Why Evolution Designed Children to Need More Than Two Parents

TL;DR: Our brains evolved to resist change because staying put kept our ancestors alive. Today, that same wiring traps us in suboptimal jobs, investments, and relationships—but understanding the mechanisms can help us outsmart our defaults.

You know you should switch to that cheaper phone plan. You're aware your outdated investment strategy is costing you money. Yet somehow, you stick with what you've got. Welcome to status quo bias, the invisible force keeping billions of people locked into suboptimal choices.

This isn't laziness or apathy—it's evolution. Our brains developed a powerful preference for stability because, for our ancestors, change meant danger. That same neural wiring now keeps us trapped in jobs we've outgrown, relationships that no longer serve us, and health insurance plans that drain our wallets.

Recent research reveals the startling power of this bias: In Austria, where organ donation is opt-out, over 90% of people are registered donors. Just across the border in Germany, where donation is opt-in, fewer than 15% register. Same people, same values, different defaults—radically different outcomes.

When your great-great-grandparents wandered the African savanna, trying something new could get you killed. That unfamiliar berry might be poisonous. That unexplored cave might house a predator. The brain evolved a simple rule: if it's working, don't mess with it.

This makes evolutionary sense when you consider the math of survival. For our ancestors, a 10% chance of finding slightly better food wasn't worth a 10% risk of death. Losses always mattered more than equivalent gains because losing meant you might not survive to reproduce. Modern behavioral economics confirms this: we experience losses roughly twice as intensely as equivalent gains.

For early humans, avoiding losses was literally a matter of survival. Today, that same instinct keeps us in mediocre jobs and expensive phone plans.

Even capuchin monkeys demonstrate this bias. In experiments at Yale, researchers trained monkeys to trade tokens for snacks. When offered a choice between a guaranteed single treat versus a gamble that might yield two treats or none, the monkeys chose the safe option 71% of the time. This wasn't learned behavior—it was hardwired preference for the familiar.

The evolutionary pressure was so strong that status quo bias became encoded not just in our behavior, but in our brain architecture itself.

Your resistance to change has a physical address in your brain. When neuroscientists use fMRI to watch people make decisions about whether to stick with defaults or switch to alternatives, specific regions light up in predictable patterns.

The amygdala, your brain's ancient alarm system, activates more strongly during loss anticipation than gain anticipation. The right posterior insula and ventral striatum join this neural chorus, creating what researchers call the "loss anticipation network". Every time you consider changing the status quo, this network fires up, generating an uncomfortable feeling that switching might be a mistake.

But here's what makes this bias particularly stubborn: the subthalamic nucleus (STN) acts as a control center for decision-making. Research published in PNAS found that the STN shows heightened activity when people reject defaults, especially during difficult decisions. In other words, your brain has to work harder to change than to stay put. The more complex the decision, the more your neural circuitry defaults to "let's just keep things as they are."

This isn't a bug in the system—it's a feature designed to conserve mental energy. Making decisions burns cognitive resources. In a world of limited information and endless choices, defaulting to the familiar is often the most efficient strategy.

Before we vilify status quo bias entirely, consider this: sometimes it's actually rational. When you're faced with choice overload, sticking with previous decisions that worked isn't foolish—it's smart resource management.

Dean et al.'s 2017 research and Nebel's 2015 study both found that status quo bias intensifies when deliberation costs are high or uncertainty is overwhelming. If you're navigating a dozen health insurance options with impenetrable jargon, staying with your current plan might be the most practical choice given your cognitive limitations.

"While status quo bias is frequently considered to be irrational, sticking to choices that worked in the past is often a safe and less difficult decision due to informational and cognitive limitations."

— Dean et al. and Nebel, Behavioral Economics Research

This concept, called bounded rationality, acknowledges that humans rarely have perfect information or unlimited processing power. Sometimes the devil you know really is better than the devil you don't—not because the current state is objectively superior, but because the cost of evaluating alternatives exceeds the potential benefit.

The challenge comes when environments change faster than our assessment of whether inertia still serves us.

Status quo bias extracts a steep price in modern life. Consider retirement savings: when companies make 401(k) enrollment the default rather than opt-in, participation rates soar. The famous Save More Tomorrow program leverages this by automatically increasing contribution rates with each salary raise. Employees barely notice because they never experience the increased contribution as a "loss" from their paycheck.

But defaults cut both ways. Research on university health plan enrollment revealed a striking pattern: a new plan offered significantly better premiums and deductibles, and it steadily gained market share among new employees. Yet among existing enrollees, adoption rates remained stubbornly low. These weren't ignorant people—they had access to the same information. They simply couldn't overcome the pull of their current selection.

