisis: Low Pay & Burnout Threaten Healthcare

TL;DR: The global internet is fracturing into national territories as governments assert digital sovereignty through censorship exports (China's Great Firewall sold to Myanmar, Pakistan, Ethiopia), regulatory enforcement (EU's Digital Services Act fining Google €2.95B), and data localization (India's sector-specific rules). With over 600GB of Great Firewall code leaked in September 2025, we now have proof that authoritarianism is being commodified and sold globally. The result: tech companies face impossible compliance costs across conflicting jurisdictions, while citizens experience radically different internets depending on location. The question isn't whether fragmentation continues—it will—but whether humanity can build frameworks that respect sovereignty without sacrificing the innovation and collaboration that made the internet revolutionary.

On September 11, 2025, over 600 gigabytes of China's most guarded secret spilled across the internet. The Great Firewall—the world's most sophisticated censorship machine—had been cracked open. Inside weren't just technical blueprints, but something far more alarming: receipts for a global business model. China wasn't just censoring its own citizens anymore. It was selling censorship as a service.

This leak revealed what tech analysts had suspected but couldn't prove: digital authoritarianism has gone commercial. The same deep packet inspection systems that block Facebook in Beijing now monitor 81 million connections simultaneously in Myanmar. The same SSL fingerprinting that identifies VPN users in Shanghai is being deployed in Pakistan, Ethiopia, and Kazakhstan. Censorship isn't a domestic policy anymore—it's an export industry.

Welcome to the new internet: fragmented, surveilled, and carved into national territories as fiercely contested as any physical border.

For two decades, China's Great Firewall stood as a monument to national digital control. It blocks approximately 311,000 domains, throttles cross-border traffic, and uses sophisticated deep packet inspection to identify and eliminate unauthorized content. Wikipedia, Google, Facebook, Twitter—all blocked. Chinese citizens live in a digital walled garden where Baidu replaces Google, WeChat substitutes for WhatsApp, and Weibo fills the Twitter void.

But the September leak exposed a transformation. The Great Firewall isn't just infrastructure—it's intellectual property. A commercial platform called "Tiangou" (天狗) packages the entire censorship stack into a turnkey solution: "Great Firewall in a box."

The leaked files contain full build systems for deep packet inspection platforms, including modules for VPN detection, SSL fingerprinting, and comprehensive session logging. Technical documentation shows how Tiangou transitioned from HP and Dell servers to domestic Chinese hardware following US sanctions—a revealing detail about how geopolitical tensions drive technical infrastructure decisions.

Most disturbing: deployment logs. Myanmar's state-run telecoms installed Tiangou across 26 data centers, integrating it directly into core internet exchange points. Pakistan incorporated Geedge's DPI infrastructure into its WMS 2.0 surveillance system for blanket mobile monitoring. Ethiopia and Kazakhstan followed suit. These aren't isolated deployments—they represent a systematic export of state-grade digital control infrastructure to allied regimes.

The business model is clear: authoritarian governments no longer need to develop surveillance technology domestically. They can buy it off the shelf, complete with training and support. Digital sovereignty has been commodified.

While China exports censorship, Europe is building regulatory walls. The European Union's Digital Services Act (DSA), fully applicable since early 2024, represents the most comprehensive attempt to assert digital sovereignty through law rather than infrastructure.

The DSA targets Very Large Online Platforms (VLOPs) and Very Large Online Search Engines (VLOSEs)—any service with more than 45 million EU users. These platforms face stringent requirements: algorithmic transparency, content moderation obligations, mandatory risk assessments for systemic threats, and severe penalties for non-compliance.

The regulation explicitly addresses concerns about algorithmic manipulation. Article 25 requires platforms to design interfaces that don't impair users' autonomous decisions—banning infinite scrolling, autoplay, and gamification tactics that exploit human psychology. Article 26 demands real-time transparency about advertising parameters, going beyond GDPR's pre-processing disclosure requirements.

