The Renting Trap: Wealth Extraction from Working Families

TL;DR: Gig companies like Uber and Lyft have fought billion-dollar legal battles to classify workers as independent contractors rather than employees, avoiding costs that could increase by 30%. Despite spending $224 million to pass California's Prop 22, promised benefits proved hollow, with drivers earning as little as $5.64/hour after expenses.

In 2004, Dynamex Operations made a quiet decision that would spark a billion-dollar legal battle: the delivery company stopped treating its drivers as employees and reclassified them all as independent contractors. The move saved money—lots of it—but opened a Pandora's box that still hasn't closed. Two decades later, that same question haunts courtrooms from California to Brussels: when does a gig worker stop being their own boss and become someone else's employee?

The answer matters more than you think. Right now, somewhere between 30 and 60 million Americans earn at least part of their income through gig platforms. Whether they're classified as employees or independent contractors determines if they get minimum wage, overtime pay, health benefits, unemployment insurance, workers' compensation, and the right to unionize. It's the difference between earning $34 per hour (what Uber claims drivers make) and $9.09 per hour after expenses (what UC Berkeley researchers actually found).

For gig companies, the stakes are even higher. Reclassifying workers as employees would increase labor costs by roughly 30 percent, adding billions in payroll taxes, insurance premiums, and benefits. That's why Uber, Lyft, and DoorDash spent over $224 million to pass a single California ballot measure protecting their business model. It became the most expensive ballot initiative in state history.

Before 2018, determining who counted as an employee involved what lawyers call the "Borello test"—a meandering checklist of factors including who supplied the tools, how people got paid, whether the relationship felt permanent, and a dozen other considerations. Courts weighed all these factors against each other, which made outcomes unpredictable and gave companies plenty of wiggle room.

Then came Dynamex Operations West, Inc. v. Superior Court. The California Supreme Court threw out Borello's complexity and replaced it with something stark: the ABC test. Under this new standard, you're presumed to be an employee unless your employer can prove all three conditions:

A) You're free from the company's control in performing your work, both in the contract and in actual practice.

B) Your work falls outside the hiring company's usual business—like a plumber fixing a bakery's sink, not a baker making bread for a bakery.

C) You're customarily engaged in an independently established trade, meaning you've got your own business going beyond this one gig.

Miss even one of these prongs, and you're an employee. Period.

The ABC test's simplicity was its power: a rideshare company whose entire business is providing rides couldn't possibly satisfy prong B. Driving IS their usual business.

The test's simplicity was its power. A rideshare company whose entire business is providing rides couldn't possibly satisfy prong B—driving is their usual business. Food delivery platforms faced the same problem. Suddenly, millions of gig workers in California looked a lot more like employees than contractors.

California's legislature moved fast. In 2019, they passed Assembly Bill 5, codifying the ABC test into law and extending it beyond wage disputes to cover unemployment insurance, workers' compensation, and other protections. Governor Gavin Newsom signed it with fanfare, declaring victory for workers' rights.

But AB5 came loaded with carve-outs. Lawyers, doctors, real estate agents, hairstylists, graphic designers—over 100 occupations got exemptions allowing them to stay classified as contractors under the older, more flexible Borello test. The bill's authors argued these professions genuinely operated independent businesses. Critics saw something else: political horse-trading that left gig workers exposed while protecting groups with better lobbying.

The gig companies refused to comply. Instead of reclassifying drivers, Uber and Lyft spent more than $200 million on a ballot initiative to override AB5 before it could bite. They drafted Proposition 22, which would exempt app-based transportation and delivery workers from employee classification while offering a thin benefits package.

Proposition 22's campaign became a masterclass in modern political spending. The gig companies—Uber, Lyft, DoorDash, Instacart, and Postmates—poured unprecedented money into advertising that painted employee status as a threat to flexibility. Drivers would lose the freedom to set their own hours, the ads warned. They'd be stuck with rigid shifts and couldn't multi-app anymore. The companies commissioned polls, hired consultants, and blanketed California with messaging.

