The Hidden Memory Trap: Why Your Ideas Aren't Original

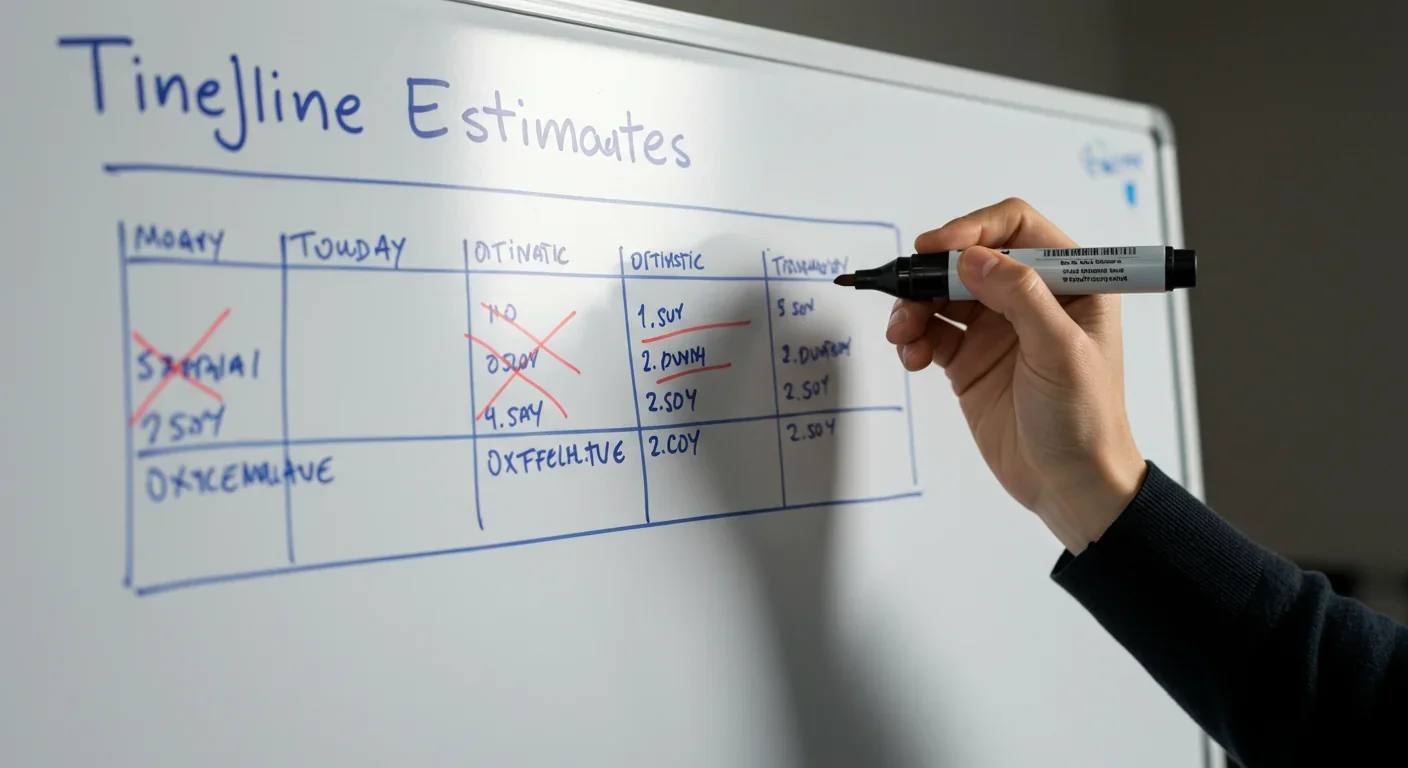

TL;DR: The planning fallacy—our systematic tendency to underestimate task time and costs—affects everyone from NASA engineers to daily commuters. Discovered by Kahneman and Tversky, this bias costs billions in project overruns and wrecks personal schedules. Research reveals proven countermeasures: take the outside view using historical data, apply percentage buffers, conduct premortems, and build systems that compensate for our optimistic brains.

You wake up, check your to-do list, and confidently tell yourself you'll finish by lunch. By dinner, you're still working. Sound familiar? You're not alone, and you're not lazy. You've fallen victim to one of the most pervasive cognitive biases in human psychology: the planning fallacy. This systematic tendency to underestimate how long tasks will take and how much they'll cost affects everyone from students writing papers to governments building airports.

The planning fallacy was first identified by psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in 1979, and it explains why your "quick five-minute task" consistently balloons into an hour. More troubling, it reveals why billion-dollar infrastructure projects routinely double or triple their budgets. Understanding this bias means understanding why humans are fundamentally terrible at predicting their own futures—and what we can do about it.