The insurance industry has long exploited this. When New Jersey and Pennsylvania offered drivers two insurance options with different defaults, only 20-25% of people switched from whichever option was initially set as the default, even when the alternative was objectively better for their circumstances.

In a California study on electric power reliability, 60.2% of customers chose to stick with their current high-reliability service, while only 5.7% opted for the low-reliability alternative. But here's the kicker: when researchers reversed which option was the default, the percentages flipped. People weren't choosing based on what they actually wanted—they were choosing whatever required no action.

Status quo bias isn't a single phenomenon but rather a convergence of multiple psychological forces, each reinforcing the others.

Loss aversion forms the foundation. Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky's pioneering work on prospect theory showed that losses loom larger than gains in our mental calculus. When you contemplate switching phone carriers, your brain fixates on what might go wrong—service gaps, hassle with porting numbers, potential hidden fees—while downplaying the savings you'd gain.

The endowment effect magnifies this. We overvalue things simply because we possess them. Your current coffee maker isn't objectively better than alternatives, but owning it creates an irrational attachment.

Cognitive inertia adds another layer. Evaluating new options requires mental effort, and brains are inherently lazy in the most efficient sense. As one source explains, "studying and weighing new ideas or alternatives requires mental effort" that we'd rather conserve for genuine threats.

Regret avoidance closes the loop. If you switch and it goes wrong, you'll feel personally responsible. If you stick with the current option and it disappoints, well, that's just how things are. The asymmetry in anticipated regret keeps us anchored.

Sunk cost thinking whispers that you've already invested time and effort in your current choice. Abandoning it now would mean admitting that investment was wasted, and your ego recoils from that admission.

Your brain isn't sabotaging you—it's trying to save energy. The problem is that the shortcuts that kept your ancestors alive can trap you in mediocrity today.

Together, these mechanisms create a powerful gravitational pull toward inaction. And here's the most insidious part: you probably won't even notice it's happening.

Status quo bias doesn't just affect individuals—it permeates organizations with even more destructive consequences. Companies continue holding annual performance reviews despite research showing that frequent feedback improves performance more effectively. Why? Because "that's how we've always done it."

This organizational inertia compounds because status quo bias operates at multiple levels simultaneously. Individual employees resist changing their routines. Managers hesitate to overhaul processes they implemented. Executives worry about the optics of admitting the current approach isn't optimal. Each layer of resistance reinforces the others.

The technology sector offers particularly stark examples. Market leaders with dominant products often fail to innovate, not from lack of resources or talent, but from psychological commitment to what made them successful. Kodak invented the digital camera in 1975 but couldn't abandon its film business. Nokia dominated mobile phones but missed the smartphone revolution. These weren't failures of imagination but triumphs of status quo bias.

The pattern repeats across industries: taxi companies ignoring ride-sharing, retailers dismissing e-commerce, media companies clinging to advertising models as audiences migrated to streaming. In each case, decision-makers had data showing the need for change. But institutional status quo bias created organizational paralysis until disruption became unavoidable.

Status quo bias has profound implications for governance and social progress. Electoral systems demonstrate this starkly: incumbent politicians enjoy substantial advantages not because they govern better, but because voters default to familiar names. Political scientist studies show that incumbency alone boosts vote share by 5-10 percentage points, even controlling for party affiliation and performance.

Constitutional design faces similar inertia. The U.S. Constitution's amendment process is deliberately difficult, requiring supermajorities to change. While this prevents hasty modifications, it also means outdated provisions persist long after their usefulness expires. The Electoral College, Senate apportionment, and other structural elements remain unchanged not because they're optimal, but because changing them requires overcoming both procedural hurdles and psychological resistance.

Policy default settings have massive ripple effects. When governments set defaults for organ donation, retirement savings, or energy plans, they're not just simplifying administration—they're determining outcomes for millions who will never actively reconsider those choices. This raises ethical questions about paternalism and autonomy that society is only beginning to grapple with.

Climate change represents perhaps the ultimate status quo bias challenge. Despite overwhelming evidence that current energy systems are unsustainable, individuals and institutions resist the wholesale changes needed because the status quo is comfortable and the alternative requires confronting uncertainty. The bias operates at every level: consumers stick with gas-powered cars, utilities maintain fossil fuel infrastructure, governments delay regulation. Each delay compounds the problem.

