The Curse of Knowledge: Why Experts Can't Teach Beginners

TL;DR: The Baader-Meinhof phenomenon explains why newly learned information suddenly seems everywhere. This frequency illusion results from selective attention and confirmation bias—adaptive evolutionary mechanisms now amplified by social media algorithms.

You learn a new word, and suddenly you hear it in every conversation. You notice someone's unique car model, and now you see it on every street corner. A friend mentions an obscure band, and their songs seem to play wherever you go. It feels like reality itself has shifted to accommodate your newfound awareness. But here's the catch: nothing in the world has actually changed—only your brain has.

This uncanny experience has a name: the Baader-Meinhof phenomenon, also called the frequency illusion. It's a cognitive bias that makes recently learned information seem startlingly omnipresent, as if the universe is conspiring to show you the same thing repeatedly. The phenomenon reveals something profound about how your brain filters an overwhelming torrent of information—and how this ancient survival mechanism can mislead you in modern life.

The term "Baader-Meinhof phenomenon" has a peculiar origin story that's almost as interesting as the cognitive bias itself. In 1994, Terry Mullen wrote a letter to the St. Paul Pioneer Press newspaper describing his experience: after hearing about the Baader-Meinhof Gang—a German terrorist group from the 1970s—for the first time, he encountered references to it twice more within 24 hours. The newspaper published his letter, and the catchy name stuck, eventually spreading across the internet and becoming the most popular term for this well-documented cognitive quirk.

The phenomenon itself predates the name by millennia. What Mullen experienced, and what you've likely experienced countless times, is rooted in fundamental mechanisms of human attention and memory. Scientists prefer the more descriptive term "frequency illusion," but the Baader-Meinhof label captures the eerie, almost supernatural quality of the experience.

To understand why new information seems to multiply before your eyes, you need to understand how your brain handles the overwhelming flood of sensory data it encounters every moment. Right now, your nervous system is processing millions of bits of information—the texture of your clothing, distant sounds, visual details, internal sensations—yet you're consciously aware of only a tiny fraction.

This filtering happens through a process called selective attention. "Selective attention is the ability to notice some things and not others," explains psychiatrist Dr. Alex Dimitriu. Think of it as a mental spotlight that illuminates certain details while leaving others in darkness. Without this capability, you'd be paralyzed by information overload, unable to function in a world that bombards you with more stimuli than your conscious mind could ever process.

Your brain processes millions of bits of information every second, but you're only consciously aware of a tiny fraction—selective attention acts as a mental spotlight, determining what breaks through to your awareness.

A key player in this filtering system is the reticular activating system (RAS), a network of neurons in your brainstem that acts as a gatekeeper between your subconscious and conscious awareness. The RAS evolved to help our ancestors survive by prioritizing information relevant to immediate needs—food, threats, mating opportunities. When you learn something new or designate something as important, your RAS essentially gets programmed to flag similar information, making it break through into your conscious awareness.

This is where the frequency illusion begins. Once you've noticed something—a red Volkswagen Beetle, the word "serendipity," or news about artificial intelligence—your RAS marks it as significant. Suddenly, instances that were always present in your environment but previously filtered out now demand your attention. The red Beetles were always on the road. The word "serendipity" was always in articles and conversations. AI news was always in your feed. You just weren't noticing them because your brain's spotlight was pointing elsewhere.

Selective attention opens the door to the frequency illusion, but another cognitive mechanism kicks it wide open: confirmation bias. This is your brain's tendency to seek out, interpret, and remember information that supports what you already believe or expect.

Here's how it amplifies the frequency illusion: Once you've noticed something a few times, you unconsciously start forming a hypothesis—"This thing is everywhere now." Your brain then actively looks for evidence supporting this belief while ignoring or downplaying contradictory evidence. You notice every red Beetle but don't register the dozens of blue Hondas, silver Toyotas, and black Fords you pass. You remember the three times someone said "serendipity" but forget the hundreds of other words they used.

"You see something a few times, then you start to notice it more, and then you start to find ways to confirm it's the only truth."