The numbers tell a stark story. The Sydney Opera House was supposed to cost $7 million and open in 1963. It actually cost $102 million and opened in 1973—a stunning 1,357% cost overrun. The Denver International Airport opened 16 months late and nearly $3 billion over budget. The Edinburgh Tram Line 2 was forecasted at £320 million but came in at £776 million—a 93% overrun.

These aren't isolated incidents. According to research published in the Project Management Journal, the planning fallacy can result in cost overruns of up to 50% or more in large infrastructure projects. A comprehensive study by Oxford researcher Bent Flyvbjerg found that optimism bias is one of the biggest single causes of risk for megaproject overspend.

The planning fallacy can result in cost overruns of up to 50% or more in large infrastructure projects, affecting billions in public and private spending worldwide.

But the planning fallacy isn't just bankrupting governments. It's wrecking your personal schedule too. In a 1994 study cited on Wikipedia, psychology students estimated they'd finish their senior theses in an average of 33.9 days. The actual average? 55.5 days—a 64% underestimate. Another study found that Canadian taxpayers mailed their tax forms a full week later than they predicted, despite knowing their past performance.

The pattern is unmistakable: we consistently, predictably, and stubbornly underestimate how long things will take.

So what's happening in your brain when you make these wildly inaccurate predictions? The answer lies in what Kahneman called the "inside view"—our tendency to focus intensely on the specific task ahead while ignoring broader statistical realities.

When you think about writing a report, your brain constructs a best-case scenario: you'll sit down, words will flow, nothing will interrupt you. This mental simulation feels vivid and real. What you don't consider are all the inevitable complications—the email that requires an urgent response, the research that takes longer than expected, the paragraph you'll rewrite five times.

Kahneman experienced this firsthand when he and colleagues were writing a textbook on judgment. A year into the project, each team member estimated they'd need 1.5 to 2.5 more years to finish. But when one colleague checked data from similar projects, he found they typically took 7 to 10 years—and 40% never finished at all. The group's actual completion time? Eight years. Even Kahneman, a world expert on cognitive bias, couldn't escape his own optimism.

"The planning fallacy is an irrational perseverance, a delusional forecast that persists even when evidence suggests otherwise."

— Daniel Kahneman

This happens because of several interconnected psychological mechanisms. First, there's what Kahneman calls WYSIATI—"What You See Is All There Is." Your brain doesn't naturally account for unknown unknowns or consider information that isn't immediately present. When planning, you focus on what you can see and control, not on the countless ways reality might deviate from your plan.

Second, there's memory bias. When you recall past similar tasks, your memory systematically underestimates how long they actually took. You remember starting and finishing, but not all the delays in between. This means even learning from experience doesn't protect you—your brain is learning from corrupted data.

Third, motivation warps perception. Research shows that when people make predictions anonymously, they don't show the same optimistic bias. But when others are watching, we tend to lowball estimates to appear competent and confident. Project managers know that proposing realistic timelines might kill a project before it starts, so they unconsciously (or deliberately) underestimate to secure approval.

You might think experience would inoculate against the planning fallacy. It doesn't. The Brillity Digital blog describes an experiment where two groups of experts estimated project timelines without communicating. Both groups' best-case and worst-case estimates came within three days of each other. Both were wrong by 40%.

Even NASA, with its rigorous planning processes and brilliant engineers, systematically underestimated software project effort by 1.4 to 4.3 times over a 16-year period. When software professionals rate themselves at 90% confidence that their effort estimates will hold, they're right only 60–70% of the time, according to research on software development estimation.

Why doesn't expertise help? Because the inside view is seductive. Experts have deep knowledge of their domain, which paradoxically makes them more confident in their unique understanding of the task. They genuinely believe their project is different, that their skills will overcome typical obstacles. This is what happened with Sony's Chromatron project in the 1960s. Despite optimistic projections, costs stubbornly remained more than double the retail price, and after producing over ten thousand units, the entire product line was scrapped.

The UK's Behavioural Insights Team commissioned a comprehensive literature review of the planning fallacy specifically because these biases kept appearing in national transport projects, despite the involvement of experienced professionals and consultants.

Sometimes the planning fallacy isn't just a cognitive error—it's a strategy. Project sponsors may deliberately underestimate timelines and costs to secure approval, a phenomenon researchers call strategic misrepresentation.

This creates a perverse dynamic: the person proposing a project knows that realistic estimates will seem too expensive or time-consuming, so they present optimistic numbers. Decision-makers, also subject to optimism bias, accept these rosy scenarios. By the time reality intrudes, the project is too far along to cancel. Everyone involved had incentives to believe the optimistic forecast, even when experience suggested otherwise.

This isn't always conscious deception. Motivated reasoning creates a self-reinforcing loop: Bob from engineering wants his project funded, so he makes optimistic projections. His optimism feels justified because he's an expert. His bosses want to believe him because the project aligns with strategic goals. Everyone's biases align, creating institutional momentum behind unrealistic plans.