For VLOPs, the regulatory burden is even heavier. They must conduct Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs) when processing personal data for content moderation or targeted advertising. The European Data Protection Board's September 2025 guidelines clarify that DSA compliance cannot exist separately from GDPR adherence—platforms must satisfy both simultaneously or face dual penalties.

The enforcement mechanism reveals Europe's strategic intent. The DSA grants the European Commission unprecedented digital enforcement powers, with fines reaching up to 6% of global annual turnover. In September 2025, the Commission fined Google €2.95 billion for distorting advertising technology markets—a signal that European digital sovereignty will be defended through aggressive antitrust action.

But regulatory power creates political vulnerability. Bruegel, Europe's influential think tank, argues that the Commission's expanded enforcement role makes it susceptible to external pressure and internal capture. They propose an independent European Digital Authority—a body insulated from political interference that could enforce rules impartially while strengthening Europe's bargaining position against US trade threats.

The logic: delegation as credible commitment. By transferring enforcement to an independent authority, the Commission "burns the bridge"—it can't promise to ease enforcement in exchange for trade concessions because it no longer controls the lever. In game theory terms, this makes Europe's regulatory stance more credible and harder to undermine.

India has chosen a third path: sector-specific data localization combined with incentives for domestic infrastructure. Unlike China's comprehensive blocking or Europe's regulatory approach, India tailors requirements to strategic sectors while leaving most data flows open.

The Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDPA) 2023 establishes India's framework. It requires explicit consent for data collection, grants deletion rights, mandates 72-hour breach notification, and creates a Data Protection Board with authority to levy fines up to ₹250 crore (approximately $30 million). Significantly, the Act permits cross-border data transfers unless the destination country appears on a government-issued "negative list" published in the official Gazette.

But sectoral rules layer additional requirements. The Reserve Bank of India requires payment systems and customer financial data to be stored locally. Healthcare data faces similar restrictions under sector-specific regulations. Telecommunications operators must maintain data within Indian borders. E-commerce platforms navigate complex compliance requirements that vary by the nature of data processed.

India's strategy reveals sophisticated economic thinking. Rather than simply mandating localization, the government offers incentives: tax rebates, land grants, and streamlined licensing for green, AI-enabled data centers that meet domestic residency requirements. This transforms compliance from pure cost to competitive differentiator. Companies that invest in Indian infrastructure gain preferential treatment—turning data sovereignty into an industrial policy tool.

The approach may serve as a template for other emerging economies balancing openness with protection. By combining broad legal frameworks with sector-specific rules and a negative-list approach to cross-border transfers, India maintains flexibility while asserting sovereign control over strategic data.

Digital sovereignty isn't just about security or privacy—it's reshaping global commerce. Multinational tech companies face a choice: build region-specific infrastructure or abandon markets. Increasingly, they're choosing the former, and the results are profound.

Consider the cloud computing industry. Three US companies—Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud Platform—control 70% of Europe's cloud market. European governments, recognizing this dependency as a strategic vulnerability, are pushing for "cloud sovereignty." The EU plans to triple data center capacity over seven years, develop EU-sourced strategic enablers, and update its Cybersecurity Act to include mandatory certification for cloud providers.

The Franco-German Economic Agenda, adopted at an August 2025 summit, explicitly calls for strengthening digital sovereignty through cloud infrastructure, digital public infrastructure, and joint positions to enhance European competitiveness. This isn't reactive regulation—it's proactive industrial policy designed into economic strategy.

The compliance costs are staggering. ECIPE economic modeling estimates that forced data localization in China could depress GDP by approximately 1.1%. When localization rules become sector-specific—as in India—the compliance burden multiplies. Multinational corporations must deploy customized technology solutions, relocate data centers, adjust contracts to meet local regulations, and maintain legal expertise across jurisdictions.

Africa illustrates the challenge for global providers. Thirty-nine African countries have enacted data protection laws, and 36 African Union members maintain some form of regulation—yet Africa accounts for less than 1% of colocation data center capacity and averages only 0.1 data centers per 1 million internet users, compared to a global benchmark of 0.9. The regulatory imperative exists, but infrastructure lags dramatically.