— Joseph Vacchiano, LCSW

Joseph Vacchiano, a licensed clinical social worker, describes the phenomenon as a self-reinforcing cycle: "You see something a few times, then you start to notice it more, and then you start to find ways to confirm it's the only truth." This feedback loop creates an illusion so convincing that most people never question whether the pattern is real or imagined.

Research by psychologists Begg, Anas, and Farinacci in 1986 demonstrated how this works experimentally. They found that people's frequency estimates for words weren't based on actual repetition but on contextual variety and semantic associations. In other words, your brain isn't accurately counting occurrences—it's constructing a narrative based on salience and emotional significance.

The frequency illusion might sound like a design flaw in human cognition, but it's actually a feature, not a bug. From an evolutionary perspective, this bias has kept our species alive for hundreds of thousands of years.

The natural frequency hypothesis, proposed by psychologists Gigerenzer and Hoffrage, suggests that humans evolved to process information in terms of frequencies rather than single-event probabilities. Our hunter-gatherer ancestors didn't have time for statistical analysis when deciding whether a rustling in the bushes meant danger. Those who quickly recognized patterns—even false ones—and acted on them had better survival odds than those who waited for more data.

Spotting patterns quickly meant noticing when edible berries appeared in a certain area, when predators tended to hunt, or when weather patterns shifted. Better to overestimate the frequency of important events and be wrong occasionally than to underestimate them and face dire consequences. In this context, the frequency illusion is a form of adaptive paranoia—a hair-trigger response that values quick pattern recognition over perfect accuracy.

This explains why the availability heuristic plays such a strong role in the frequency illusion. Events that are recent, vivid, or emotionally charged become "available" in memory, making them feel more frequent or probable than they actually are. If you recently heard about a plane crash, you'll overestimate the danger of flying, even though statistically it's safer than driving. Your brain prioritizes memorable information over statistical reality because in ancestral environments, memorable usually meant important.

The problem, of course, is that modern life doesn't work like the African savanna. The stimuli we encounter today—brands, news stories, social media trends—rarely pose life-or-death stakes. Yet our brains still treat new information with the same urgency our ancestors used for spotting predators, leading to systematic misperceptions about what's common and what's rare.

The frequency illusion belongs to a broader family of cognitive biases related to pattern recognition and apophenia—the tendency to perceive meaningful connections between unrelated things. While pattern recognition is essential for learning and problem-solving, it can misfire spectacularly when your brain finds patterns in random noise.

One closely related phenomenon is the clustering illusion, where people perceive clusters in random data that are actually consistent with a random distribution. If you flip a fair coin 100 times, you'll likely see several sequences of four or five heads in a row. Most people, however, will interpret these clusters as meaningful rather than recognizing them as statistical inevitabilities.

The recency illusion works hand-in-hand with frequency illusion, making newly noticed stimuli seem newly introduced rather than simply newly noticed. When you first hear slang like "no cap," you might think it's a brand-new phrase spreading virally. In reality, it may have been in use for years within certain communities before reaching your awareness. Your brain conflates "new to you" with "new to the world."

The frequency illusion is a feature, not a bug—it's an evolutionary adaptation that helped our ancestors survive by rapidly identifying patterns, even at the cost of occasional false positives.

Another contributor is the split-category effect, where subdividing a category increases perceived frequency. If you start distinguishing between different types of SUVs—crossovers, full-size, compact—you'll suddenly notice more SUVs on the road, not because there are more, but because you're now mentally splitting them into more categories. Each subcategory draws your attention separately, multiplying the apparent frequency.

These interconnected biases create a powerful illusion of meaning and pattern. Your brain is a meaning-making machine, constantly trying to construct coherent narratives from disparate information. When it notices something twice by chance, it automatically starts building a story about why this is happening, rather than accepting the simpler explanation: random coincidence amplified by selective attention.

If the frequency illusion was powerful in the pre-digital age, it's become supercharged in the era of social media algorithms and personalized content delivery. Modern recommendation systems don't just passively reflect your interests—they actively amplify them, creating feedback loops that make the frequency illusion feel more real than ever.