Strategic misrepresentation occurs when project sponsors deliberately underestimate costs and timelines to secure approval—a calculated gamble that compounds cognitive bias with institutional incentives.

The result? A 2002 study found that American kitchen remodeling projects were expected to cost an average of $18,658 but actually cost $38,769—more than double. These weren't novices; these were homeowners working with professional contractors who had built dozens of kitchens.

You might think breaking a large task into smaller sub-tasks would help. Sometimes it does. Research shows that smaller tasks are less susceptible to the planning fallacy because they're easier to mentally simulate. If you estimate that drafting an outline takes 30 minutes, writing three sections takes two hours each, and editing takes an hour, you get a total of seven hours and thirty minutes—more realistic than saying "I'll write this report today."

But decomposition has a hidden danger: it can create a false sense of precision. When you add up your component estimates, you're still using the inside view for each piece. You're not accounting for transitions between tasks, dependencies that create delays, or the integration work required to assemble the pieces. Even worse, aggregating multiple underestimates compounds the error.

One study mentioned on Wikipedia found that segmentation can reduce the planning fallacy, but it requires substantial cognitive resources—so much that it's often impractical for everyday use. You'd spend more time planning than working.

The good news: decades of research have identified strategies that genuinely improve estimation accuracy.

Take the Outside View

The single most powerful intervention is what Kahneman calls taking the outside view. Instead of thinking about your specific project's unique features, look at statistical data from similar past projects. How long did the last five reports take? What was the average cost overrun on similar construction projects?

This approach, formalized as Reference Class Forecasting, has been shown to improve forecasting accuracy by up to 30% compared to traditional methods, according to a study in Management Science. The UK Department for Transport issued guidance in 2004 requiring major infrastructure projects to use reference class forecasting precisely because traditional estimates were so unreliable.

"Reference class forecasting is so named as it predicts the outcome of a planned action based on actual outcomes in a reference class of similar actions."

— Kahneman & Tversky Framework

Here's how it works: identify a "reference class" of similar completed projects, gather data on their actual outcomes, and use the distribution of those outcomes to predict yours. If 80% of similar projects took longer than 18 months, your project probably will too—even if you think yours is special.

Percentage Buffers, Not Fixed Time

Adding "a little extra time" never works. Psychology Today recommends adding 25% as a rule of thumb, though for truly novel projects, doubling your initial estimate is more realistic. Some software developers swear by the "double it" rule: whatever you first estimate, double it.

The logic is simple: if you think something will take 10 minutes, adding 5 minutes gives you 15—still likely too short. But adding 100% gives you 20 minutes, which accounts for the inevitable interruption or complexity you didn't foresee.

Premortem Analysis

Before starting a project, imagine it's failed spectacularly. Now work backwards: what went wrong? This "premortem" technique forces you to consider obstacles you'd otherwise ignore. It's the outside view in narrative form: instead of asking "What could go wrong?" (which often yields little), you assume failure and ask "What did go wrong?"

Studies show premortems uncover risks that traditional planning misses because they bypass our optimism bias. When failure is hypothetical, we defend our plan. When failure is assumed, we become remarkably good at identifying vulnerabilities.

Reassess Early and Often

Research suggests checking progress frequently and adjusting timelines early is crucial. The planning fallacy doesn't just strike once—it can recur throughout a project as new phases begin. By monitoring actual progress against predictions, you create feedback loops that help calibrate future estimates.

In clinical trials, combining I-Frame interventions with data-driven planning significantly reduces the frequency and magnitude of timeline overruns. The key is treating early deviations seriously rather than assuming you'll "make up time later"—you almost never do.

Seek External Estimates

Ask someone uninvolved in the project how long they think it will take. They're not emotionally invested in an optimistic scenario, they don't have the same motivated reasoning, and they're less likely to focus on the inside view. Their estimate will often be uncomfortably high—and probably more accurate than yours.

The planning fallacy doesn't just affect big projects. It pervades daily life in ways that create chronic stress and damaged credibility.

You tell your partner you'll be ready in five minutes and they roll their eyes because you're never ready in five minutes. You promise a client a draft by Friday and work all weekend to deliver it Monday. You plan to leave for the airport with plenty of time and find yourself sprinting to the gate. Each failure erodes trust—others' trust in you, and your own trust in your judgment.

The psychological toll is real. When you consistently fail to meet your own expectations, it's easy to conclude you're disorganized, lazy, or incompetent. But you're not. You're human. Your brain is running software optimized for motivation and confidence, not cold accuracy. Understanding this doesn't excuse poor planning, but it does shift the problem from a character flaw to a predictable bias you can systematically counteract.

The psychological toll of chronic underestimation is real: repeated failures to meet self-imposed deadlines erode both self-trust and the trust others place in you.

