The Renting Trap: Wealth Extraction from Working Families

TL;DR: Governments are racing to establish cognitive liberty laws protecting mental privacy as brain-reading technology moves from labs to workplaces and consumer devices. Colorado, Chile, and the EU lead efforts to regulate neural data collection before widespread adoption makes control impossible.

By 2030, neurotechnology could be as common as smartphones. Brain-reading devices are already leaving research labs and entering workplaces, classrooms, and living rooms. The question isn't whether these technologies will become mainstream, but whether your mental privacy will survive their arrival. Right now, a handful of pioneering governments are racing to answer that question with something unprecedented: cognitive liberty laws that treat your thoughts as sacred, protected territory.

For decades, brain-computer interfaces belonged to science fiction and medical research. Then everything changed. In 2024, Colorado became the first U.S. state to pass comprehensive neural data protection laws, classifying brain activity as the most sensitive personal data imaginable. Chile went even further, amending its constitution to protect "mental integrity" as a fundamental right. The European Union embedded cognitive liberty protections into its AI Act, banning systems that manipulate human decision-making through subliminal techniques.

These weren't reactions to hypothetical threats. They were responses to a reality already unfolding: employers using EEG headbands to monitor worker attention, consumer devices tracking meditation states, researchers developing brain implants that could eventually decode inner speech. The technology arrived faster than anyone expected, and lawmakers realized they needed to draw lines before those lines became impossible to draw.

The path to today's cognitive liberty debate mirrors earlier technological upheavals. When printing presses democratized information in the 1400s, authorities panicked about losing control over what people could read and think. The response was censorship, licensing, and book burning. Eventually, societies recognized that freedom of thought required freedom of information, leading to First Amendment protections and similar rights worldwide.

The internet era brought a new test. Early digital privacy laws focused on what you typed, clicked, and purchased. Nobody imagined technology could one day monitor what you think. Even as recently as 2010, brain-computer interfaces required massive equipment, surgical implants, and teams of neuroscientists to decode the simplest mental commands.

Then the miniaturization revolution hit neurotechnology. Consumer EEG headsets became affordable. Machine learning algorithms got exponentially better at interpreting neural signals. Companies like Neuralink and Precision Neuroscience received FDA clearance for brain implants with thousands of electrodes, capable of recording neural activity at unprecedented resolution. What once required a lab now fits in a headband you can order online.

Medical applications drove much of this progress. Paralyzed patients gained the ability to control robotic arms through thought. People with ALS could type by thinking about letters. Brain implants offered hope for treating depression, anxiety, and neurological disorders. The benefits were undeniable, but so was the privacy nightmare lurking beneath.

Modern neurotechnology operates on a simple but profound principle: your thoughts generate electrical patterns, and those patterns can be measured, recorded, and increasingly, decoded. Non-invasive devices like EEG headsets detect brainwaves through your scalp. More advanced systems like Neuralink's implants place electrodes directly on or in brain tissue, capturing signals with far greater precision.

Current devices can't read your thoughts like a book, but they don't need to. They can detect emotional states, attention levels, cognitive load, and decision-making patterns. Workplace monitoring systems already use this capability to track whether employees are focused or distracted. Consumer meditation apps monitor your stress levels. Gaming companies experiment with interfaces that respond to your mental state.

The trajectory is clear: as algorithms improve, so will the ability to extract meaning from neural signals. Researchers have already demonstrated systems that can reconstruct images people are viewing, predict decisions before people consciously make them, and even decode certain types of inner speech. These remain research prototypes, but the gap between laboratory and marketplace keeps shrinking.

Brain implants represent the frontier. Precision Neuroscience's FDA-cleared device uses 1,024 electrodes thinner than a human hair. Neuralink's system promises even higher bandwidth. These aren't crude sensors anymore - they're sophisticated data collection systems with direct access to your neural activity. Once that data exists in digital form, it becomes subject to all the vulnerabilities of any other data: hacking, subpoenas, corporate surveillance, and mission creep.

Colorado's HB24-1058 established neural data as sensitive biological information requiring the highest level of protection. Companies must obtain explicit consent before collecting brain data, disclose how it will be used, and face strict limits on selling or sharing it. The law treats neural information differently from other biometrics because brain activity reveals not just identity but mental states, thoughts, and potentially intentions.

