The Hidden Memory Trap: Why Your Ideas Aren't Original

TL;DR: Humans deliberately waste resources through conspicuous consumption, excessive credentials, and elaborate rituals to prove qualities like wealth, intelligence, and commitment. This costly signaling works because genuine displays are too expensive to fake, but creates arms races where everyone invests more just to maintain their relative position.

Every day, people spend thousands on handbags that hold the same amount as a $20 tote. Others pursue PhDs that won't increase their salary. Companies host lavish parties instead of giving employees bonuses. These behaviors seem irrational, but they follow a precise evolutionary logic that shapes everything from peacock feathers to Instagram posts.

This is costly signaling: the practice of deliberately wasting resources to demonstrate qualities that are otherwise hidden. The waste isn't accidental—it's the entire point. In a world where anyone can claim to be wealthy, intelligent, or committed, only genuine displays that hurt to fake can be trusted.

The story begins in 1975 when Israeli biologist Amotz Zahavi proposed the handicap principle. He noticed that male peacocks grew tails so elaborate they could barely fly. Darwin had explained these ornaments as products of female preference, but Zahavi asked: why would females prefer such obviously terrible traits?

His answer revolutionized biology. The tail works because it's terrible. A peacock with a massive tail is advertising: "I'm so fit I can survive even with this ridiculous handicap." Only truly healthy birds can afford the energy to grow and maintain such plumage. The peacock's tail both increases vulnerability to predators and requires more energy for maintenance, making it a genuine cost that weak birds cannot fake.

Biologists initially rejected Zahavi's theory. It seemed absurd that evolution would favor waste. But mathematical models eventually proved him right. Signals work precisely because they are costly. If they were cheap, everyone would fake them, and they'd convey no information.

This same logic governs human behavior in ways we rarely recognize.

Costly signals work precisely because they're expensive. If anyone could afford them, they'd reveal nothing about the sender.

Two years before Zahavi published his biological theory, economist Michael Spence was developing a parallel insight about education. His 1973 paper "Job Market Signaling" asked a provocative question: what if college doesn't make you smarter, but simply proves you already were?

Spence's model demonstrated that education can be an effective signal even when it doesn't directly increase job performance. The key is differential cost. Earning a degree requires intelligence, conscientiousness, and family resources. These are the exact qualities employers want, but can't observe directly in a job interview.

Because high-ability workers find school less difficult than low-ability workers, they can afford to acquire credentials that others cannot. The degree doesn't have to teach useful skills—it just has to be expensive enough that only the right people can obtain it. Spence's 1974 book Market Signaling explicitly argues that educational credentials can serve as a signal even if they do not enhance actual productivity.

The implications are startling. The wage premium associated with completing a degree compared to just studying the same number of years—the "sheepskin effect"—can be as large as 10-20% in some labor markets. You don't get paid for what you learned; you get paid for the certificate proving you could endure the process.

Spence won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics in 2001 for this work, which transformed how economists understand information asymmetry in markets.

If credentials work as signals, more people will pursue them. But as more people earn degrees, the signal loses its power to distinguish the best candidates. So employers start requiring master's degrees. Then everyone gets master's degrees. Soon you need a PhD for jobs that once required a bachelor's.

This is credential inflation, and it's happening worldwide. UNESCO data shows that the number of higher education graduates globally doubled over the last two decades. Yet employers still struggle to find qualified workers, and over 45% of EU workers possess skills that do not match their jobs, indicating severe skills mismatch.

The costs are staggering. Students spend years acquiring credentials they don't need for the work they'll do. English workers reporting overqualification earn almost 18% less than peers appropriately matched to their roles. Universities expand programs not because they improve education, but because they generate revenue. Harvard's on-campus indirect cost rate is 69 percent, the highest among major universities—meaning research grants primarily fund institutional overhead.

The system persists because no individual can opt out. If everyone else has a master's degree, not having one marks you as less capable, regardless of your actual skills. Economic models demonstrate that signaling equilibria can lead to socially wasteful outcomes even when individually rational.

"Education can be a purely informational signal, costly but without direct skill training value."

— Michael Spence, Market Signaling

We're trapped in what biologists call an "arms race"—everyone keeps investing more to maintain their relative position, but nobody gains an absolute advantage. The total cost rises without producing additional value.

Thorstein Veblen recognized costly signaling in 1899, though he didn't use that term. His book The Theory of the Leisure Class introduced conspicuous consumption: the practice of purchasing goods to publicly display wealth rather than meet needs.

