Why Everything You Learn Suddenly Seems Everywhere

TL;DR: Religious communities worldwide engage in painful rituals because suffering functions as an impossible-to-fake signal of commitment. These costly displays filter out free-riders, create physiological synchrony between participants, and forge intense social bonds through shared sacrifice.

Picture a man walking barefoot across a bed of glowing coals, his heart hammering at 200 beats per minute while his face remains eerily calm. In Mauritius, devotees pierce their cheeks with metal skewers during Thaipusam, then donate twice as much to charity as those who merely watched. Across the world, Shia Muslims flagellate themselves in public rituals, Christians undertake extreme fasts, and countless communities demand financial sacrifices that stretch household budgets. These practices look irrational, even dangerous. So why do religions worldwide double down on rituals that hurt, cost, or exhaust their followers?

The answer reveals something profound about human psychology: suffering isn't a bug in religious systems, it's a feature. Behind these seemingly masochistic traditions lies costly signaling theory, a framework borrowed from evolutionary biology that explains how pain becomes proof, how sacrifice builds trust, and how the very irrationality of ritual makes it impossible to fake. When you've watched your neighbor stab hooks through their flesh or fasted until their body screamed for food, you've witnessed something that lazy believers simply can't replicate. That's the whole point.

Religious practices often appear maladaptive from an evolutionary standpoint. Genital modification, food and water deprivation, snake handling—none of these behaviors seem to enhance survival or reproduction. If natural selection favors efficiency, why hasn't it weeded out these wasteful displays?

The paradox dissolves once you understand the problem religious communities evolved to solve: free riders. In any cooperative group, there's an incentive to enjoy the benefits of membership without paying the costs. The free rider problem becomes especially acute in large religious communities where monitoring individual commitment is difficult and the benefit from any single person's contribution feels small. If everyone can fake devotion, how do you know who's genuinely committed?

Costly rituals solve this by making commitment impossible to counterfeit. Unlike verbal promises or symbolic gestures, walking on fire or enduring hours of ritual pain requires genuine sacrifice.

Costly rituals solve this by making commitment impossible to counterfeit. Unlike verbal promises or symbolic gestures, walking on fire or enduring hours of ritual pain requires genuine sacrifice. These displays function as what biologists call "handicap signals"—like a peacock's unwieldy tail, their very costliness proves authenticity. A half-hearted believer won't voluntarily skewer their tongue, making extreme ritual a powerful filter.

Research supports this theory quantitatively. Members of religious kibbutzes demonstrated significantly higher cooperation in common-pool resource games compared to their secular counterparts. The difference wasn't in belief alone, it was in the costliness of their daily religious practices. When participation in a ritual has a high price, people who pay it reveal genuine commitment—and that knowledge transforms how communities function.

So costly rituals filter out the uncommitted. But why does watching someone suffer create bonds between observers? The answer lies in how our brains process social and physical pain.

Neuroscience reveals that social exclusion activates the same brain regions—the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex and anterior insula—that fire when we experience physical injury. Our nervous systems don't distinguish between being burned and being rejected. This neural overlap means that witnessing someone endure pain for the group triggers empathic responses that go beyond intellectual acknowledgment. When 40 spectators watched firewalkers in San Pedro Manrique, researchers measured their heart rates and found something remarkable: observers' hearts synchronized with the walkers, and the degree of synchrony correlated directly with how socially close they felt to the participant.

"When a participant crosses the fire, their heart rate approaches 200 beats per minute, yet they claim to feel calm."

— Firewalking participant, San Pedro Manrique study

This physiological mirroring creates what sociologists call "collective effervescence"—the heightened emotional state that arises when people share intense experiences. It's why military boot camps put recruits through grueling ordeals, why fraternities use painful hazing, and why religious pilgrimages involve hardship by design. The pain isn't incidental, it's the mechanism through which individual nervous systems align into collective consciousness.

But there's another layer. When rituals are performed publicly, the entire community becomes witness to the sacrifice. This creates accountability. If you claim membership in a group but refuse its defining ordeal, everyone knows. Religious rituals are often complex, involving precise choreography that makes mistakes easy to spot. This visibility eliminates plausible deniability—you can't fake having walked the coals when the soles of your feet are examined afterwards.