Here's a sobering finding: simply knowing about status quo bias doesn't eliminate it. Studies show that even when researchers explicitly inform participants about defaults and their psychological effects, the bias persists at nearly full strength.

This makes intuitive sense when you consider the mechanisms involved. Loss aversion isn't a thought you can simply think your way out of—it's how your amygdala responds to potential losses. The STN doesn't consult your conscious mind before making switching decisions cognitively expensive.

"The more difficult the decision we face, the more likely we are not to act."

— PNAS Study on Neural Decision-Making

Education helps at the margins, particularly by creating awareness that prompts occasional review of defaults. But expecting people to constantly override their neural architecture is unrealistic. Your brain evolved over millions of years to conserve energy and avoid risk. A few decades of behavioral economics research won't reprogram those fundamentals.

This is why interventions focused on changing defaults rather than changing minds prove so much more effective. When the UK switched workplace pensions from opt-in to opt-out, they didn't need to convince anyone that saving for retirement was wise—they just removed the action required to start saving.

The implication: if you want people to make better choices, don't try to eliminate status quo bias. Design systems where the default is the optimal choice.

Since you can't eliminate status quo bias, the goal becomes recognizing when it serves you versus when it holds you back. This requires developing what we might call "meta-cognitive awareness"—the ability to notice when you're defaulting rather than deciding.

Create forcing functions for periodic review. Set calendar reminders to reassess major recurring expenses annually. When the reminder pops up, you're prompted to actively choose to continue rather than passively accepting the status quo. This simple trick exploits a loophole: while starting the review process requires activation energy, once you're examining alternatives, present bias works in your favor.

Flip your framing from "should I switch?" to "if I were starting fresh today, what would I choose?" This mental reset strips away the endowment effect. You're no longer considering whether to abandon your current option, but rather which option you'd select without history. Research in decision-making shows this reframing significantly reduces status quo bias.

Use pre-commitment devices to automate future changes. The Save More Tomorrow program works precisely because it removes the repeated choice. You decide once to increase contributions with raises, then the system handles implementation. Consider where you might apply similar logic: automatic bill comparisons, scheduled portfolio rebalancing, preset relationship check-ins.

Seek out "forcing decisions" that require active choice. Some companies now use "active choice" systems rather than defaults, requiring employees to explicitly select 401(k) contribution levels rather than accepting a preset option. While this increases the cognitive load, it ensures the final decision reflects genuine preference rather than inertia.

Implement "kill criteria" upfront. Before committing to a course of action, define specific conditions that would trigger reconsideration. "If my insurance premium increases more than 10%, I'll comparison shop." "If my commute exceeds 45 minutes, I'll explore moving closer or changing jobs." These predetermined thresholds create objective triggers that bypass emotional attachment to the status quo.

Build in "sunset provisions" for major decisions. Instead of open-ended commitments, put expiration dates on choices. "I'll try this gym membership for three months, then decide whether to continue." Time limits transform potentially permanent defaults into temporary experiments, making it psychologically easier to change course.

As we've discovered how powerfully defaults shape behavior, a fascinating tension has emerged: who gets to set them? When governments or corporations design choice architecture, they wield enormous influence over outcomes, even if people retain theoretical freedom to opt out.

Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein coined the term "libertarian paternalism" to describe this approach: structuring choices to nudge people toward beneficial outcomes while preserving freedom. But as one researcher notes, "People will not voluntarily do what is in their best interest, so we should nudge them, but it must always be possible to opt out."

This raises profound questions. Should retirement plans default to high savings rates because we know most people undersave? Should organ donation be opt-out because we know most people support donation but never get around to registering? Should energy plans default to renewable sources because climate change demands urgent action?

Each question involves trading off autonomy against outcomes. Pure choice maximalists argue that any default represents manipulation, even when done with good intentions. Pragmatists counter that since some default must exist in any system, and since people will inevitably be influenced by it, why not make the default beneficial?

Every system has a default setting. The question isn't whether defaults influence behavior—they always do. The question is: who decides what the defaults should be?

The corporate context adds another layer. Companies increasingly use defaults to serve business interests rather than consumer welfare. Subscription services default to auto-renewal. Privacy settings default to maximum data sharing. Merchant websites pre-select the most expensive shipping option. These exploitative defaults prey on the same psychological mechanisms that beneficial defaults leverage.

Society needs robust frameworks for distinguishing legitimate nudges from manipulative dark patterns. Transparency helps—people should know they're being influenced and why. Regular review of defaults matters—what made sense five years ago may not today. And critically, opt-out mechanisms must remain genuinely accessible, not buried behind obstacles.