Labor groups fought back but couldn't match the spending. Rideshare Drivers United, a grassroots organization of gig workers, organized rallies and filed wage claims, but their budget measured in thousands, not millions.

In November 2020, Proposition 22 passed with 58 percent of the vote. App-based drivers would remain independent contractors, but with new protections: 120 percent of minimum wage for "engaged time" (not waiting time), a healthcare stipend for drivers who worked enough hours, vehicle insurance, and protection against discrimination and harassment.

The companies celebrated. Labor advocates called it a defeat for worker rights bought with corporate cash. Then researchers started looking at what Prop 22 actually delivered.

"Prop 22 promised to pay gig workers 120 percent of minimum wage, but that is based on 'active' time and does not include time they spend waiting for a ride or delivery."

— Nicole Moore, President of Rideshare Drivers United

UC Berkeley's Labor Center crunched the numbers in 2024 and found something disturbing. Because Prop 22's wage guarantee only covered "engaged time"—when a driver had a passenger or delivery—it ignored all the hours spent waiting for the next ping. When researchers calculated pay over drivers' entire shifts and subtracted expenses like gas, maintenance, and insurance, the average dropped to $5.64 per hour for rideshare drivers and $13.62 for delivery workers. Far below minimum wage.

The healthcare stipend proved equally hollow. Only 15 percent of eligible workers actually obtained it, likely because the qualification requirements—working at least 15 hours per week averaged over a quarter—excluded part-time drivers and those working for multiple platforms.

"Prop 22 promised to pay gig workers 120 percent of minimum wage," said Nicole Moore, president of Rideshare Drivers United, "but that is based on 'active' time and does not include time they spend waiting for a ride or delivery." For drivers hustling to make rent, those waiting hours add up.

Workers also noticed something else missing: accountability. Before Prop 22, misclassified workers could file complaints with California's Labor Commissioner. After it passed, no state agency had jurisdiction over gig worker complaints. The companies had effectively created a regulatory vacuum.

Legal challenges came quickly. In 2021, the Service Employees International Union and several drivers sued, arguing that Prop 22 violated California's constitution by limiting the legislature's power to regulate workers' compensation and by restricting workers' right to organize.

In August 2021, Alameda Superior Court Judge Frank Roesch agreed. His ruling declared Prop 22 unconstitutional and struck it down entirely. The decision represented a major victory for labor advocates who had fought the measure since its inception.

But the story didn't end there. The gig companies immediately appealed, and the California Court of Appeal reversed the lower court's decision. In 2024, the California Supreme Court upheld Proposition 22, finding it didn't violate the state constitution. The judicial wrangling illustrated something important: even industry-backed ballot measures that limit worker protections can survive constitutional scrutiny if voters approved them.

The court's decision left workers with few options. They couldn't appeal to state regulators. The ballot measure included a poison pill requiring a seven-eighths supermajority in the legislature to amend it—an impossible threshold. Their only path forward was litigation.

Enter California's Justice Department, along with the city attorneys of San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Diego. In 2020, they filed a massive wage-theft lawsuit against Uber and Lyft, seeking back pay and damages for drivers who worked from 2016 to 2020—the period between Dynamex and Prop 22.

The case's scope is staggering. Rideshare Drivers United estimates the 5,000 drivers who filed individual wage claims are owed at least $1.3 billion. If all 250,000 drivers from that period joined the lawsuit, the liability could reach tens of billions.

The parties are currently in mediation. Settlement negotiations reportedly include not just back pay but new benefits like minimum mileage rates and just-cause protections for deactivations—protections that go beyond Prop 22. If no deal emerges, the case goes to trial in 2026.

"It's a long legal battle that could weigh heavily on a resource-strained government agency versus a well-resourced Uber team."

— Veena Dubal, Law professor at UC Irvine

Veena Dubal, a law professor at UC Irvine who studies gig work, offered a sobering assessment: "It's a long legal battle that could weigh heavily on a resource-strained government agency versus a well-resourced Uber team." The companies have already demonstrated their willingness to spend whatever it takes.