Here's how it works: You watch one video about a particular topic—say, cryptocurrency or sourdough bread. The platform's algorithm immediately interprets this as a signal of interest and starts serving you more similar content. You engage with some of these recommendations, which the algorithm takes as confirmation, leading it to double down on this content category. Within days, your feed is dominated by the topic, creating the impression that "everyone" is suddenly talking about crypto or sourdough.

What's actually happening is that the algorithm has created a personalized echo chamber that reflects your recent attention back at you. The rest of the world hasn't changed its interests—you've just been funneled into a content bubble that amplifies your initial curiosity into an apparent trend.

This algorithmic amplification has serious implications beyond just making your social media experience feel repetitive. It can distort your perception of how common or important certain issues, products, or ideas actually are. During the COVID-19 pandemic, for instance, the frequency illusion combined with algorithm-driven content delivery led some doctors to overestimate the prevalence of certain symptoms (like "COVID toes") because cases were repeatedly surfacing in their feeds and medical forums.

In the realm of consumer behavior, marketers have long understood and exploited the frequency illusion through repeated exposure strategies. But digital advertising takes this to another level. Once you search for a product—even casually—retargeting ads follow you across websites, creating the illusion that "everyone" is buying this product right now. The frequency you're observing isn't organic; it's engineered by algorithms designed to convert casual interest into purchases.

"Social media algorithms warp how people learn from each other by showing more of what you've already shown interest in, creating an artificial sense of consensus or ubiquity."

— Research from The Conversation

Research shows that social media algorithms fundamentally warp how people learn from each other. By showing you more of what you've already shown interest in, these systems create an artificial sense of consensus or ubiquity. This doesn't just affect consumer choices—it shapes political beliefs, health decisions, and social attitudes. When your feed suggests that everyone shares your newly formed opinion or concern, you're less likely to question it or seek out alternative perspectives.

The frequency illusion thrives in this environment because the algorithm actively validates your initial pattern recognition. Where once you might have noticed something a few times by chance and then gradually realized it wasn't actually everywhere, today's platforms ensure that it really does become everywhere—at least in your personalized information environment. The illusion and reality have merged.

While the frequency illusion is often harmless—making you think a new slang term is more popular than it is—it can lead to serious errors in judgment when it comes to health, finance, and risk assessment. Understanding when this bias is most likely to mislead you is crucial for making better decisions.

In medicine, the frequency illusion can lead to diagnostic errors and unnecessary treatments. When medical professionals learn about a rare condition, they may start diagnosing it in patients whose symptoms could have multiple explanations. This isn't necessarily bad—increased awareness of rare diseases can save lives when they're actually present. But it can also lead to over-diagnosis, unnecessary testing, and increased patient anxiety.

The COVID-19 pandemic provided numerous examples. Doctors who read about specific COVID symptoms in medical journals began seeing those symptoms everywhere in their practice, sometimes attributing common conditions to COVID when other explanations were more likely. The combination of heightened awareness, confirmation bias, and genuine diagnostic uncertainty created a perfect storm for frequency illusion.

In economics and investing, the frequency illusion can be financially devastating. Research with Swedish women found that when food prices rose, they perceived overall inflation as higher than it actually was, illustrating how focused attention on one category can distort perception of broader trends. Investors who recently learned about a particular company or sector may start seeing "signs" everywhere that they should invest, interpreting random news items or casual mentions as meaningful indicators.

The phenomenon also plays into conspiracy thinking and misinformation spread. Once someone encounters a conspiracy theory, they start noticing "evidence" everywhere that seems to support it—ambiguous events get interpreted as confirmation, coincidences become proof, and contradictory information gets filtered out. The frequency illusion makes the conspiracy feel more credible and widespread than it is, reinforcing belief and making it harder to change minds with facts.

Risk perception is another area where this bias leads us astray. After hearing about a dramatic event—a shark attack, a plane crash, a rare disease—people dramatically overestimate the likelihood of experiencing it themselves. This is the availability heuristic working alongside the frequency illusion: The vivid, memorable event becomes mentally "available," creating the sense that it's common, which in turn causes you to notice every related news story or mention, further amplifying the perceived risk.

Awareness is the first step toward mitigating the frequency illusion, but awareness alone won't eliminate it. These cognitive processes happen automatically, below the level of conscious control. However, there are strategies that can help you recognize when you're likely experiencing the phenomenon and adjust your thinking accordingly.