Veblen observed that the wealthy didn't just spend money—they wasted it visibly. They wore impractical clothing that required servants to maintain. They hosted elaborate dinners where most food was thrown away. They built mansions too large to use efficiently. The waste was the point. It proved they could afford to be wasteful.

This pattern extends far back. During the Roman Empire, Mark Antony used exotic animals, actresses, and custom chariots to exhibit his status. Ancient Chinese elites showcased wealth through extravagant feasts and elaborate clothing. The cross-cultural universality suggests deep evolutionary roots.

Modern luxury goods operate on identical principles. Veblen goods are products where demand increases as price increases, in apparent violation of economic law. A handbag becomes more desirable precisely because it costs $10,000 instead of $100. The high price makes it a more credible signal of wealth.

Marketing strategically enhances the perceived costliness of luxury goods, making them more effective signals. Brands carefully control distribution, destroy unsold inventory, and advertise exclusivity. They're not selling bags—they're selling proof of wealth that's hard to fake.

Veblen goods exhibit an income elasticity of demand greater than one, meaning a 10% price increase can lead to more than a 10% rise in quantity demanded among affluent consumers. The economics seem backwards until you understand that the high price is the product.

Social media has turbocharged conspicuous consumption by dramatically increasing the audience for signals. Historically, you could only signal to people who saw you in person—a few hundred individuals at most. Now platforms like Instagram and TikTok amplify the visibility of luxury goods and lifestyles, creating a culture of aspiration that transcends geographical boundaries.

Chinese university students are among the youngest consumers of luxury goods, with individuals aged 21-25 making their first luxury purchases before turning 20. Many explicitly state they buy these goods to post about them online. The purchase isn't the signal—the Instagram post is.

This creates perverse incentives. People go into debt to afford displays they can't sustain. They rent luxury items for photoshoots. They vacation in expensive locations but stay in cheap hotels, spending their budget on a few photos at recognizable landmarks.

The behavior makes sense once you understand costly signaling. Social media success increasingly determines economic opportunity. Influencers earn money from their perceived status. Even in traditional careers, a strong online presence can lead to better opportunities. For many young people, luxury consumption on social media is an investment strategy, not pure vanity.

But the arms race dynamic applies here too. As more people adopt luxury signaling, each individual must spend more to stand out. The threshold for "impressive" keeps rising. What was once extraordinary becomes expected, and the pressure to escalate intensifies.

On social media, the Instagram post of a luxury item is often more valuable than the item itself. The signal reaches thousands instead of dozens.

Not all costly signals are created equal. Some reliably indicate the quality they claim to represent. Others are increasingly easy to fake as technology improves.

Honest signals share several characteristics. First, the cost must be negatively correlated with the quality being signaled. Education works because smart people find it easier. Athletic achievement works because fit people train more efficiently. If everyone faced the same cost, the signal would reveal nothing.

Second, the cost must be hard to fake. Zahavi's handicap principle works because you can't fake a magnificent tail without actually being healthy enough to grow one. Fake signals that approach the cost of real ones defeat their own purpose.

Third, there must be a mechanism that punishes cheaters. In biology, weak peacocks who try to grow elaborate tails die. In economics, students who can't handle coursework drop out. The punishment for faking signals helps maintain honesty.

But technology undermines these mechanisms. Photo editing makes it trivial to fake luxury lifestyle photos. Credential mills sell fake degrees. Bots inflate social media metrics. As signals become easier to fake, they lose value—but only after many people waste resources trying to send them.

The article claims that deceptive signaling can arise as an arms race where signalers continually raise signal costs to maintain honesty. This creates a Red Queen dynamic: everyone must keep investing just to stay in place.

Beyond wealth and ability, humans also need to signal commitment—to relationships, groups, and ideologies. This is where rituals become costly signals.

Religious rituals are particularly illustrative. Fasting during Ramadan, keeping kosher, attending weekly services—these practices require time and sacrifice. They signal commitment to the faith community in a way that's hard for casual believers to fake.

Research shows these signals have tangible benefits. Alloparenting support is higher for women attending church at least yearly, leading to more children and potentially better child cognitive outcomes. The ritual attendance signals commitment to the community, which responds with reciprocal support.

Weddings function similarly. The traditional wedding costs tens of thousands of dollars and requires months of planning. This seems wasteful, but it serves as a costly signal of commitment to the relationship. Both partners demonstrate willingness to invest substantial resources, making casual or opportunistic pairing less likely.

Many cultural practices that appear arbitrary are actually sophisticated commitment mechanisms. Initiation rites, graduation ceremonies, citizenship oaths—all use cost and publicity to create credible signals of membership and dedication.