While status quo bias appears universal, its intensity varies across cultures in ways that reveal how social conditioning interacts with evolved psychology. Research in cross-cultural psychology suggests that individualistic Western societies may actually experience somewhat lower status quo bias than collectivist cultures, though the effect still remains strong everywhere.

In societies that emphasize social harmony and tradition, questioning established ways carries additional costs beyond individual cognitive effort. Changing course might disrupt group cohesion or challenge respected elders. The bias compounds: individual loss aversion plus social conformity plus cultural reverence for tradition.

Conversely, cultures that celebrate innovation and disruption may provide partial psychological insulation against status quo bias. If "moving fast and breaking things" is valorized, the anticipated regret of changing flips: you might feel worse about staying put than switching. Silicon Valley's fetishization of "disruption" can be understood as a cultural counter-balance to innate status quo bias, though it often overcorrects into change for change's sake.

Economic context matters too. In environments of scarcity and uncertainty, status quo bias intensifies as a risk-management strategy. When you're operating close to subsistence, experimentation becomes genuinely dangerous. Prosperous societies with strong safety nets afford people more latitude to overcome bias because the downside of mistakes is contained.

Status quo bias strengthens as we get older, and not just because we accumulate more habits. Multiple mechanisms converge with age. Cognitive resources decline, making the mental effort of evaluating alternatives more taxing. Risk tolerance decreases as time horizons shorten—why gamble on uncertain benefits when you have fewer years to recover from potential losses?

The health insurance data mentioned earlier showed this starkly: older enrollees persistently stuck with suboptimal plans despite clear information about superior alternatives. This wasn't ignorance or incompetence but rational energy conservation coupled with heightened loss aversion.

There's also a self-fulfilling element. As people age and accumulate commitments, the objective costs of change genuinely increase. It's easier to relocate for a better job opportunity at 25 than at 55 when you have a mortgage, kids in school, and deep community ties. This creates a feedback loop where experience of high switching costs reinforces psychological resistance.

Yet this isn't inevitable. Societies could design better support structures for life transitions at any age. The fact that career changes after 50 feel impossibly difficult reflects policy choices about retirement savings portability and healthcare access as much as it reflects immutable psychology.

Your brain's preference for stability made perfect sense in the environment where it evolved. For most of human history, the biggest threat was obvious and immediate—predators, starvation, hostile tribes. The slow accumulation of suboptimal choices barely registered against these acute dangers.

Modern life inverts this calculus. You're unlikely to be eaten by a tiger because you switched dentists. But you might significantly harm your long-term wellbeing by never reconsidering your 401(k) allocation, healthcare plan, or career path. The brain that protected your ancestors can become a cage in contemporary contexts.

This doesn't mean you should fight every instance of status quo bias. That would be exhausting and counterproductive. Some defaults serve you well. The goal is developing discernment about when inertia aligns with your actual interests versus when it's merely comfortable.

Think of it like this: your brain runs on heuristics—mental shortcuts that usually work. Status quo bias is one of those shortcuts. Most of the time, trusting it conserves energy for more important decisions. But in high-stakes domains where circumstances change—finances, health, career, relationships—you need override mechanisms to ensure your defaults still make sense.

The challenge of the 21st century isn't eliminating our evolutionary inheritance but learning to recognize when ancestral instincts clash with current reality. We're the first humans in history forced to consciously manage cognitive biases that previously operated invisibly. That metacognitive awareness—thinking about how we think—might be the defining skill of modern life.

Your brain will keep preferring stability. That's hardwired and it's not changing. But you can build systems, structures, and habits that work with this bias rather than against it. Set better defaults. Create forcing functions for review. Design choice architecture that serves your long-term interests.

Because here's the thing: status quo bias isn't going anywhere. The question is whether you'll let it run on autopilot or take the wheel occasionally to check if you're still headed where you want to go.