This creates opportunities for regional players. Angola Cables manages an extensive subsea cable and international backbone network accessing over 900 data centers and 300 cloud on-ramps across Europe, Africa, Brazil, and the US—a hybrid model that maintains data sovereignty without hard silos. Companies like Wire, the European secure communications platform used by over 1,800 organizations including BMW and the German government, emphasize sovereignty-by-design: servers in Germany, backups in Ireland, end-to-end encryption, and explicit protection from extraterritorial access.

The economic logic is clear: digital sovereignty creates regulatory fragmentation, which increases compliance costs, which advantages local players who only need to satisfy one jurisdiction. The "Brussels Effect"—where EU regulations become de facto global standards—now competes with the "Beijing Model" and the "Mumbai Framework." Instead of one internet, we're building many.

Proponents of digital sovereignty cite legitimate security concerns. The CrowdStrike incident—when a faulty software update crashed millions of Windows systems globally—demonstrated how concentrated digital infrastructure creates catastrophic single points of failure. The US CLOUD Act, which authorizes American officials to seize data stored abroad by US companies, shows how legal jurisdiction can override physical location.

For military and defense applications, sovereignty isn't optional—it's mandatory. A 2025 paper on military AI-based cyber security argues that digital sovereignty control requires a multi-layered framework combining legal jurisdiction, technical architecture, stakeholder governance, and risk mitigation. The UK's Data Strategy for Defence aims to treat data as a strategic asset by 2025, prioritizing sovereignty explicitly.

But critics see protectionism dressed as security. Storing data locally doesn't inherently improve security—encryption, access controls, and segmentation matter more than geography. The Great Firewall simultaneously enforces state censorship and protects domestic tech companies from foreign competition, allowing Baidu, Tencent, and Alibaba to thrive in a market closed to Google, Facebook, and Amazon.

Data localization can hamper innovation by restricting access to cross-border datasets critical for AI, blockchain, and cloud services. China's AI companies are forced to build separate data environments for domestic and international operations, fragmenting development and slowing progress. European companies complain that GDPR compliance costs divert resources from innovation to legal departments.

The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP)—the world's largest free trade agreement—permits broad data localization exceptions, including for "financial" data. This flexibility undermines the agreement's data flow provisions, creating loopholes that countries exploit for economic rather than security reasons. The result: digital trade agreements that entrench fragmentation rather than reduce it.

Digital services taxes illustrate the geopolitical dimension. More than a dozen nations have introduced taxes ranging from 1.5% to 12% on digital services revenue—ostensibly to ensure tech giants pay fair shares, but also serving as leverage in trade negotiations. These taxes target primarily US companies and have become bargaining chips in broader economic disputes.

The tension is real: legitimate security needs compete with economic protectionism, and it's often impossible to disentangle the two.

Russia demonstrates what digital sovereignty looks like when pursued without compromise. The country operates a semi-isolated internet built on state-controlled infrastructure, domestic software platforms, and aggressive content restrictions.

As of 2020, 122 million Russians (85% of the population) use the internet, but their experience differs fundamentally from users elsewhere. The government maintains access to every citizen's internet search history. Major fiber optic lines are held by state-controlled Rostelecom and railways-affiliated Transtelecom, limiting foreign network participation. The government-managed Gosuslugi portal centralizes public services, while Astra Linux—a domestic operating system—reduces dependence on foreign software.

Content restrictions have intensified. In 2025, Russia banned audio and video calls on WhatsApp and Telegram. On September 1, 2025, accessing "manifestly extremist material" became a felony—a category that includes LGBTQ content, Greenpeace materials, satanism, and political movements like Alexei Navalny's opposition. Freedom House rates Russia's internet "Not Free."