The effectiveness of rituals depends on their costliness remaining calibrated to what participants can afford. If rituals become too expensive, they exclude genuine members. If they become too cheap, they lose signaling value and the community's cohesion weakens.

"Ritual attendance signals commitment to the community, which responds with reciprocal support—a practical benefit of costly signaling."

— Center for Mind and Culture Research

The logic of costly signaling explains many puzzling behaviors, but it also reveals deeply inefficient aspects of modern society. We've created systems where enormous resources are wasted not producing value, but merely sorting people.

Consider military spending, which often functions as costly signaling between nations. The Australian Department of Defence spent an estimated AUD 79 million in unnecessary expenditure on maintenance of Admiral frigates, inflating costs from AUD 72 million to AUD 170 million. The waste occurred not from incompetence, but from systemic incentives to inflate military capability signals.

Environmental damage from conspicuous consumption represents another failure mode. Veblen goods are viewed as deadweight loss with significant ethical concerns about their wastefulness. Luxury products often have enormous carbon footprints and encourage resource depletion for purely symbolic purposes.

The credential arms race imposes massive costs on young people. Student debt in the United States exceeds $1.7 trillion. Millions of people spend their twenties acquiring credentials for jobs they could have performed at eighteen, simply because everyone else is doing the same. Parents who view elite education as an appreciating asset see it as an investment strategy rather than education, perpetuating inequality.

These are textbook examples of coordination failures. Everyone would be better off if we collectively agreed to reduce signaling intensity. But without enforcement mechanisms, individuals who unilaterally reduce their signaling are simply outcompeted by those who don't.

While costly signaling is universal, its specific forms vary dramatically across cultures. What counts as an impressive signal depends entirely on local context and values.

In many East Asian cultures, educational credentials carry especially strong signaling value. Chinese university students make their first luxury purchases before turning 20, but they're equally likely to signal through academic achievement. The gaokao exam in China determines university placement and life trajectory, making test preparation itself a costly signal of family dedication.

Some indigenous cultures use dramatically different signals. Potlatch ceremonies in Pacific Northwest indigenous communities involved giving away or destroying accumulated wealth. The most prestigious members were those who could afford to give away the most—a costly signal of resource abundance that simultaneously prevented excessive inequality.

In some Northern European cultures, conspicuous consumption is actively stigmatized. The Swedish concept of lagom (not too much, not too little) and Danish janteloven (law of Jante) discourage status displays. But costly signaling doesn't disappear—it just takes different forms. Environmental consciousness, minimalist aesthetics, and humble-bragging about simple lifestyles become the signals instead.

These variations demonstrate that while the underlying logic of costly signaling is universal, its applications are culturally constructed. We learn what signals matter in our specific social context, and we compete on those dimensions.

Why do humans care so much about status that we'll waste resources to display it? The answer lies in our evolutionary history and brain architecture.

Studies in 2007 showed that social comparison affects reward-related brain activity, providing evidence that people derive psychological benefits from status displays. We're not just pretending to care—our brains are wired to find status intrinsically rewarding.

This makes evolutionary sense. For most of human history, status was closely tied to survival and reproductive success. High-status individuals had better access to food, mates, and resources for their offspring. Our ancestors who pursued status effectively left more descendants, and we inherited their status-seeking psychology.

But modern environments create mismatches. Our brains evolved in small groups where status competitions had clear winners and losers. Today we can compare ourselves to billions of people via the internet, creating unwinnable status races. We're running ancestral software on modern hardware, and it's making us miserable.

The research on costly signaling helps explain phenomena like the "hedonic treadmill"—why more wealth doesn't make us proportionally happier. If much of our consumption is about relative status rather than absolute welfare, then population-wide increases in wealth don't improve anyone's position. We all run faster just to stay in place.

Our brains evolved to seek status in groups of 150 people. Now we compare ourselves to billions online—an evolutionary mismatch driving modern anxiety.

Understanding costly signaling theory doesn't make you immune to it, but it does provide a useful framework for navigating modern life more effectively.

First, recognize that many of your intuitions about what you "need" are actually about signaling. That anxiety about wearing the same outfit twice to work? Signaling. The pressure to attend a prestigious university even if a cheaper option provides equal education? Signaling. The urge to post vacation photos? You get the idea.

Second, consider which signals actually matter for your goals. If you're pursuing a creative career, luxury goods might be poor signals compared to a portfolio of work. If you're building a business, credentials matter less than proven results. Ruthlessly cut signals that aren't serving your actual objectives.