California isn't the only battlefield. In 2024, Uber settled a class-action lawsuit covering 385,000 drivers in California and Massachusetts for $84 million, with an additional $16 million if the company went public. The drivers got checks ranging from a few hundred to a few thousand dollars each—and in return, they agreed not to pursue claims for employee status.

The settlement included minor policy concessions: drivers would get more transparency about Uber's rating system and could appeal deactivations based on low ratings. But they remained independent contractors without minimum wage guarantees, overtime, or benefits.

Less than two weeks after that settlement, lawyers filed similar class-action lawsuits in Florida and Illinois. The pattern reveals a strategy: settle where you must, preserve the classification everywhere, and keep fighting state by state.

For gig companies, these settlements serve a dual purpose. They resolve immediate legal threats while maintaining the contractor model that keeps labor costs down. $84 million sounds like a lot until you compare it to the 30 percent increase in ongoing labor costs that reclassification would trigger.

California's battles are just one front in a worldwide regulatory war. Different jurisdictions have taken radically different approaches to the gig worker question, each reflecting their own labor traditions and political realities.

Europe's Regulatory Push: The European Union passed a directive in 2024 establishing a presumption of employment for platform workers, shifting the burden of proof to companies. Member states must transpose it into national law by 2026. The UK Supreme Court ruled in 2021 that Uber drivers were workers entitled to minimum wage and holiday pay, forcing the company to reclassify drivers across Britain.

Spain went further, passing a "Rider Law" in 2021 that presumes all delivery platform workers are employees. The law came after years of organizing by riders who formed unions and staged strikes over dangerous working conditions and low pay.

Australia's Middle Path: Australia created a third category—"employee-like workers"—who get some protections without full employee status. The system acknowledges that gig work doesn't fit neatly into traditional employment boxes but still deserves basic safeguards.

Asian Flexibility: In contrast, much of Asia has maintained lighter regulatory touch. Singapore, Japan, and South Korea allow platform companies wide latitude to classify workers as contractors, though some protections like insurance requirements exist. The approach reflects cultural preferences for flexible labor markets and concern about hampering innovation.

These international variations create a patchwork that global platforms must navigate. Uber's employment practices differ dramatically between London and Singapore because the legal frameworks demand it. The question is whether regulations will converge or remain fragmented.

All this legal wrangling happens because misclassification carries serious consequences. Up to 15 percent of employers are believed to wrongly classify at least one worker as an independent contractor, and the penalties can be severe.

The IRS wants back taxes—both the employer's share of Social Security and Medicare that wasn't paid and the employee's share that wasn't withheld. State unemployment and workers' compensation agencies pile on their own claims. Workers can sue for unpaid minimum wage, overtime, meal breaks, and expense reimbursements going back several years.

For individual companies, the exposure adds up fast. When Uber calculated the cost of reclassifying drivers as employees, they estimated a 30 percent jump in labor costs including taxes, insurance premiums, workers' compensation, and benefits. Applied to hundreds of thousands of drivers across multiple states, that reaches billions annually.

That's why companies fight so hard. It's not just about one lawsuit or one ballot measure. It's about preserving a business model that depends on avoiding those costs.

The classification battle isn't really about legal tests or regulatory definitions. It's about a business model that depends on keeping labor costs down by avoiding employer responsibilities.

Despite the power imbalance, gig workers have organized. Rideshare Drivers United organized 5,000 drivers to file individual wage claims with California's Labor Commissioner in 2020, an unprecedented mobilization that led directly to the state's wage-theft lawsuit. They've held rallies at city halls in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Diego, demanding accountability.

In New York, the Independent Drivers Guild negotiated with Uber for rights including a minimum trip payment and the ability to appeal deactivations. Though not a formal union—contractors can't legally unionize under federal law—the guild demonstrated that collective action could extract concessions even without employee status.

Delivery workers have organized too. Los Deliveristas Unidos in New York successfully pushed for first-of-its-kind protections including bathrooms access, minimum pay, and tip transparency. App-based delivery workers in several cities have coordinated strikes over algorithm changes that cut their pay.