California followed by expanding its Consumer Privacy Act to cover neural data. Minnesota and Montana introduced similar bills. The legislative pattern is spreading: treat cognitive data as fundamentally different from other personal information because it represents the last frontier of privacy - the contents of your mind.

Chile's approach went deeper, enshrining "neurorights" into its constitution. The amendment protects mental privacy, personal identity, free will, and equitable access to cognitive enhancement technologies. It's a recognition that as neurotechnology advances, the very concepts of self and autonomy need legal protection. You can't have freedom of thought if your thoughts aren't private.

The EU's AI Act takes a different angle, focusing on manipulative uses of neurotechnology. It bans AI systems that deploy subliminal techniques to manipulate behavior, exploit vulnerabilities based on mental state, or interfere with cognitive liberty without informed consent. The emphasis is on preventing harm before it happens, rather than just regulating data collection.

Together, these laws create the beginnings of a cognitive liberty framework: your brain data is yours, you must consent to its collection, companies can't manipulate your mental states without permission, and you have the right to mental privacy as a fundamental human right.

The workplace is where cognitive liberty theory meets uncomfortable reality. Some companies already deploy brain-monitoring wearables to track employee focus and productivity. Drivers wear EEG-equipped caps that alert managers when attention wanes. Office workers use headbands that monitor cognitive load and suggest breaks.

Employers argue these tools improve safety and performance. Nobody wants a drowsy truck driver or a distracted air traffic controller. Brain monitoring could catch dangerous lapses before they cause accidents. It could optimize work schedules around individual cognitive rhythms. In theory, it's a win-win: workers perform better, employers reduce accidents and costs.

But the power imbalance is stark. Workers who refuse monitoring risk losing jobs or opportunities. Once the technology exists, economic pressure drives adoption regardless of individual comfort. And scope creep is inevitable: systems marketed for safety monitoring get repurposed for productivity surveillance, performance reviews, or identifying "disengaged" employees.

Current cognitive liberty laws address this by requiring consent and limiting use cases. Colorado's law prohibits using neural data for employment decisions without explicit permission. But enforcement is tricky. How do you prove your brain data influenced a promotion decision? How do workers genuinely consent when employment depends on compliance? The laws create rights on paper that may be difficult to exercise in practice.

Consumer neurotechnology raises different concerns. Meditation apps and focus-enhancing headsets promise to optimize your mental state. Gaming interfaces adapt to your emotional responses. Marketing firms explore neuromarketing techniques that measure brain responses to advertisements, products, and brand messaging.

The appeal is genuine. Neurofeedback can help treat ADHD, anxiety, and sleep disorders without medication. Brain-responsive interfaces could make technology more intuitive and accessible. Understanding how your brain reacts to stimuli offers insights into your own mental patterns.

But once you generate neural data through consumer devices, that information becomes a commodity. Companies collect it, analyze it, and potentially sell it. Your brain's response patterns could inform personalized advertising, predict your purchasing behavior, or reveal information you never intended to share. Privacy concerns in consumer neurotechnology aren't theoretical - they're active research areas because the risks are already materializing.

Cognitive liberty laws aim to give consumers control. Before a company can collect your brain data, they must explain what they're collecting, how they'll use it, and who they might share it with. You have the right to access your own neural data and request its deletion. These are extensions of existing privacy rights, adapted for neurotechnology's unique intimacy.

The challenge is enforcement. Consumer EEG devices often connect to smartphones, blending neural data with other information streams. Companies can claim they're collecting "usage data" or "device performance metrics" while actually monitoring your mental states. The technical complexity makes meaningful consent difficult - most users can't realistically evaluate what brain data reveals or how it might be misused.

Brain implants for medical purposes occupy the most complex space in cognitive liberty debates. Patients with neurological conditions see these devices as life-changing - restoring communication, mobility, or relief from debilitating symptoms. For them, cognitive liberty includes the right to access brain-enhancing technologies, not just protection from surveillance.