The architecture reveals deliberate design. Russia doesn't just filter content—it builds domestic alternatives. Where China blocks Google but offers Baidu, Russia restricts WhatsApp but preserves state-monitored alternatives. The strategy combines infrastructure sovereignty (state ownership of networks), software sovereignty (domestic operating systems), and content sovereignty (legal prohibitions on foreign platforms).

This creates a digital ecosystem insulated from external influence but also isolated from global innovation. Russian internet speeds (75.91 Mbps average download in 2020) lag global leaders, and domestic platforms lack the scale and features of international competitors. The trade-off is explicit: control over connectivity.

Digital sovereignty increasingly means controlling what content citizens see—even on foreign platforms. The UK's September 2025 proposal to mandate YouTube promotion of BBC and ITV content illustrates how governments seek to reassert authority over digital spaces.

Lisa Nandy, UK Minister for Culture and Media, warned: "If we need to regulate, we will." The government already requires smart TVs to give prominence to BBC content; extending this to YouTube and TikTok would force algorithmic changes benefiting public service media. Kevin Mayer, co-founder of Candle Media, explained the stakes: "Social media have the central ability to control the media experience of the audience... Sometimes, YouTube decides to take their programmatic ad interface and favor our content. Other times, it favors competitive content."

This is sovereignty over attention—not just data. Governments recognize that platform algorithms shape public discourse more powerfully than traditional media regulation ever could. If YouTube's recommendation engine determines what citizens watch, then YouTube, not elected officials, controls the information environment.

Nick Clegg, Meta's policy chief, warned of "balkanization": "We have a Chinese internet, a Russian internet and a western internet which is itself fragmenting." The metaphor is apt. Just as the Balkans fractured into competing nation-states, the internet is splintering into digital territories with hardening borders.

The EU's antitrust enforcement against Google—€2.95 billion for distorting advertising markets—serves dual purposes: punishing anticompetitive behavior and demonstrating that American tech giants don't operate above European law. Google dismissed the penalty as "unjustified," but its appeal will likely extend through EU courts for years, creating ongoing uncertainty about market access.

The threat of forced divestitures looms. If European regulators conclude that behavioral remedies (rules about conduct) can't prevent market distortion, they may mandate structural remedies (breaking up companies). This would set a global precedent, emboldening regulators in India, Brazil, and Japan to pursue similar actions.

Tech companies face a dilemma: accept national content requirements and become instruments of state policy, or resist and risk losing market access. Either way, the internet as a unified global space erodes.

Digital sovereignty debates often focus on data and platforms, but physical infrastructure determines what's possible. Submarine cables carry over 95% of global internet traffic—and control over those cables increasingly defines geopolitical power.

The recently formed International Advisory Body for Submarine Cable Resilience reflects growing recognition that cables represent strategic vulnerability. Accidental damage disrupts economies; deliberate sabotage could cripple nations. The International Telecommunication Union now emphasizes standards for cable landing protection and sovereign traffic routing.