"We're asking the state to stand strong, the cities to have a backbone, and not let these companies off the hook," said Nicole Moore of Rideshare Drivers United. Her organization represents a broader movement challenging the notion that gig work must mean precarious work.

Understanding the legal battles requires understanding how courts and agencies actually determine employment status. Three main tests dominate:

The Common Law Test: Used by the IRS for employment tax purposes, this examines behavioral control (does the company direct how work is done?), financial control (who provides tools and bears business risk?), and the overall relationship between parties. It's flexible but unpredictable, with different factors weighted differently depending on the industry and circumstances.

The ABC Test: Adopted by California and several other states, this creates a presumption of employment that companies must overcome by proving all three conditions. Its simplicity and worker-friendly burden of proof make it powerful for enforcement but controversial with businesses that argue it's too rigid.

The Economic Reality Test: Used by the Department of Labor under some administrations, this looks at whether workers are economically dependent on a company or truly in business for themselves. Factors include the permanency of the relationship, degree of skill required, worker's investment in equipment, control over profit and loss, and whether the work is integral to the employer's business.

Different tests produce different outcomes. A rideshare driver might pass the common law test but fail the ABC test because driving is integral to a rideshare company's business. A freelance writer might satisfy the ABC test because writing isn't the core business of the tech company that hired her, but fail the economic reality test because she depends on that one client for most of her income.

This confusion creates opportunity for misclassification, whether intentional or accidental. Many companies genuinely believe their contractors are properly classified, only to discover during an audit that regulators disagree. Others exploit the ambiguity deliberately, knowing enforcement is spotty.

The classification question isn't academic. It determines whether millions of workers receive basic protections that employees take for granted:

Wages and Hours: Employees get minimum wage and overtime pay. Contractors get whatever they can negotiate, which in gig work often means whatever the algorithm decides. Employees receive guaranteed meal and rest breaks. Contractors don't.

Benefits: Employees typically receive health insurance, retirement contributions, paid time off, and disability coverage. Contractors get none of this unless they purchase it themselves at retail prices.

Protections: Employees enjoy anti-discrimination protections, can't be fired without cause in many jurisdictions, and have whistleblower protections. Contractors can be "deactivated" with no explanation or recourse. Employees have workers' compensation if injured on the job. Contractors bear their own medical costs.

Taxes: Employers withhold income and payroll taxes for employees and pay half of Social Security and Medicare. Contractors pay all of it themselves—the "self-employment tax"—and must make quarterly estimated payments to avoid penalties.

Organizing Rights: Employees can legally unionize under the National Labor Relations Act. Contractors attempting to organize collectively risk antitrust prosecution for price-fixing.

For someone driving full-time for Uber, these differences determine whether they can afford health insurance for their kids, whether an accident means bankruptcy, and whether they have any say in the algorithm changes that cut their income.

One wrinkle that traditional employment law didn't anticipate: algorithmic management. Uber doesn't have shift supervisors who tell drivers where to go. Instead, an algorithm assigns rides, adjusts pricing, monitors performance, and decides who gets deactivated—all without human intervention.

This creates classification puzzles. Uber argues drivers have freedom because no human boss directs them. Drivers respond that algorithmic control is still control—they can't negotiate rates, don't know how the algorithm evaluates them, and face deactivation if they reject too many rides. The app decides which rides they see, which routes they should take, and how much they'll earn.

Courts are still figuring out how to analyze this. The ABC test's "control" prong traditionally focused on human supervision. Does algorithmic control count? Some judges say yes, others aren't sure. The legal uncertainty gives companies room to argue their way is different, more modern, beyond old labor law categories.

This matters beyond gig work. As more companies adopt algorithmic management—tracking warehouse workers' movements, rating customer service representatives, optimizing delivery routes—the question of whether algorithm-mediated control counts for employment law will shape millions of working relationships.