The Mauritian Thaipusam study illustrates the behavioral consequences. Devotees who experienced the most pain during the ritual—measured by the severity of their body piercings and physical exertion—gave significantly more money to charity afterward than those who participated in less costly prayer ceremonies. The more it hurt, the more they gave. This wasn't abstract altruism, it was prosocial behavior directly proportional to ritual cost.

Here's where the story gets uncomfortable. The same mechanisms that forge tight-knit communities can also fuel intergroup conflict. Research on religion and aggression reveals a troubling pattern: religious devotion simultaneously increases prosocial behavior toward fellow believers while heightening prejudice and aggression toward outsiders.

Studies by Teehan, Johnson, and Bushman document that priming religious concepts increases cooperation between group members but also supports aggressive attitudes toward those outside the faith. Costly rituals don't just say "I'm committed to my community"—they implicitly declare "I'm willing to suffer for us versus them." The same public display of endurance that builds internal trust can become a rallying point for external hostility.

Iannaccone's research on cults and communes showed that groups with higher ritual costs exhibited less free-riding but also stronger boundaries between members and non-members. When sacrifice defines group identity, those who haven't sacrificed become outsiders by definition. This dynamic helps explain why religious extremism often emerges from communities that practice especially demanding rituals—the very features that make them cohesive internally also make them insular and potentially hostile externally.

When sacrifice defines group identity, those who haven't sacrificed become outsiders by definition. This is how cohesive communities can simultaneously become insular and hostile to outsiders.

The evolutionary logic is grimly consistent. Religion may have evolved as much for coordinating warfare as for fostering cooperation. Costly rituals prepare believers not just to trust each other but to fight alongside each other. When your comrade has proven they can endure extraordinary pain for the faith, you trust they won't abandon you in battle. Conversely, anyone who hasn't proven themselves through ritual becomes suspect—a potential threat rather than an ally.

Understanding costly signaling theory isn't just academic—it provides practical frameworks for navigating contemporary challenges. Take radicalization. Terrorist organizations deliberately impose costly demands on recruits: isolation from family, surrender of personal resources, participation in dangerous activities. These requirements aren't arbitrary, they're engineered to filter out infiltrators and build unshakeable commitment through the same psychological mechanisms as religious ritual.

Counterterrorism experts increasingly recognize that disrupting extremist groups requires more than ideology. It means providing alternative pathways for demonstrating commitment and belonging. Programs that channel the human need for costly signaling into prosocial rituals—demanding athletic challenges, intensive community service, difficult educational achievements—can satisfy the same psychological drives without violence.

Conversely, secular communities struggling with cohesion might learn from religious models. Rituals create shared experiences that connect people and strengthen their sense of community. When traditional religious participation declines, societies lose more than belief systems, they lose the bonding mechanisms those systems provided. Some emerging communities are deliberately designing new rituals: endurance events, intensive retreats, communal projects that demand real sacrifice. These secular equivalents aim to capture the social benefits of costly signaling without religious content.

China's experience with individualized religious practices offers another angle. In a mobile society where 150 million rural migrants have relocated to cities, collective rituals became impractical. Yet 76% of urban Chinese still practice ancestral worship—an individualized ritual that carries personal cost. Research shows this adaptation preserves the psychological benefits of traditional practices while allowing flexibility. Participants report lower anxiety and higher social inclusion scores, suggesting costly signals can function even when performed privately, provided they involve genuine sacrifice visible to the community.

Not all rituals generate equal bonding. Three factors determine whether a practice will strengthen community commitment:

Intensity of cost: The ritual must genuinely hurt, exhaust, or deprive. Lighting a candle doesn't bond people the way fasting for days does. Neuroscientific studies show a dose-response relationship—more pain correlates with stronger physiological synchrony and subsequent cooperation. This explains the "ritual ratchet" observed across religions, where communities gradually intensify their practices to maintain their signaling value. Once everyone fasts for 24 hours, someone inevitably starts fasting for 48 to demonstrate superior commitment.

Public visibility: Private suffering doesn't signal. Rituals performed collectively create mutual vulnerability and shared witness. When your community watches you endure pain, you can't later claim you didn't really suffer. This witnessability makes the signal credible in ways individual practice cannot. It also explains why religious communities often resist privatization of ritual—moving practice from public squares to private homes undermines its social function.