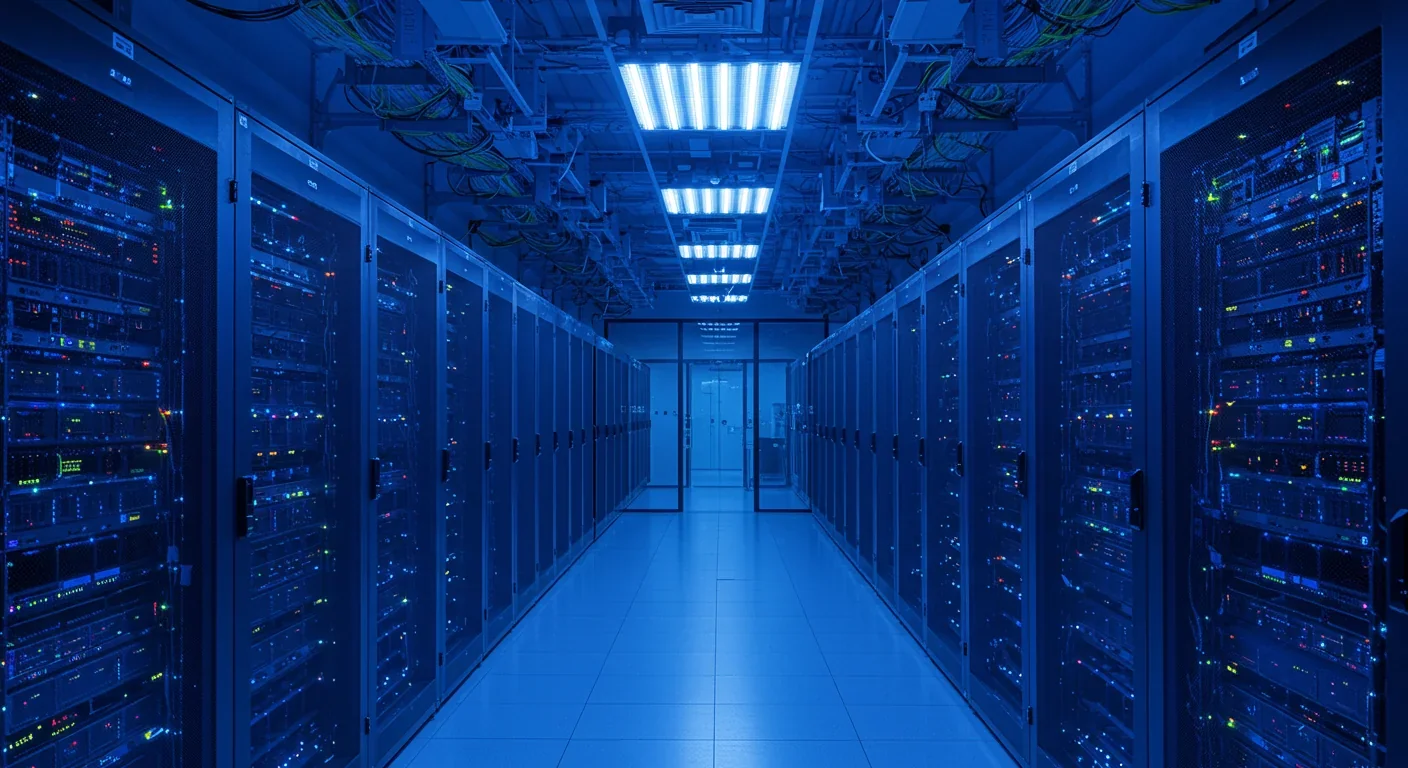

Cloud computing compounds the challenge. Data centers are evolving into "AI factories"—facilities that don't just store data but process it for machine learning, autonomous systems, and real-time applications. These centers require massive power, cooling, and connectivity. Building them isn't just expensive—it requires rare earth minerals, advanced semiconductors, and engineering expertise concentrated in a few countries.

Europe's ambition to build a sovereign cloud stack demands tremendous investment and large-scale stockpiling of critical materials—especially if US-China tensions escalate and supply chains fracture. CSIS commentary warns that "mounting US pressure on partners to concede additional sovereign control over the tech stack could cause foreign governments and companies to rethink acquisition of a US-made tech stack."

The private sector plays a critical but conflicted role. Consortia within the ITU and World Economic Forum drive interoperable standards, but member companies also seek competitive advantage through proprietary ecosystems. Cloud providers offering customer-managed encryption keys (CMK) and bring-your-own-key (BYOK) options address sovereignty concerns—but these features also create vendor lock-in through proprietary tools, high migration costs, and data egress fees.

Africa's infrastructure deficit illustrates the stakes. With 17% of the world's population but less than 1% of colocation capacity, African nations depend on foreign providers. Data sovereignty laws create compliance requirements, but local capacity doesn't exist to meet them. Google, Amazon, and Microsoft have launched or expanded African cloud regions, but this creates new dependencies: African data may stay in Africa, but the infrastructure is owned and operated by American companies subject to US jurisdiction.