Third, look for undervalued signals. When everyone competes on the same dimension, costs escalate without providing an advantage. Finding signals that effectively demonstrate your qualities but aren't yet overcrowded gives you better returns on investment.

Fourth, build genuine capabilities rather than just signaling. Spence's model works because education correlates with ability, even if it doesn't cause it. If you focus on developing real skills, appropriate signals often follow naturally. The reverse rarely works—signals without substance are increasingly easy to detect.

Finally, consider collective action. Many signaling arms races make everyone worse off, but individuals can't unilaterally stop competing without being penalized. This is precisely where regulation, professional norms, or community standards can help. Dress codes, sumptuary laws, and credential reforms all attempt to limit wasteful signaling competition.

Technology is rapidly changing the landscape of costly signaling in ways we're only beginning to understand.

Artificial intelligence threatens to disrupt educational signaling. If AI can perform most cognitive tasks, what does a college degree signal? The answer may shift from "I can do intellectual work" to "I'm disciplined enough to complete a multi-year commitment" or "I had the resources and social capital to attend college." The signal persists, but its meaning changes.

Digital credentials and blockchain verification could reduce credential fraud, making educational signals more honest but potentially more stratified. If degrees become impossible to fake, their signaling value might increase—but so would pressure to obtain them.

Social media continues evolving rapidly. Early platforms rewarded conspicuous displays, but newer platforms emphasize different signals. TikTok rewards creativity and cultural fluency more than luxury goods. BeReal punishes the curated perfection that Instagram encourages. As platforms change, so do the optimal signaling strategies.

Climate change may force a rethinking of conspicuous consumption. As environmental consciousness increases, some luxury goods lose signaling value. Private jets and gas-guzzling cars transition from status symbols to targets of criticism. But the fundamental drive to signal doesn't disappear—it just finds new channels. Environmental virtue signaling through electric vehicles, solar panels, or sustainably sourced products follows the same logic.

Wealth inequality intensifies signaling competitions at every level. As the gap between rich and poor widens, signals that effectively distinguish status become more valuable. The ultra-wealthy develop increasingly elaborate displays that separate them from the merely rich. Meanwhile, middle-class signaling becomes more desperate as economic anxiety increases.

Costly signaling theory offers an intriguing lens through which we can view human behavior, relationships, and social structures. It explains why we engage in behaviors that seem irrational when viewed individually but make perfect sense in a competitive social environment.

The theory reveals uncomfortable truths. Much of what we call meritocracy is actually about access to expensive signals. Educational credentials don't primarily certify knowledge—they prove you could afford the process. Conspicuous consumption doesn't demonstrate refined taste—it proves you can waste resources.

But understanding these dynamics also points toward solutions. When we recognize signaling arms races, we can design institutions that reduce wasteful competition. We can develop alternative signals that more directly measure what we care about. We can opt out of competitions that don't serve our actual goals.

Most importantly, costly signaling theory helps us see past surface justifications to the underlying evolutionary logic driving behavior. People who buy luxury goods aren't stupid—they're responding rationally to social incentives. Students pursuing credentials they don't need aren't making mistakes—they're adapting to the signaling equilibrium of the job market.

Once you see the world through the lens of costly signaling, you can't unsee it. From architecture to fashion to social media behavior, the theory illuminates hidden patterns in human competition and cooperation.

The peacock's tail looks different once you understand it's not about beauty, but about survival. So do college degrees, wedding rings, and Instagram posts. They're all elaborate, expensive, and sometimes absurd displays that solve the same fundamental problem: proving you are who you claim to be in a world full of potential deceivers.

We're all peacocks, spreading our tails to signal fitness in the social marketplace. The challenge is learning which tails to grow—and which ones aren't worth the cost.