This creates tension. Strict privacy rules could slow medical innovation or make neurotechnology prohibitively expensive. Requiring detailed consent disclosures might confuse vulnerable patients. Limiting data collection could reduce device effectiveness - many implants improve through machine learning on patient neural data.

But medical devices also present unique risks. Therapeutic brain implants connect to external systems for programming and monitoring. That connectivity creates security vulnerabilities. Hackers could potentially access patient neural data or, more frighteningly, alter device settings. A breach of mental privacy from a medical device carries different stakes than a consumer gadget leak.

Cognitive liberty laws typically carve out medical exceptions while maintaining core protections. Informed consent requirements become more detailed. Security standards get stricter. Patient rights to access and control their neural data remain, but with recognition that medical necessity sometimes overrides convenience.

The medical context also highlights the "right to cognitive enhancement" dimension. If brain implants can restore lost function, should healthy people access them for enhancement? If neurofeedback improves focus, should it be available only by prescription? Cognitive liberty includes not just freedom from mental surveillance but also freedom to modify your own cognition - within limits that societies are still defining.

Brain data as evidence represents cognitive liberty's hardest test. If neural activity could prove guilt or innocence, should courts allow it? If brain scans could detect lies more accurately than polygraphs, would that justify mandatory testing? Law enforcement sees investigative potential; civil liberties advocates see Orwellian nightmare fuel.

Current neurotechnology can't read guilt or innocence from brain scans. But it can detect recognition, emotional responses, and stress indicators. These might not reveal what you did, but they could show what you know. That's enough to interest investigators, especially as techniques improve.

Cognitive liberty frameworks generally extend Fifth Amendment-style protections to neural data. You can't be compelled to incriminate yourself through brain activity monitoring. Prosecutors need warrants to access neural data, just as they need warrants for other private information. These protections treat your mental contents as the ultimate form of self-incrimination - thoughts you haven't chosen to express.

But exceptions exist. Public safety emergencies might justify neural monitoring. Convicted criminals could face brain-based monitoring as a condition of parole. The challenge is preventing narrow exceptions from becoming normalized practice. Once law enforcement can access neural data in some cases, pressure builds to expand those cases. The infrastructure created for legitimate purposes becomes available for mission creep.

While Colorado and Chile lead legislative efforts, other jurisdictions watch closely. Mexico introduced neurorights into its Charter of Digital Rights. Brazil considers similar measures. The United Nations Human Rights Council passed a resolution recognizing mental privacy as a human right, signaling international awareness.

Yet consensus remains elusive. Technology companies worry that strict regulations will stifle innovation or fragment global markets. Countries with less democratic governance see neurotechnology as a tool for control rather than an arena for rights protection. The result is a patchwork of approaches ranging from comprehensive protection to virtually no oversight.

This fragmentation creates problems. Neural data collected under one jurisdiction's rules might be processed under another's. Companies could jurisdiction-shop, basing neurotechnology operations in countries with minimal regulation. Individuals in countries without cognitive liberty laws have no recourse when their mental privacy gets violated. A global challenge needs global coordination, but nationalism and competing interests make that coordination difficult.

The UN resolution represents a starting point, but international law moves slowly. By the time comprehensive treaties emerge, neurotechnology could be so embedded in daily life that meaningful regulation becomes nearly impossible. That's why advocates push for domestic laws now - establishing principles before the technology becomes too entrenched to govern effectively.

Individual action can't replace systematic regulation, but it's not meaningless either. Start by auditing neurotechnology in your life. Do you use apps or devices that monitor brain activity, even indirectly through sleep tracking or meditation tools? Read their privacy policies, focusing on data collection, retention, and sharing practices. Most won't be transparent, but asking the question matters.

If your employer introduces workplace brain monitoring, understand your rights under state law. Colorado residents can refuse consent for neural data collection in employment contexts. Even in states without specific protections, questioning the purpose, security, and scope of monitoring can prompt reconsideration. Collective worker action is more effective than individual refusal.

Advocate for cognitive liberty laws where you live. State-level legislation is often more achievable than federal action. Contact representatives, support privacy advocacy organizations, and make mental privacy a voting issue. Lawmakers respond to constituent pressure, especially on emerging issues where positions haven't hardened.