Not all approaches to digital sovereignty require hard borders. Emerging technologies offer ways to maintain control while preserving cross-border flows.

Data trusts—legal structures where trustees manage data on behalf of beneficiaries—allow sovereign control without physical localization. A European data trust could ensure EU citizen data is governed by EU law regardless of where it's processed, using contractual and technical safeguards rather than geographic restrictions.

Federated learning enables AI model training across distributed datasets without centralizing the data. Instead of moving data to the model, the model moves to the data—training locally and sharing only aggregated insights. This preserves privacy, satisfies localization requirements, and enables global collaboration. Healthcare research, financial fraud detection, and climate modeling could all benefit from cross-border data analysis without violating sovereignty.

Privacy-preserving computation—including homomorphic encryption and secure multi-party computation—allows calculations on encrypted data without decrypting it. This means sensitive information can be processed in foreign jurisdictions without exposing contents to foreign legal access.

These technologies remain nascent and face scalability challenges, but they point toward a third way: technical architectures that satisfy sovereignty concerns without fragmenting the internet.

The Cloud Security Alliance and ISO 27000 series certifications establish international standards that national regulators can adopt, creating convergence rather than fragmentation. When India requires specific security controls and Europe requires similar controls under different names, harmonizing standards reduces compliance burden while maintaining sovereign authority to audit and enforce.

For developing nations, digital sovereignty represents more than security or economics—it's about technological self-determination after generations of dependency.

The Global South AI Dialogue 2025, scheduled for later this year, explicitly frames digital sovereignty as justice: "AI frameworks are not imported prescriptions but locally-rooted architectures, built on consultative processes, indigenous knowledge, and mutually beneficial partnerships." The language is deliberate—positioning digital sovereignty against data colonialism.

The critique is sharp: Western tech companies extract data from Global South users, process it in American or European data centers, train AI models on it, then sell products back to those markets. Value flows north; dependency deepens. African countries contribute training data for facial recognition systems that don't recognize African faces accurately because development teams are predominantly Western.

South-South cooperation offers an alternative. Countries in similar developmental situations share technology, train each other's technical workforce, and negotiate collectively with global platforms. The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation's September 2025 Tianjin Declaration asserts that "all states have the sovereign right to regulate the internet within their national segments"—a direct challenge to the vision of a borderless, US-managed internet.

The African Union's Malabo Convention aims to harmonize data protection standards across the continent, easing cross-border flows within Africa while maintaining collective sovereignty vis-à-vis external actors. If successful, this regional approach could balance the benefits of scale with the imperatives of control.

But the Global South also faces a dilemma: Chinese infrastructure investment comes with strings attached. The Belt and Road Initiative funds African data centers, Southeast Asian fiber networks, and Latin American telecommunications—but often includes requirements to use Chinese equipment (Huawei, ZTE) and, increasingly, Chinese software platforms. Trading dependence on American tech giants for dependence on Chinese state-adjacent companies may not constitute true sovereignty.

Digital services are projected to reach $11.7 trillion by 2032—twice the growth rate of goods trade. This makes internet governance a central economic battleground.

Free trade agreements increasingly include digital chapters, but they fragment rather than unify. The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) commits members to liberal data flows but includes national security exceptions that countries invoke expansively. The US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) contains similar provisions with similar loopholes.

The problem: security exceptions give states the power to justify data controls for geopolitical reasons, then invoke security to shield these decisions from trade dispute mechanisms. What one country calls essential security, another calls protectionism—and trade agreements provide no objective standard to distinguish them.

The WTO's Joint Statement Initiative on Electronic Commerce, supported by 82 members representing over 90% of global trade, aims to create multilateral rules. But progress is glacial, and major economies including India and Indonesia have refused to participate, arguing that digital trade rules should prioritize development goals over market access.

Digital services taxes exemplify the collision between sovereignty and globalization. France, the UK, Italy, India, and others have imposed taxes on tech companies' local revenue—often explicitly targeting American firms. The US responded with trade threats, and negotiations produced fragile compromises that satisfy nobody. These taxes serve dual purposes: generating revenue from undertaxed digital giants and demonstrating that global platforms aren't beyond national reach.