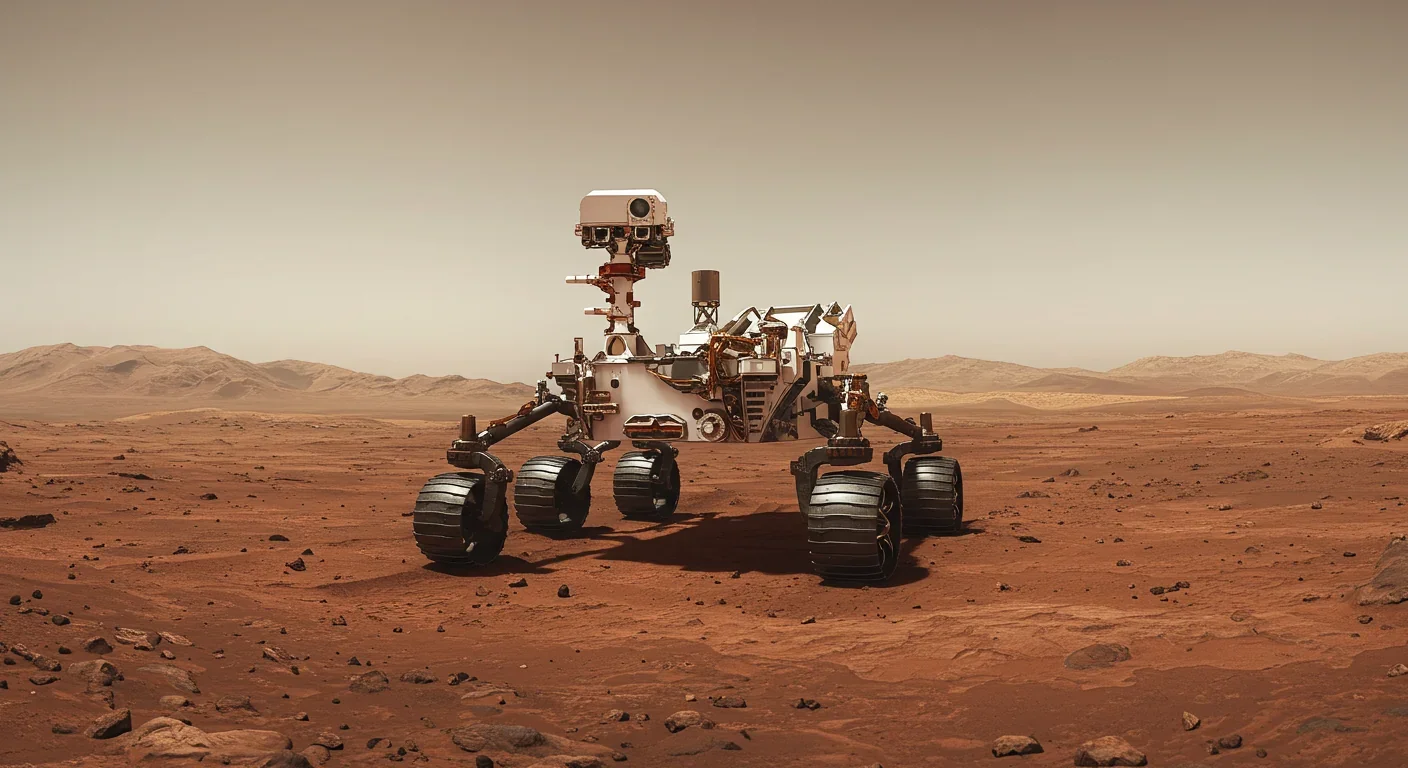

Curiosity rover detects mysterious methane spikes on Mars that vanish within hours, defying atmospheric models. Scientists debate whether the source is hidden microbial life or geological processes, while new research reveals UV-activated dust rapidly destroys the gas.

CMA is a selective cellular cleanup system that targets damaged proteins for degradation. As we age, CMA declines—leading to toxic protein accumulation and neurodegeneration. Scientists are developing therapies to restore CMA function and potentially prevent brain diseases.

Intercropping boosts farm yields by 20-50% by growing multiple crops together, using complementary resource use, nitrogen fixation, and pest suppression to build resilience against climate shocks while reducing costs.

Cryptomnesia—unconsciously reproducing ideas you've encountered before while believing them to be original—affects everyone from songwriters to academics. This article explores the neuroscience behind why our brains fail to flag recycled ideas and provides evidence-based strategies to protect your creative integrity.

Cuttlefish pass the marshmallow test by waiting up to 130 seconds for preferred food, demonstrating time perception and self-control with a radically different brain structure. This challenges assumptions about intelligence requiring vertebrate-type brains and suggests consciousness may be more widespread than previously thought.

Epistemic closure has fractured shared reality: algorithmic echo chambers and motivated reasoning trap us in separate information ecosystems where we can't agree on basic facts. This threatens democracy, public health coordination, and collective action on civilizational challenges. Solutions require platform accountability, media literacy, identity-bridging interventions, and cultural commitment to truth over tribalism.

Transformer architectures with self-attention mechanisms have completely replaced static word vectors like Word2Vec in NLP by generating contextual embeddings that adapt to word meaning based on surrounding context, enabling dramatic performance improvements across all language understanding tasks.