Support neurotechnology research and medical applications while demanding privacy protections. These aren't contradictory goals. Advocating for cognitive liberty doesn't mean opposing brain-computer interfaces - it means ensuring they develop with mental privacy built in, not bolted on later. Privacy-preserving neurotechnology is technically feasible; market incentives and regulations determine whether it becomes standard.

Current cognitive liberty laws, pioneering as they are, leave significant holes. Most cover only explicit neural data collection through brain-monitoring devices. They don't address indirect mental state inference through behavioral tracking, keystroke analysis, or AI-powered prediction systems. If a company can deduce your mental state from patterns without directly reading your brain, many cognitive liberty protections don't apply.

Enforcement remains weak. State laws impose penalties for neural data violations, but proving misuse is difficult. Neural data breaches might not be immediately obvious. By the time violations surface, damage is done. And laws focused on data privacy don't address manipulative uses - systems designed to influence decision-making through perfectly legal means.

The medical device exception could become a loophole. If brain implants marketed for therapy collect extensive neural data, companies might argue medical necessity justifies collection far beyond treatment needs. The data gathered for medical purposes could be repurposed for research, sold to aggregators, or accessed by insurers. Medical framing doesn't automatically make collection benign.

International coordination is perhaps the biggest gap. Without global standards, neurotechnology development will migrate to jurisdictions with minimal oversight. Neural data collected abroad might flow to countries with stronger protections, undermining those protections. Digital rights don't respect borders; cognitive liberty laws need to account for that reality.

Federal legislation is in the works. Senators Cantwell, Schumer, and Markey introduced the Neural Data Protection Act, which would establish national standards for cognitive liberty. The bill faces uncertain prospects in a divided Congress, but its introduction signals mainstream political recognition of the issue.

Advocates push for stronger provisions: presumptive bans on workplace neural monitoring, prohibition of neural data sales, stricter security requirements for brain-interfacing devices, and treating cognitive manipulation as illegal regardless of technology used. These would go beyond current state laws, establishing cognitive liberty as a fundamental right rather than a privacy subclass.

Opposition comes from predictable sources. Technology companies want flexibility to innovate. Business groups fear litigation and compliance costs. Even medical researchers worry that overregulation might delay life-saving treatments. These concerns aren't entirely unfounded - poorly designed rules could cause real harm.

The question is whether we can protect cognitive liberty while allowing beneficial neurotechnology to flourish. History suggests the answer is yes, but only if we establish rights early and defend them consistently. Digital privacy initially had few protections. Decades of advocacy, litigation, and legislation gradually built the framework we have today. Cognitive liberty needs to move faster because neurotechnology advances at digital speed.

Within your lifetime, brain-reading technology could become as ubiquitous as fingerprint scanners. The question isn't whether that future arrives, but what rules govern it. Right now, in Colorado hearing rooms, Chilean congressional chambers, and EU regulatory offices, the foundations of cognitive liberty are being laid. These laws might seem abstract, but they'll determine whether your thoughts remain yours.

Pay attention. This isn't a distant science fiction concern. Consumer neurotechnology is already on the market. Workplace brain monitoring pilots are running. Medical implants with unprecedented neural access are earning regulatory approval. The infrastructure for reading brain activity is being built right now, and the rules being written today will shape how that infrastructure gets used for decades.

Your mental privacy is on the line. Cognitive liberty laws offer protection, but only if they're comprehensive, enforceable, and internationally coordinated. That requires public awareness and political pressure. The race to protect your thoughts isn't theoretical anymore - it's happening, and your participation might determine whether your mind remains the one place no one else can access without permission.

The frontier of digital rights has shifted inward, to the last private space: your thoughts. What happens next depends on whether we recognize that frontier in time to defend it.