The EU's Digital Omnibus initiative, launched September 15, 2025, seeks to simplify data, cybersecurity, and AI legislation—acknowledging that regulatory complexity itself has become a barrier. But simplification within Europe doesn't reduce fragmentation globally; it may actually deepen it by creating a more coherent European regulatory bloc that diverges further from American market-driven approaches and Chinese state-driven models.

The trajectory of digital sovereignty will shape technology, commerce, and freedom for decades. Three scenarios seem possible:

Fragmentation: The internet continues splintering into incompatible regional networks. Chinese citizens access a state-curated ecosystem. Europeans navigate strict privacy rules and limited platform features. Americans enjoy permissive platforms with pervasive surveillance capitalism. The Global South fragments further, with some nations adopting Chinese censorship tools, others emulating European regulation, and still others creating hybrid models. Cross-border innovation collapses under compliance costs. Global tech companies become regional players. The internet becomes internets—plural, disconnected, diminished.

Convergence: Facing impossible compliance burdens, governments negotiate international frameworks that harmonize essential requirements while preserving sovereign authority. Privacy-preserving technologies enable cross-border data flows without sacrificing control. Mutual legal assistance treaties streamline law enforcement access across jurisdictions. The UN Convention Against Cybercrime, despite criticisms about enabling authoritarian surveillance, establishes baseline norms that most nations accept. Cloud certifications (ISO 27000, SOC 2, FedRAMP equivalents) create common standards. The internet remains fragmented but interoperable—like international aviation, which operates under global standards while respecting national sovereignty.

Dominance: One model wins decisively. Perhaps American tech giants prove too valuable to exclude, and governments accept dependence in exchange for innovation. Perhaps China's Belt and Road infrastructure investments lock developing nations into Beijing-aligned systems. Perhaps Europe's regulatory approach becomes so commercially successful—building trusted digital ecosystems that attract users and investment—that other regions adopt it voluntarily. Perhaps a new actor emerges: India's developer talent, African demographic growth, or a Latin American regulatory innovation creates an unexpected fourth pole.

Each scenario has advocates. Fragmentation appears most likely based on current trends—but convergence may become economically necessary, and dominance can't be ruled out given how quickly digital landscapes shift.

Digital sovereignty transforms abstract policy debates into practical reality:

For businesses: Compliance is now a core competency, not an afterthought. Companies need legal expertise across jurisdictions, technical architectures that can satisfy conflicting requirements, and strategic clarity about which markets justify compliance costs. Hybrid multi-cloud strategies—keeping sovereignty-sensitive workloads local while leveraging global platforms for less-regulated activities—balance compliance with scalability. Early investment in privacy-preserving technologies and internationally recognized certifications reduces future adaptation costs.

For consumers: Your digital experience increasingly depends on where you're located. Services available in one country may be blocked, limited, or heavily modified in another. VPNs and circumvention tools work—until they don't. Understanding your nation's data protection laws and exercising available rights (access, deletion, portability) becomes essential digital literacy. Choosing services based on privacy, security, and jurisdictional protections—not just features and price—may determine whether your data remains yours.

For policymakers: The challenge is balancing legitimate sovereignty with the enormous benefits of connectivity. Overly restrictive rules kill innovation and impose costs on domestic industries. Insufficient rules leave citizens vulnerable to foreign surveillance and platform manipulation. Smart policy distinguishes genuine security requirements from protectionism, adopts international standards where they exist, and invests in domestic technical capacity rather than just mandating localization. The goal should be sovereign capability, not isolation.

For technologists: Architectural decisions now carry geopolitical weight. Designing systems with data minimization, end-to-end encryption, federation, and user control isn't just good engineering—it's survival strategy in a fragmenting world. Technologies that enable sovereignty without silos will command premium value.