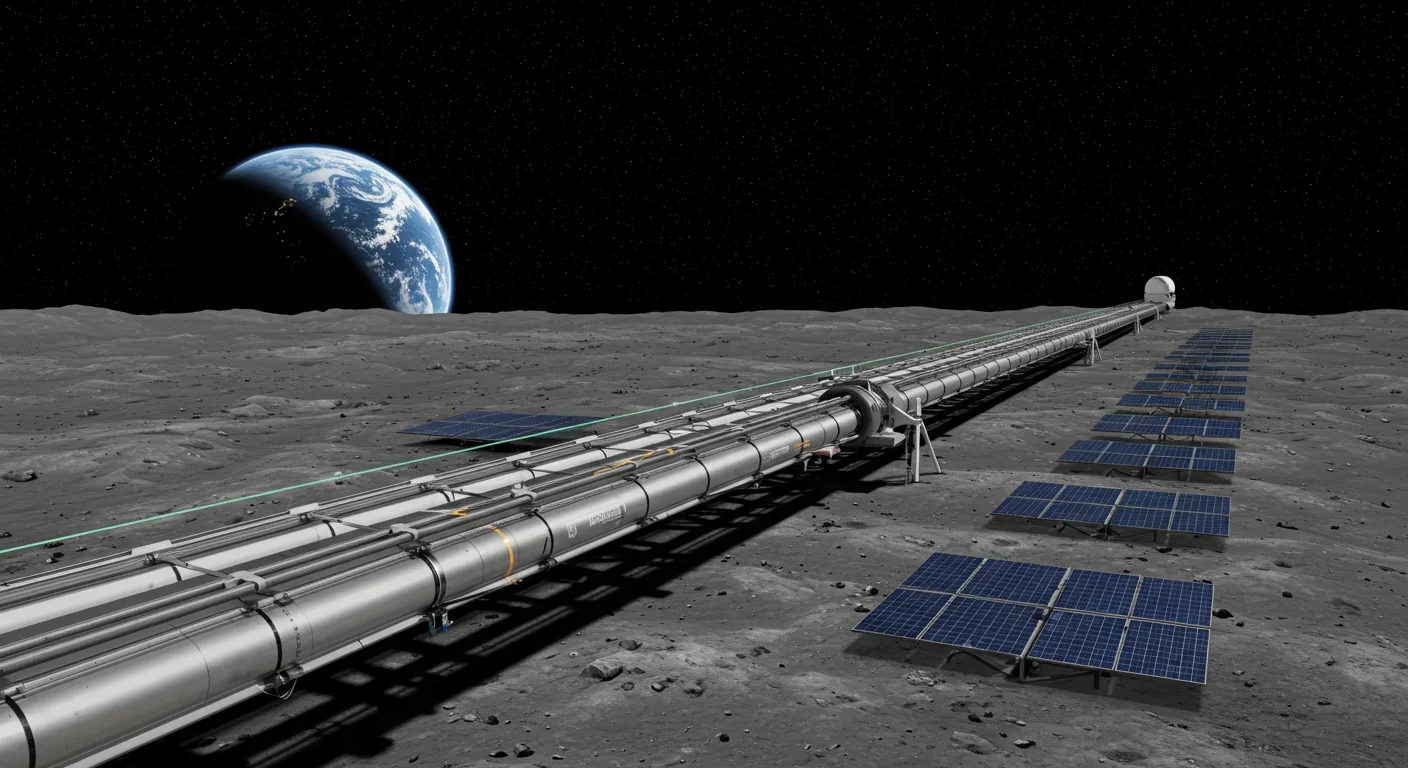

Lunar mass drivers—electromagnetic catapults that launch cargo from the Moon without fuel—could slash space transportation costs from thousands to under $100 per kilogram. This technology would enable affordable space construction, fuel depots, and deep space missions using lunar materials, potentially operational by the 2040s.

Ancient microorganisms called archaea inhabit your gut and perform unique metabolic functions that bacteria cannot, including methane production that enhances nutrient extraction. These primordial partners may influence longevity and offer new therapeutic targets.

CAES stores excess renewable energy by compressing air in underground caverns, then releases it through turbines during peak demand. New advanced adiabatic systems achieve 70%+ efficiency, making this decades-old technology suddenly competitive for long-duration grid storage.

Human children evolved to be raised by multiple caregivers—grandparents, siblings, and community members—not just two parents. Research shows alloparenting reduces parental burnout, improves child development, and is the biological norm across cultures.

Soft corals have weaponized their symbiotic algae to produce potent chemical defenses, creating compounds with revolutionary pharmaceutical potential while reshaping our understanding of marine ecosystems facing climate change.

Generation Z is the first cohort to come of age amid a polycrisis - interconnected global failures spanning climate, economy, democracy, and health. This cascading reality is fundamentally reshaping how young people think, plan their lives, and organize for change.

Zero-trust security eliminates implicit network trust by requiring continuous verification of every access request. Organizations are rapidly adopting this architecture to address cloud computing, remote work, and sophisticated threats that rendered perimeter defenses obsolete.