Question your pattern recognition. When you find yourself thinking, "I'm seeing this everywhere lately," pause and ask yourself: Is this actually more common now, or have I just started noticing it? Consider whether there's a plausible reason for an actual increase (a new product launch, seasonal trends, breaking news) or whether you've simply become more attuned to something that was always present.

Actively seek contradictory data. Confirmation bias is hard to overcome, but you can deliberately look for information that challenges your emerging pattern. If you think a particular car model is suddenly everywhere, spend a day consciously noting all the different car models you see. You'll likely discover that your "frequent" car is actually just one among many.

When you catch yourself thinking "I'm seeing this everywhere," pause and ask: Is this actually more common now, or have I just started noticing it? The answer is usually the latter.

Diversify your information sources. The algorithmic echo chamber makes the frequency illusion worse. Deliberately exposing yourself to diverse content, different platforms, and perspectives that challenge your recent focus can help break the feedback loop. Following accounts and sources outside your usual interests reduces the chance that one topic will dominate your feed.

Use mindfulness to notice your attention. Mindfulness practices can help you become more aware of where your attention is going and why. When you catch yourself fixating on a particular stimulus, you can consciously redirect your focus to other aspects of your environment. This doesn't eliminate selective attention—that's impossible—but it can make you more conscious of when you're in the grip of a strong attentional bias.

Delay important decisions. If you're making a significant decision based on something you recently learned or noticed—whether it's a medical diagnosis, an investment, or a belief about social trends—build in a waiting period. The intensity of the frequency illusion tends to diminish over time as your brain's initial heightened attention fades. A decision that feels urgent in the moment often looks different after a few weeks of normal attention.

Consult actual data. When it matters, look up statistics and objective measures rather than relying on your gut feeling about frequency. Is crime actually rising in your city, or are you just noticing it more after a recent incident? Are certain health issues becoming more common, or is media coverage increasing? Real data can provide a reality check against your biased perception.

The Baader-Meinhof phenomenon is more than just a curious quirk of perception—it's a window into the fundamental operations of human consciousness. It reveals that what we experience as objective reality is actually a highly filtered, interpreted construction created by our brain's attentional and memory systems.

Every moment, your brain makes thousands of decisions about what deserves your attention and what can be safely ignored. These decisions shape not just what you notice, but what you believe, how you make decisions, and how you understand the world. The frequency illusion shows you this process in action, demonstrating that your experience of "everywhere" often says more about the state of your attention than about the state of the world.

This has profound implications for how we navigate an information-saturated world. We like to think we're objective observers, rationally processing facts and drawing logical conclusions. The frequency illusion reveals that we're actually more like artists, painting impressionistic portraits of reality based on what catches our eye, with huge swaths of the canvas left blank because our attention spotlight never illuminated those areas.

Understanding this doesn't mean you can escape it—these processes are too fundamental to human cognition for that. But it does mean you can develop a healthy skepticism about your immediate perceptions and intuitions, especially when they involve frequency, prevalence, or trends. The next time something seems to suddenly be everywhere, you'll know to ask: Did the world change, or did I?

And perhaps most importantly, the Baader-Meinhof phenomenon reminds us that our minds are not passive receivers of information but active participants in creating our experienced reality. The patterns we see, the connections we make, and the stories we tell ourselves are shaped as much by our internal attention mechanisms as by external events. Recognizing this doesn't diminish the richness of human experience—it deepens our appreciation for the remarkable, if occasionally misleading, capabilities of the human mind.

The frequency illusion is everywhere once you know about it. But now you know why.