The legal battles over gig worker classification won't resolve anytime soon. Too much money and too many competing interests are involved. But several trends seem clear:

More State Variation: As federal legislation remains gridlocked, states will continue experimenting with different approaches. Some will adopt the ABC test, others will carve out gig worker exceptions, still others will create new categories of "portable benefits" that follow workers across platforms. This patchwork creates compliance headaches for national platforms but allows policy innovation.

Continued Litigation: The California wage-theft case is just one of many lawsuits working through courts nationwide. Even if companies prevail in some jurisdictions, they'll face ongoing legal exposure in others. Settlements will continue, buying peace without admitting the underlying classification was wrong.

International Pressure: As Europe, the UK, and other jurisdictions strengthen gig worker protections, platforms operating globally will face pressure to standardize practices. It's hard to argue drivers need flexibility in California while accepting employee status in London. Regulatory arbitrage has limits.

Worker Power: Despite lacking formal collective bargaining rights, gig workers are organizing more effectively. Grassroots groups like Rideshare Drivers United and Los Deliveristas Unidos show that even contractors can mobilize for better conditions. Their success will inspire others.

Technological Adaptation: Some platforms are experimenting with alternative models. A few allow workers to set their own rates or see full trip information before accepting. Others are adding benefit options contractors can purchase at group rates. These changes acknowledge that the pure contractor model faces growing political resistance.

Beneath all the legal technicalities lies a fundamental question about the future of work: As algorithms replace bosses and gig platforms replace employers, should workers' rights evolve too?

Traditional employment law assumed companies would act like employers—hiring workers, supervising them, taking responsibility for their welfare. That social contract, forged during the industrial revolution and strengthened during the New Deal, traded workers' autonomy for security and protection. You couldn't choose your hours or methods, but you got a steady paycheck and benefits.

The gig economy flips this. It promises autonomy—work when you want, be your own boss—but delivers precarity. You choose your hours, but the algorithm chooses your pay. You're an independent business, but you can't negotiate rates or see your performance metrics. You have flexibility, but no security.

Maybe the old categories don't fit anymore. Maybe we need new ones that provide baseline protections without requiring traditional employment relationships. Portable benefits that follow workers between gigs. Algorithmic transparency so workers understand how they're evaluated. Just-cause standards for deactivation. Collective bargaining rights for contractors.

Or maybe the old categories fit just fine, and we just need to enforce them. Maybe when a company controls how much you earn, when you work, what customers you serve, and whether you keep working at all, they're your employer no matter what the contract says.

The courts are still deciding. So are legislatures. So are voters. And so are millions of gig workers who, every day, navigate a system that promises them freedom while denying them security—and who are starting to demand both.

The question of who really works for Uber matters far beyond rideshare drivers. It's a test case for whether labor law can adapt to algorithmic capitalism in the 21st century.

What's certain is this: the question of who really works for Uber matters far beyond rideshare drivers. It's a test case for whether labor law can adapt to algorithmic capitalism, whether workers can organize in the platform economy, and whether economic innovation must come at workers' expense. The answer we choose will shape work for generations.

In 2004, Dynamex thought reclassifying drivers was a simple cost-saving move. Twenty years later, that decision is still echoing through courtrooms, ballot boxes, and streets full of protesting drivers. The algorithm might decide who gets the next ride, but workers, courts, and voters will decide who counts as an employee. That battle has decades left to run.