Difficulty of faking: Complex rituals with observable outcomes work better than simple ones. Anyone can claim they prayed sincerely, but walking across hot coals without flinching requires visible proof. The body reveals what the mouth might hide. This is why religious rituals are often elaborate, involving precise steps, specific timing, and physical markers. The complexity serves as quality control.

"The more painful they felt, the more money they gave to charity."

— Thaipusam study results, Mauritius

Interestingly, perceived cost matters as much as objective cost. Placebo studies demonstrate that belief shapes pain experience—when people expect rituals to be difficult, their nervous systems respond accordingly. This suggests communities can modulate bonding effects not just by changing rituals but by shaping how those rituals are framed and experienced. A ritual accompanied by narratives emphasizing its extreme difficulty may generate stronger effects than an objectively harder ritual presented as routine.

As traditional religion declines in many societies, what happens to the human need for costly signaling? We're already seeing substitutes emerge.

Consider CrossFit culture, marathon running communities, or intense bootcamp fitness programs. These secular rituals demand physical suffering, public performance, and visible proof of commitment. Participants develop the kind of tight social bonds traditionally associated with religious communities. They're not praying together, they're suffering together—and their brains can't tell the difference.

Social media introduces a new twist: virtualized costly signaling. When someone posts a 5AM gym selfie or documents their 30-day challenge, they're broadcasting signals of discipline and commitment to their digital community. These displays lack the physical co-presence of traditional ritual, but they retain key features—visible sacrifice, public witness, difficulty of faking (timestamped photos, tracking apps). Whether virtual signals generate the same depth of bonding remains an open question.

Some researchers worry we're losing something irreplaceable. Digital rituals can be curated, filtered, abandoned without consequence. You can fake a fitness journey with strategic photo angles in ways you can't fake walking on coals. If costly signaling works because it filters out low-commitment members, easy-to-fake virtual versions might fail to generate real cohesion.

Others argue the underlying mechanisms will adapt. Throughout history, what counts as "costly" has shifted based on context. In agricultural societies, sacrificing livestock represented enormous economic cost. In modern economies, time sacrifice—dedicating weekends to community service, committing to regular meetings—may serve similar functions. The question isn't whether we need costly rituals, it's what forms they'll take as our social landscape evolves.

Religious rituals reveal a paradox at the heart of human community: we bond most deeply through shared suffering. Our brains are wired to trust people who've proven commitment through costly signals, and to feel connected to those who've suffered alongside us. This mechanism produces both the best and worst of human behavior—selfless cooperation within groups, tribalism and violence between them.

By making belief costly, religions make it credible. By making ritual painful, they make it meaningful. This isn't a bug in the human operating system—it's how we're built.

From an outside perspective, watching someone walk on fire or pierce their flesh still looks irrational. But from the inside, these rituals solve a fundamental problem: how to build trust in a world where everyone has incentive to fake commitment. By making belief costly, religions make it credible. By making ritual painful, they make it meaningful.

We can't escape this logic just because we understand it. Even knowing that our emotional responses to ritual are products of evolutionary psychology doesn't make those responses less real. When we watch someone sacrifice for their community, we feel respect and connection—not because we're fooled, but because we're human. The costlier the signal, the more our instincts trust it.

The challenge ahead isn't eliminating costly signaling—that's probably impossible—but channeling it wisely. Can we design rituals that build cohesion without fueling conflict? Can we satisfy our need for meaningful sacrifice through prosocial rather than destructive means? Can we maintain the bonding benefits of costly ritual while reducing its capacity for extremism?

Religious communities have been running this experiment for thousands of years, refining practices that speak to something deep in our psychology. Whatever your beliefs about the supernatural, the social science is clear: pain, properly structured and communally shared, creates bonds that comfort never could. That's not a bug in the human operating system. For better or worse, it's how we're built.