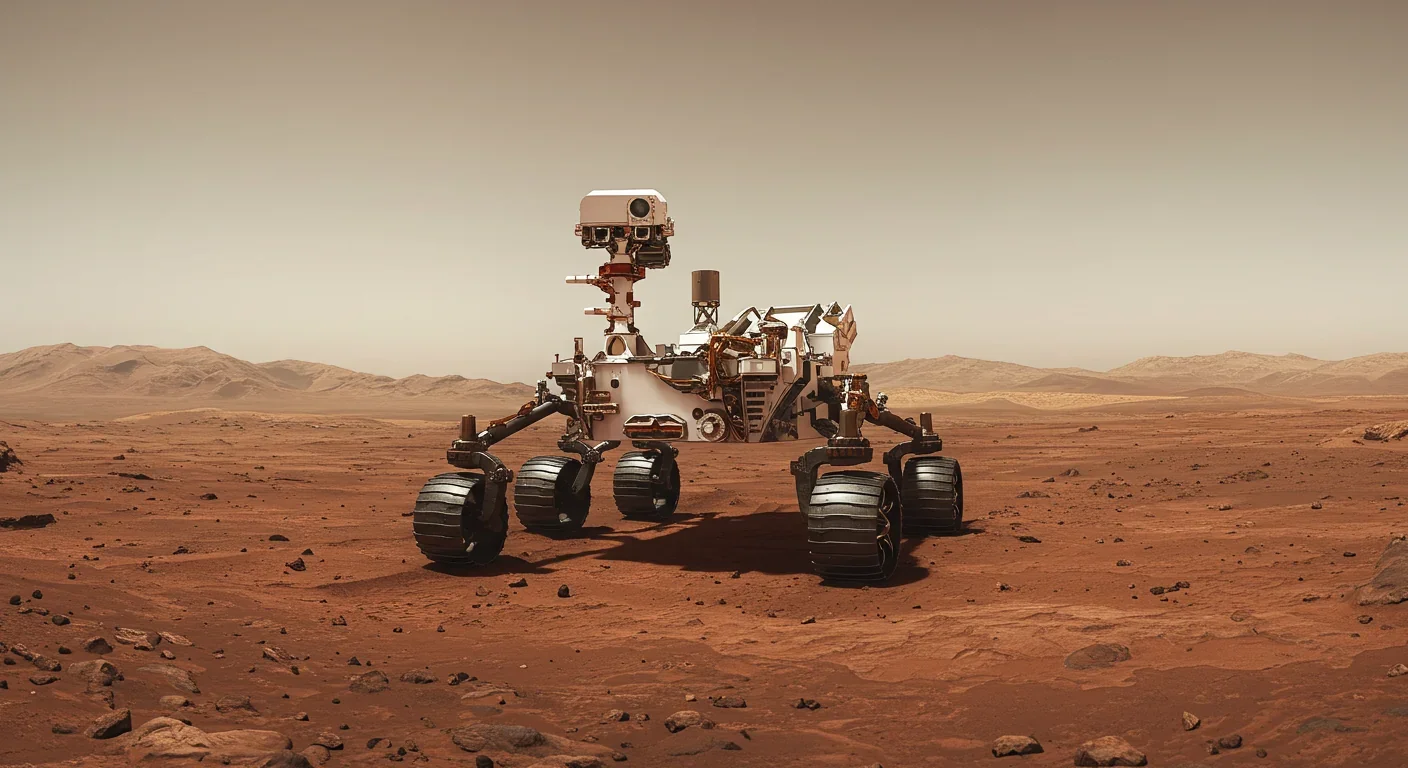

Curiosity rover detects mysterious methane spikes on Mars that vanish within hours, defying atmospheric models. Scientists debate whether the source is hidden microbial life or geological processes, while new research reveals UV-activated dust rapidly destroys the gas.

CMA is a selective cellular cleanup system that targets damaged proteins for degradation. As we age, CMA declines—leading to toxic protein accumulation and neurodegeneration. Scientists are developing therapies to restore CMA function and potentially prevent brain diseases.

Intercropping boosts farm yields by 20-50% by growing multiple crops together, using complementary resource use, nitrogen fixation, and pest suppression to build resilience against climate shocks while reducing costs.

The Baader-Meinhof phenomenon explains why newly learned information suddenly seems everywhere. This frequency illusion results from selective attention and confirmation bias—adaptive evolutionary mechanisms now amplified by social media algorithms.

Plants and soil microbes form powerful partnerships that can clean contaminated soil at a fraction of traditional costs. These phytoremediation networks use biological processes to extract, degrade, or stabilize toxic pollutants, offering a sustainable alternative to excavation for brownfields and agricultural land.