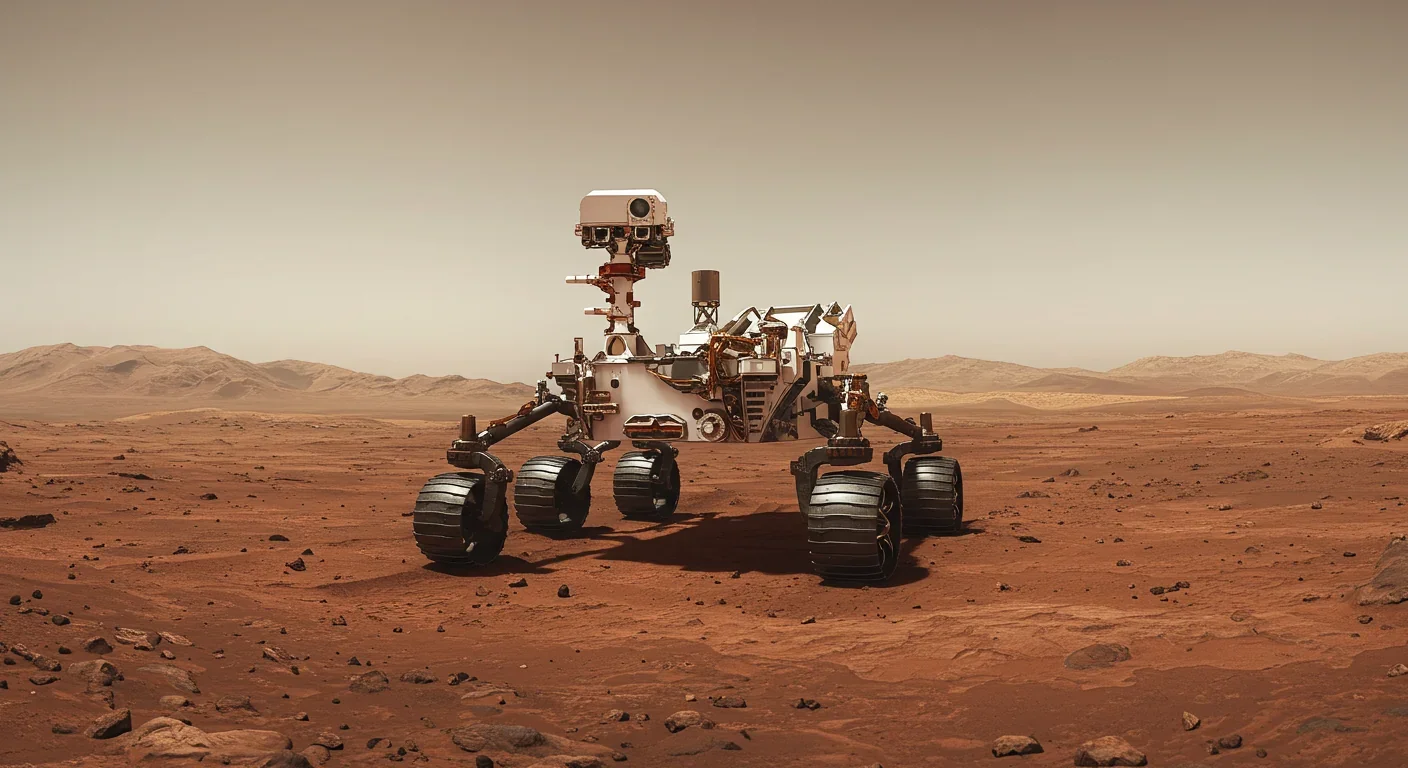

Curiosity rover detects mysterious methane spikes on Mars that vanish within hours, defying atmospheric models. Scientists debate whether the source is hidden microbial life or geological processes, while new research reveals UV-activated dust rapidly destroys the gas.

CMA is a selective cellular cleanup system that targets damaged proteins for degradation. As we age, CMA declines—leading to toxic protein accumulation and neurodegeneration. Scientists are developing therapies to restore CMA function and potentially prevent brain diseases.

Intercropping boosts farm yields by 20-50% by growing multiple crops together, using complementary resource use, nitrogen fixation, and pest suppression to build resilience against climate shocks while reducing costs.

The Baader-Meinhof phenomenon explains why newly learned information suddenly seems everywhere. This frequency illusion results from selective attention and confirmation bias—adaptive evolutionary mechanisms now amplified by social media algorithms.

Plants and soil microbes form powerful partnerships that can clean contaminated soil at a fraction of traditional costs. These phytoremediation networks use biological processes to extract, degrade, or stabilize toxic pollutants, offering a sustainable alternative to excavation for brownfields and agricultural land.