The September 2025 Great Firewall leak crystallized what many suspected: we've entered an era where the internet is treated not as a global commons but as contested territory. China exports censorship infrastructure. Europe wields regulation as a weapon. India balances openness with strategic control. America watches its tech giants face restriction after restriction while arguing for free data flows that increasingly feel like arguments for American dominance.

The question isn't whether digital sovereignty will continue—it will. The question is whether it produces fragmented incompatible networks that strangle innovation, or whether humanity can forge frameworks that respect sovereign authority while preserving the collaboration and creativity that made the internet revolutionary.

That outcome depends on choices made in the next few years: technical standards adopted or rejected, trade agreements negotiated or abandoned, infrastructure investments made or deferred, and technologies developed or suppressed.

One thing is certain: the borderless internet is dead. The battle now is over what replaces it—and whether that successor will serve billions of humans or the dozens of governments claiming dominion over them. The next decade will determine whether digital sovereignty means freedom to govern our digital lives, or simply a high-tech return to medieval fiefdoms with servers instead of castles and algorithms instead of lords.

The net is fragmenting. How we put it back together—or whether we do—defines the digital age ahead.

Recent breakthroughs in fusion technology—including 351,000-gauss magnetic fields, AI-driven plasma diagnostics, and net energy gain at the National Ignition Facility—are transforming fusion propulsion from science fiction to engineering frontier. Scientists now have a realistic pathway to accelerate spacecraft to 10% of light speed, enabling a 43-year journey to Alpha Centauri. While challenges remain in miniaturization, neutron management, and sustained operation, the physics barriers have ...

Epigenetic clocks measure DNA methylation patterns to calculate biological age, which predicts disease risk up to 30 years before symptoms appear. Landmark studies show that accelerated epigenetic aging forecasts cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and neurodegeneration with remarkable accuracy. Lifestyle interventions—Mediterranean diet, structured exercise, quality sleep, stress management—can measurably reverse biological aging, reducing epigenetic age by 1-2 years within months. Commercial ...

Data centers consumed 415 terawatt-hours of electricity in 2024 and will nearly double that by 2030, driven by AI's insatiable energy appetite. Despite tech giants' renewable pledges, actual emissions are up to 662% higher than reported due to accounting loopholes. A digital pollution tax—similar to Europe's carbon border tariff—could finally force the industry to invest in efficiency technologies like liquid cooling, waste heat recovery, and time-matched renewable power, transforming volunta...

Humans are hardwired to see invisible agents—gods, ghosts, conspiracies—thanks to the Hyperactive Agency Detection Device (HADD), an evolutionary survival mechanism that favored false alarms over fatal misses. This cognitive bias, rooted in brain regions like the temporoparietal junction and medial prefrontal cortex, generates religious beliefs, animistic worldviews, and conspiracy theories across all cultures. Understanding HADD doesn't eliminate belief, but it helps us recognize when our pa...

The bombardier beetle has perfected a chemical defense system that human engineers are still trying to replicate: a two-chamber micro-combustion engine that mixes hydroquinone and hydrogen peroxide to create explosive 100°C sprays at up to 500 pulses per second, aimed with 270-degree precision. This tiny insect's biochemical marvel is inspiring revolutionary technologies in aerospace propulsion, pharmaceutical delivery, and fire suppression. By 2030, beetle-inspired systems could position sat...

The U.S. faces a catastrophic care worker shortage driven by poverty-level wages, overwhelming burnout, and systemic undervaluation. With 99% of nursing homes hiring and 9.7 million openings projected by 2034, the crisis threatens patient safety, family stability, and economic productivity. Evidence-based solutions—wage reforms, streamlined training, technology integration, and policy enforcement—exist and work, but require sustained political will and cultural recognition that caregiving is ...

Every major AI model was trained on copyrighted text scraped without permission, triggering billion-dollar lawsuits and forcing a reckoning between innovation and creator rights. The future depends on finding balance between transformative AI development and fair compensation for the people whose work fuels it.