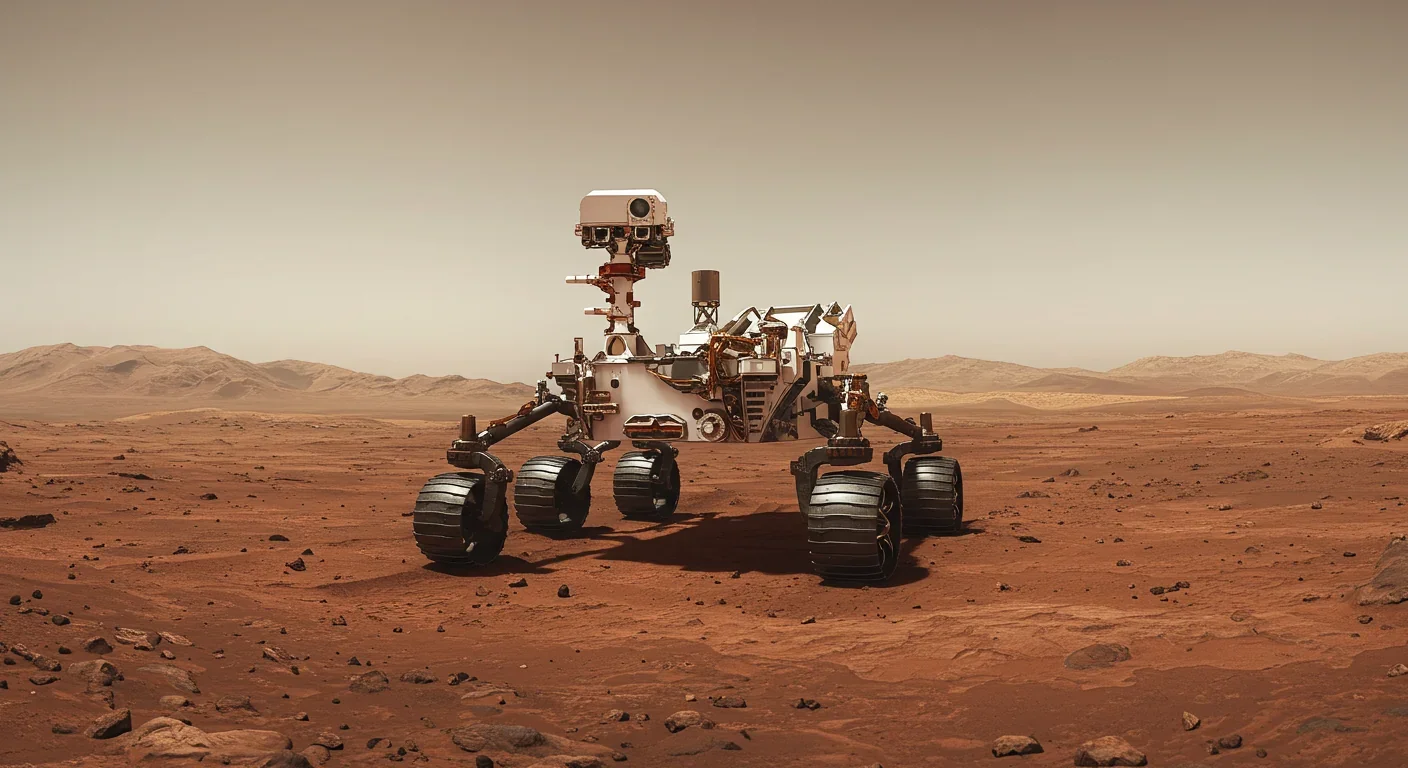

Curiosity rover detects mysterious methane spikes on Mars that vanish within hours, defying atmospheric models. Scientists debate whether the source is hidden microbial life or geological processes, while new research reveals UV-activated dust rapidly destroys the gas.

CMA is a selective cellular cleanup system that targets damaged proteins for degradation. As we age, CMA declines—leading to toxic protein accumulation and neurodegeneration. Scientists are developing therapies to restore CMA function and potentially prevent brain diseases.

Intercropping boosts farm yields by 20-50% by growing multiple crops together, using complementary resource use, nitrogen fixation, and pest suppression to build resilience against climate shocks while reducing costs.

The Baader-Meinhof phenomenon explains why newly learned information suddenly seems everywhere. This frequency illusion results from selective attention and confirmation bias—adaptive evolutionary mechanisms now amplified by social media algorithms.

Plants and soil microbes form powerful partnerships that can clean contaminated soil at a fraction of traditional costs. These phytoremediation networks use biological processes to extract, degrade, or stabilize toxic pollutants, offering a sustainable alternative to excavation for brownfields and agricultural land.