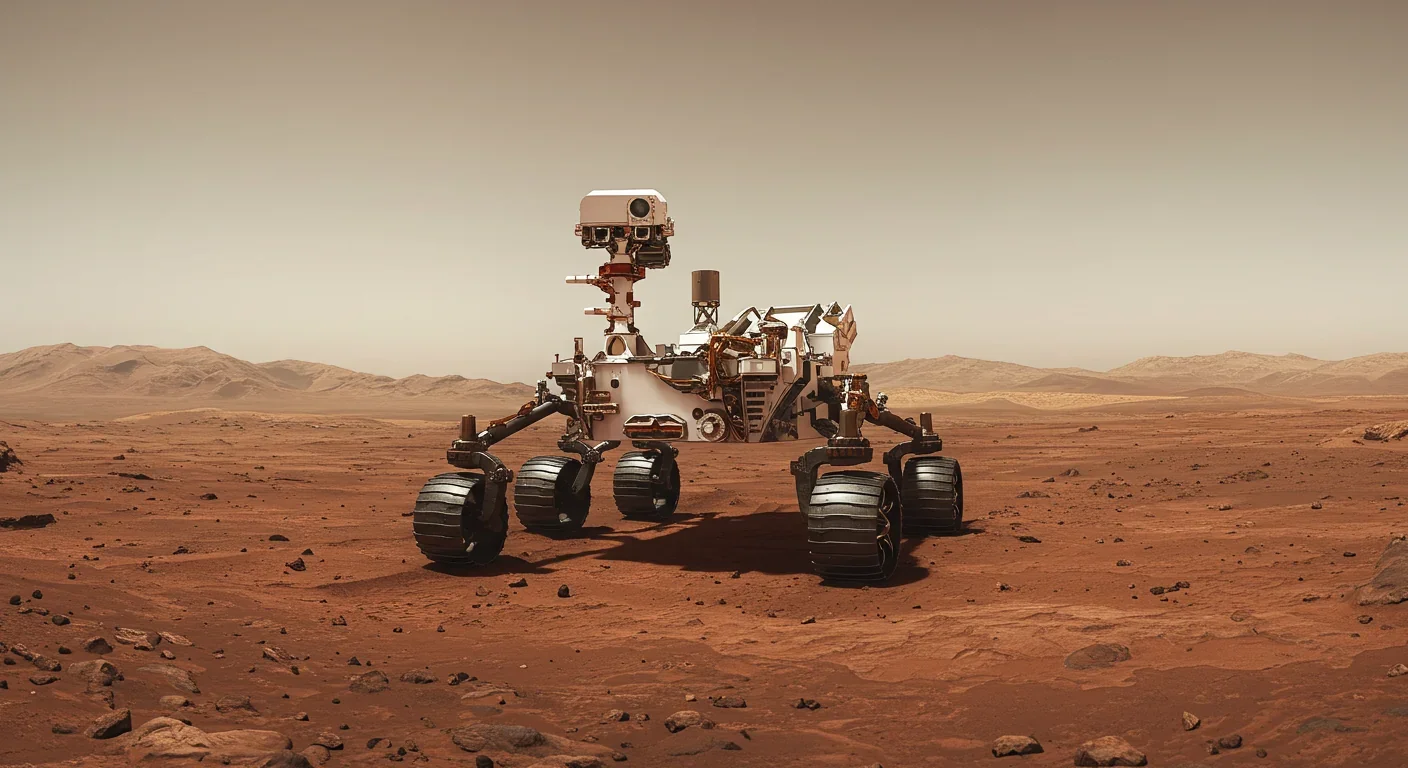

Curiosity rover detects mysterious methane spikes on Mars that vanish within hours, defying atmospheric models. Scientists debate whether the source is hidden microbial life or geological processes, while new research reveals UV-activated dust rapidly destroys the gas.

CMA is a selective cellular cleanup system that targets damaged proteins for degradation. As we age, CMA declines—leading to toxic protein accumulation and neurodegeneration. Scientists are developing therapies to restore CMA function and potentially prevent brain diseases.

Intercropping boosts farm yields by 20-50% by growing multiple crops together, using complementary resource use, nitrogen fixation, and pest suppression to build resilience against climate shocks while reducing costs.

The Baader-Meinhof phenomenon explains why newly learned information suddenly seems everywhere. This frequency illusion results from selective attention and confirmation bias—adaptive evolutionary mechanisms now amplified by social media algorithms.

Plants and soil microbes form powerful partnerships that can clean contaminated soil at a fraction of traditional costs. These phytoremediation networks use biological processes to extract, degrade, or stabilize toxic pollutants, offering a sustainable alternative to excavation for brownfields and agricultural land.