Renters pay mortgage-equivalent amounts but build zero wealth, creating a 40x wealth gap with homeowners. Institutional investors have transformed housing into a wealth extraction mechanism where working families transfer $720,000+ over 30 years while property owners accumulate equity and generational wealth.

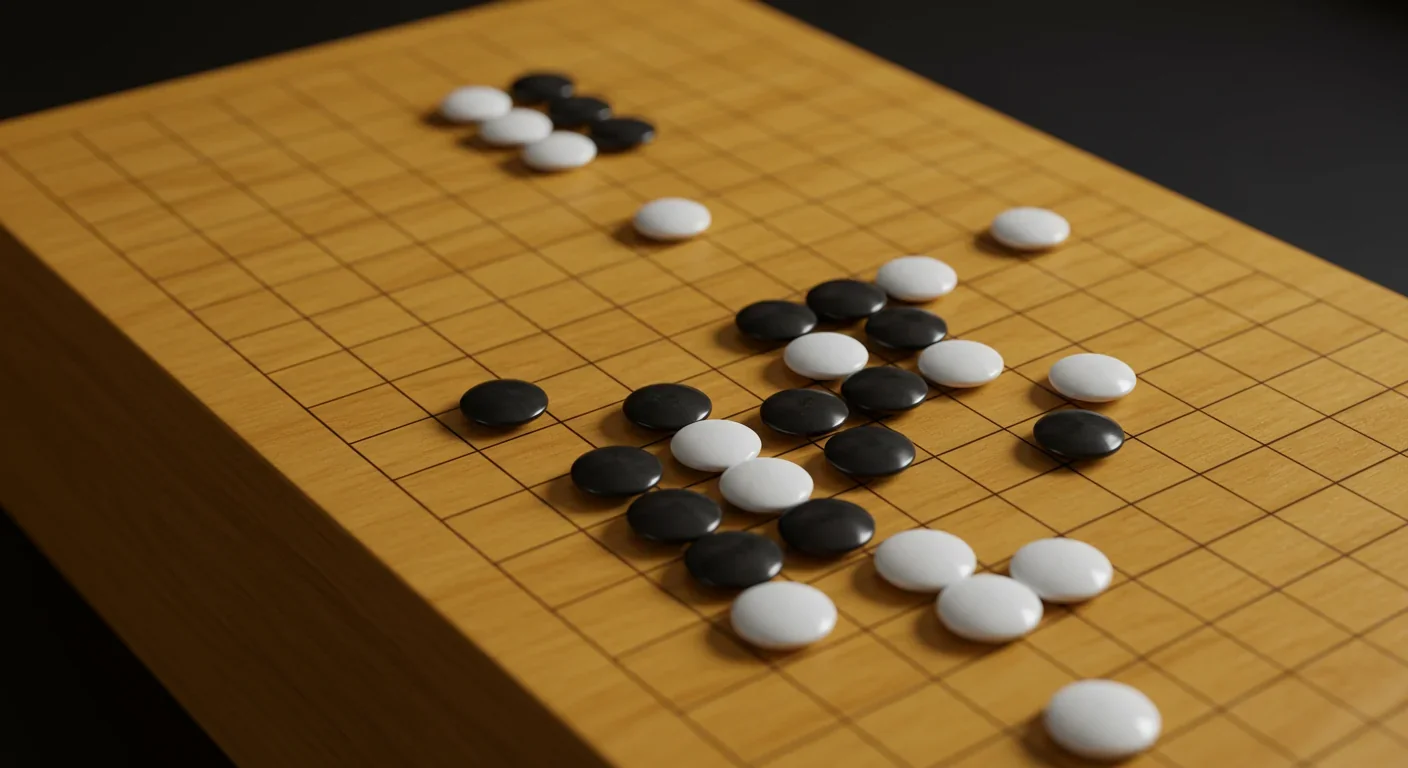

AlphaGo revolutionized AI by defeating world champion Lee Sedol through reinforcement learning and neural networks. Its successor, AlphaGo Zero, learned purely through self-play, discovering strategies superior to millennia of human knowledge—opening new frontiers in AI applications across healthcare, robotics, and optimization.