Renters pay mortgage-equivalent amounts but build zero wealth, creating a 40x wealth gap with homeowners. Institutional investors have transformed housing into a wealth extraction mechanism where working families transfer $720,000+ over 30 years while property owners accumulate equity and generational wealth.

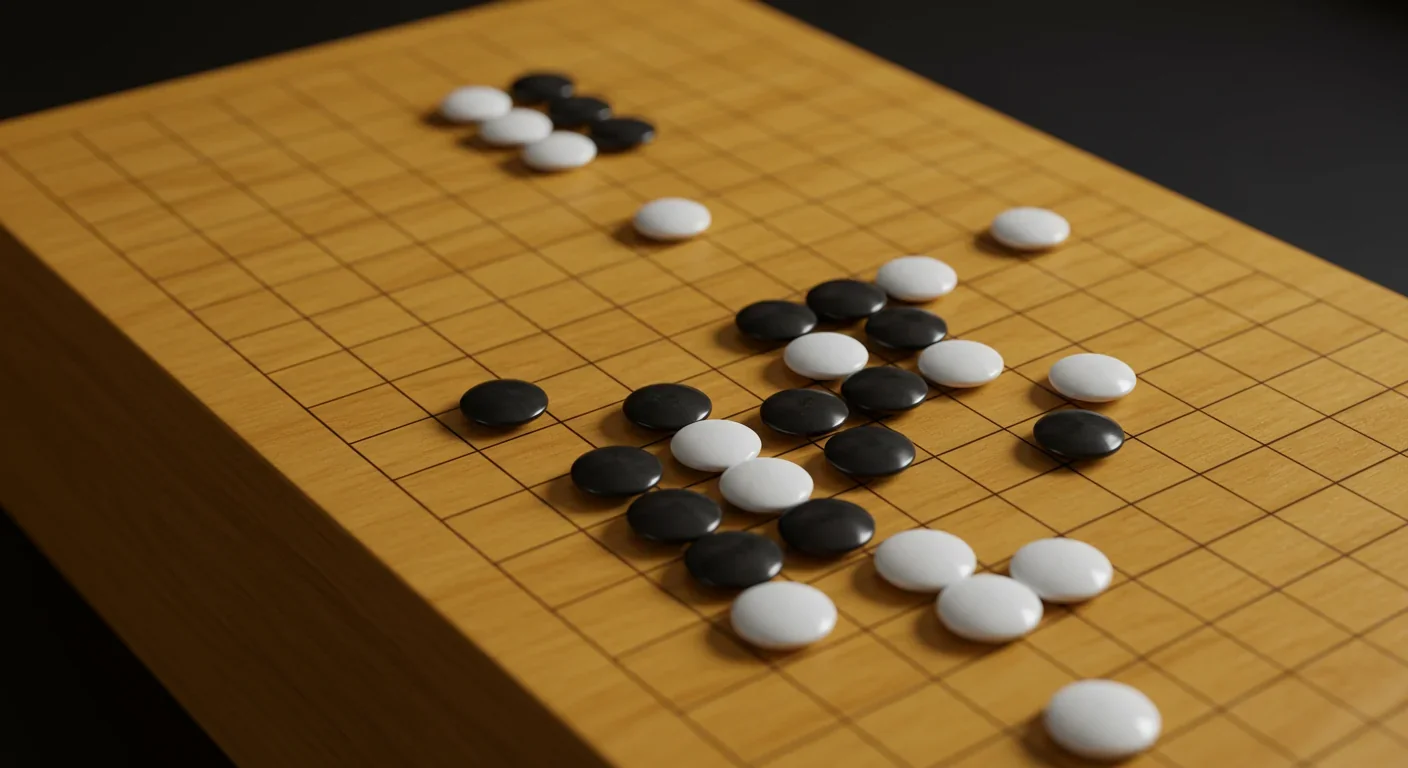

AlphaGo revolutionized AI by defeating world champion Lee Sedol through reinforcement learning and neural networks. Its successor, AlphaGo Zero, learned purely through self-play, discovering strategies superior to millennia of human knowledge—opening new frontiers in AI applications across healthcare, robotics, and optimization.