Renters pay mortgage-equivalent amounts but build zero wealth, creating a 40x wealth gap with homeowners. Institutional investors have transformed housing into a wealth extraction mechanism where working families transfer $720,000+ over 30 years while property owners accumulate equity and generational wealth.

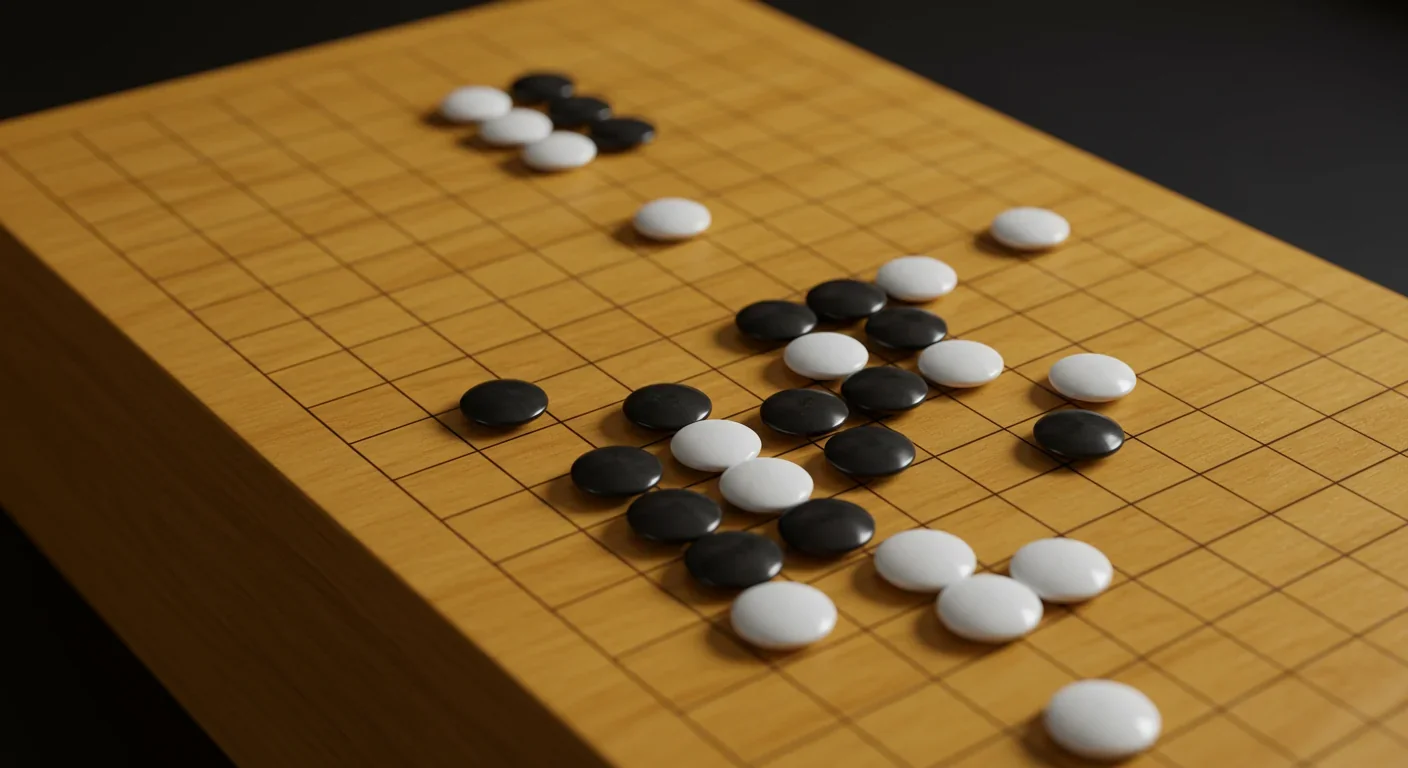

AlphaGo revolutionized AI by defeating world champion Lee Sedol through reinforcement learning and neural networks. Its successor, AlphaGo Zero, learned purely through self-play, discovering strategies superior to millennia of human knowledge—opening new frontiers in AI applications across healthcare, robotics, and optimization.