The planning fallacy appears across cultures, but its intensity varies. Some research suggests cultures that emphasize collective decision-making and respect for precedent may be somewhat less vulnerable. When planning requires buy-in from multiple stakeholders who've lived through past delays, the outside view naturally enters the conversation.

In contrast, cultures that lionize individual genius, rapid innovation, and "disruption" may amplify the bias. If your organizational culture celebrates the visionary who defies conventional wisdom and delivers the impossible, you're incentivizing exactly the kind of optimistic inside-view thinking that leads to the planning fallacy.

Sustainability initiatives face particularly intense versions of this problem. Projects that navigate uncertain environmental and social landscapes, with political pressures demanding optimistic timelines to maintain support, become breeding grounds for the planning fallacy. The complexity of variables far exceeds typical construction or software projects, yet political realities often require presenting confident, ambitious timelines to secure funding.

One counterintuitive finding: implementation intentions—specific plans about when, where, and how you'll complete a task—can initially make the planning fallacy worse. By recruiting willpower and making the task feel more concrete, they make it seem more doable and lower time estimates.

But over time, implementation intentions actually reduce optimism bias. Why? Because they force you to confront specific obstacles and plan around them. "I'll work on this sometime this week" allows vague optimism. "I'll work on this Tuesday from 2–4pm in my office with my phone off" forces you to consider whether that specific window is realistic given Tuesday's meetings and your typical energy levels.

This suggests a two-phase strategy: first, use implementation intentions to force concrete planning. Second, apply the outside view to your concrete plan. The combination is more powerful than either alone.

Here's the uncomfortable truth: you can't eliminate the planning fallacy. Your brain's architecture makes optimistic forecasting nearly inevitable. But you can build systems that compensate for it.

Start with self-compassion. Give yourself a break. Everyone deals with this. Beating yourself up for being "bad at time management" misses the point—you're bad at time estimation because humans are bad at time estimation. That's not a personal failing; it's a species-wide design flaw.

Then build external scaffolding. Use past data ruthlessly. Track how long tasks actually take and refer to those numbers, not your feelings. Apply percentage buffers automatically. Seek outside opinions. Build in review points that force you to update estimates based on actual progress.

For organizations, this means changing incentives. If you punish people for realistic estimates and reward optimistic ones, you guarantee planning failures. Create cultures where updating estimates based on new information is praised, not penalized. Make reference class forecasting mandatory for major projects. Separate the people who approve projects from the people who propose them to reduce motivated reasoning.

The planning fallacy reveals something profound about human nature: we're deeply uncomfortable with uncertainty, so we replace it with false confidence. A specific deadline feels better than "somewhere between three weeks and three months." A firm budget feels better than "likely between $50,000 and $200,000."

But false confidence is expensive. It leads to missed deadlines, blown budgets, damaged relationships, and chronic stress. Real confidence comes from acknowledging uncertainty and planning accordingly.

The next time you're about to say "this will only take five minutes," pause. Check similar past tasks. Add a buffer. Consider what might go wrong. You'll feel less certain—and that discomfort is actually a sign you're thinking more clearly.

Your brain will always want to believe the optimistic story. The trick is knowing when not to trust it.

Curiosity rover detects mysterious methane spikes on Mars that vanish within hours, defying atmospheric models. Scientists debate whether the source is hidden microbial life or geological processes, while new research reveals UV-activated dust rapidly destroys the gas.

CMA is a selective cellular cleanup system that targets damaged proteins for degradation. As we age, CMA declines—leading to toxic protein accumulation and neurodegeneration. Scientists are developing therapies to restore CMA function and potentially prevent brain diseases.

Intercropping boosts farm yields by 20-50% by growing multiple crops together, using complementary resource use, nitrogen fixation, and pest suppression to build resilience against climate shocks while reducing costs.

Cryptomnesia—unconsciously reproducing ideas you've encountered before while believing them to be original—affects everyone from songwriters to academics. This article explores the neuroscience behind why our brains fail to flag recycled ideas and provides evidence-based strategies to protect your creative integrity.

Cuttlefish pass the marshmallow test by waiting up to 130 seconds for preferred food, demonstrating time perception and self-control with a radically different brain structure. This challenges assumptions about intelligence requiring vertebrate-type brains and suggests consciousness may be more widespread than previously thought.

Epistemic closure has fractured shared reality: algorithmic echo chambers and motivated reasoning trap us in separate information ecosystems where we can't agree on basic facts. This threatens democracy, public health coordination, and collective action on civilizational challenges. Solutions require platform accountability, media literacy, identity-bridging interventions, and cultural commitment to truth over tribalism.

Transformer architectures with self-attention mechanisms have completely replaced static word vectors like Word2Vec in NLP by generating contextual embeddings that adapt to word meaning based on surrounding context, enabling dramatic performance improvements across all language understanding tasks.