Renters pay mortgage-equivalent amounts but build zero wealth, creating a 40x wealth gap with homeowners. Institutional investors have transformed housing into a wealth extraction mechanism where working families transfer $720,000+ over 30 years while property owners accumulate equity and generational wealth.

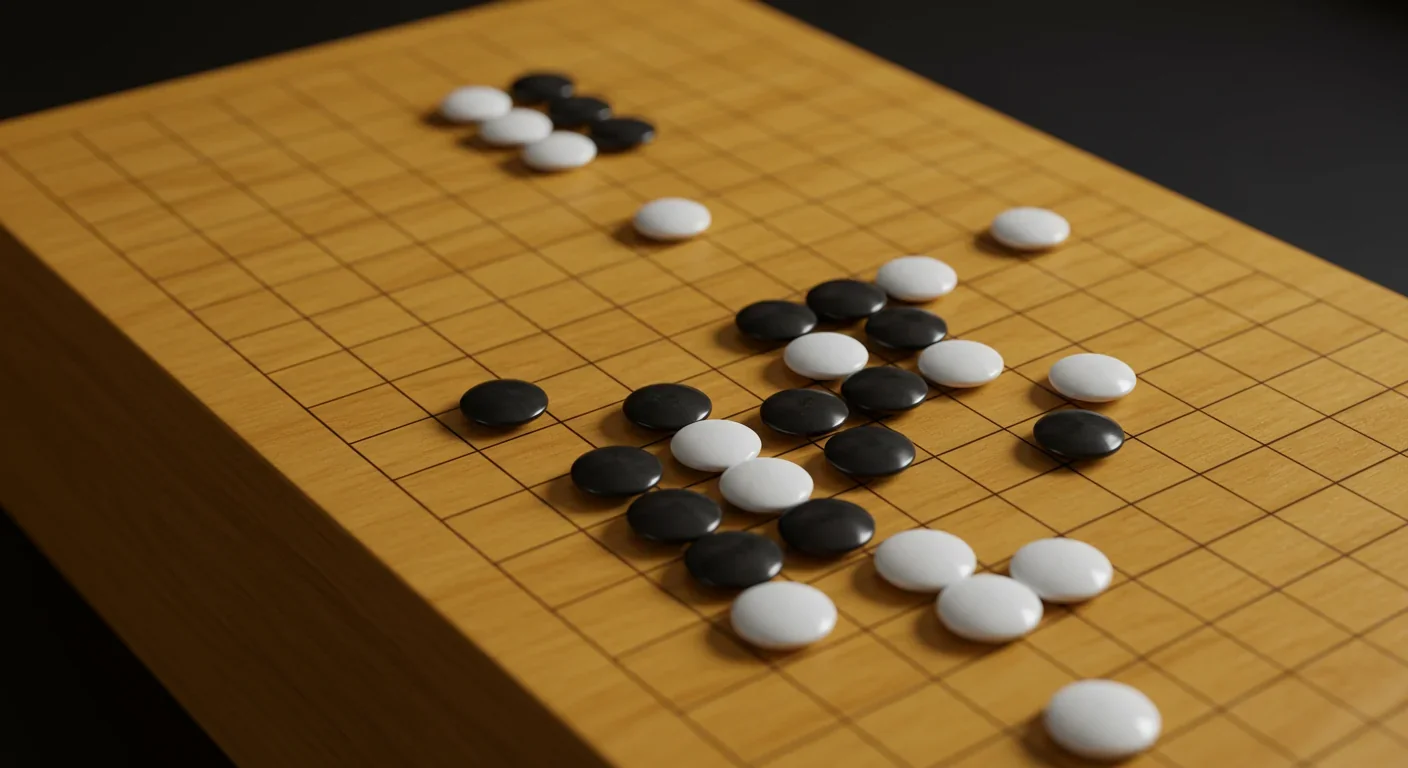

AlphaGo revolutionized AI by defeating world champion Lee Sedol through reinforcement learning and neural networks. Its successor, AlphaGo Zero, learned purely through self-play, discovering strategies superior to millennia of human knowledge—opening new frontiers in AI applications across healthcare, robotics, and optimization.