Why Evolution Designed Children to Need More Than Two Parents

TL;DR: Research shows we value products 63% more when we assemble them ourselves. The IKEA effect reveals how effort transforms ordinary items into prized possessions, influencing everything from furniture to finance.

Imagine paying 63% more for a wobbly bookshelf you assembled yourself than for an identical, professionally made version. Sounds irrational, right? Yet this is exactly what researchers discovered when they named the IKEA effect in 2011. The phenomenon reveals a fundamental quirk of human psychology: we place disproportionately high value on things we've partially created, even when they're objectively inferior to alternatives.

This cognitive bias doesn't just explain why that lopsided IKEA dresser feels like a personal triumph. It shapes consumer behavior across industries, influences marketing strategies worldwide, and affects everything from how we perceive homemade meals to why we cling to sunk costs. Understanding the IKEA effect means understanding why effort transforms our relationship with objects and why labor, not just results, drives how we assign value.

The IKEA effect emerged from a simple question: Why do people overvalue their own creations? In 2011, behavioral economists Michael I. Norton of Harvard Business School, Daniel Mochon of Yale, and Dan Ariely of Duke published groundbreaking research that gave this bias its name. Their experiments revealed something striking about human nature.

In their first study, participants who assembled simple IKEA furniture were willing to pay significantly more for their creations than those who examined pre-built versions. The premium? A whopping 63%. This wasn't about craftsmanship or quality since the items were identical. The difference was pure psychology.

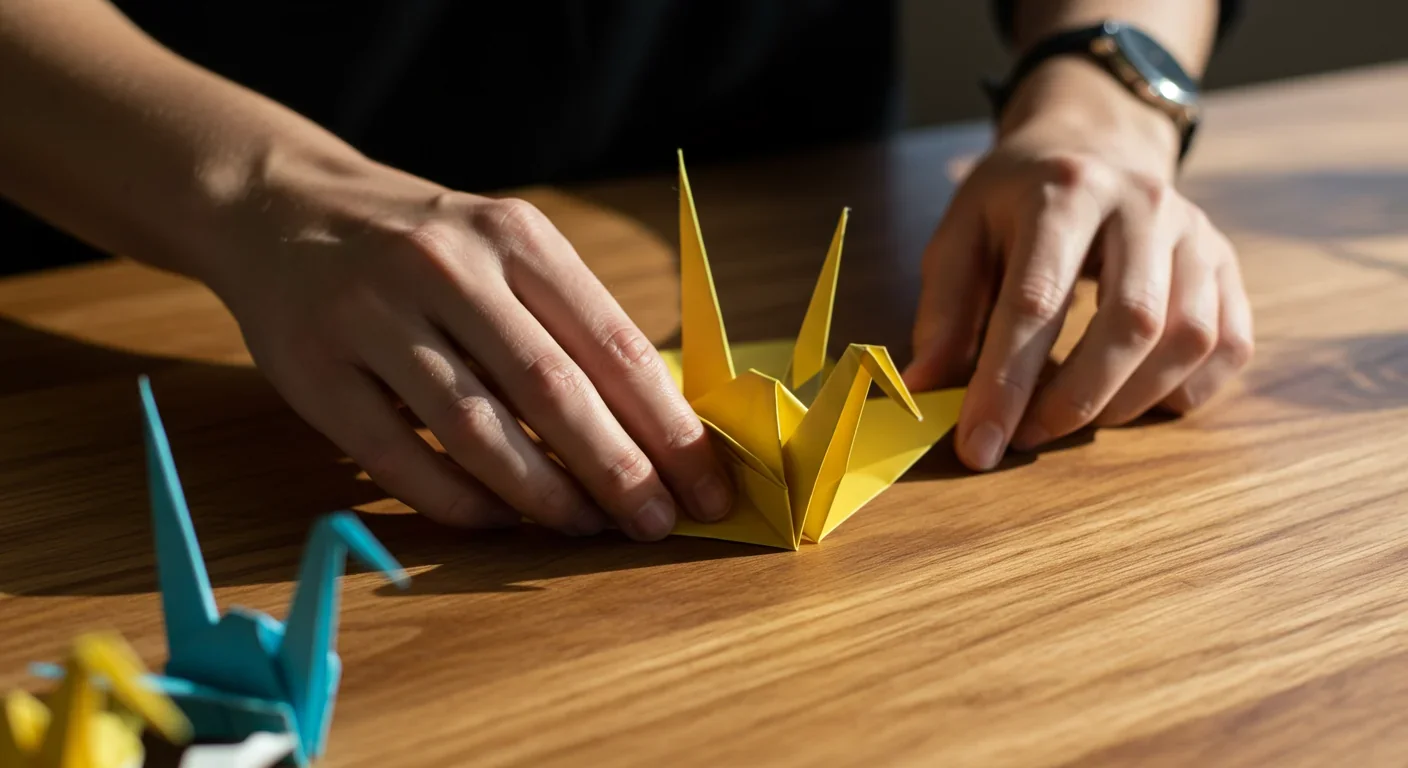

The researchers didn't stop there. They ran a second experiment using origami. Participants folded paper into basic shapes, then rated their creations. The results were remarkable: builders valued their amateur origami about five times higher than non-builders did. Even more telling, builders rated their clumsy paper cranes nearly as highly as expert-level origami. The labor itself had fundamentally altered perception.

Norton, Mochon, and Ariely's key finding: "labor alone can be sufficient to induce greater liking for the fruits of one's labor." The effort matters more than the outcome's objective quality.

Norton, Mochon, and Ariely summarized their findings with elegant simplicity: "labor alone can be sufficient to induce greater liking for the fruits of one's labor." This wasn't about the outcome's objective quality but the psychological transformation that happens when we invest effort.

Three interconnected psychological mechanisms drive the IKEA effect, each revealing different aspects of how our minds work.

Effort Justification and Cognitive Dissonance

At the core lies effort justification, a concept rooted in cognitive dissonance theory. When we invest time and energy into a task, our brains face an uncomfortable inconsistency: "I spent all this effort. Was it worthwhile?" To resolve this tension, we unconsciously inflate the value of what we created.

Leon Festinger's 1957 work on cognitive dissonance established the foundation. The classic demonstration came from Aronson and Mills in 1959. They asked college students to undergo either mild or severe embarrassment to join a discussion group. Those who endured the intense screening rated the group significantly higher than those with minimal effort, even though the discussion itself was deliberately boring. The effort alone created value where none objectively existed.

"If I suffered, it must've been worth it."

— Psychology researcher on effort justification

The same process operates when you assemble furniture. Your brain transforms struggle into worth, converting frustration into attachment. As one psychology researcher notes, "If I suffered, it must've been worth it." This isn't conscious calculation but automatic mental accounting.

Competence and Self-Perception

Successfully completing a task triggers feelings of competence. When you finish assembling that bookshelf, you're not just building furniture; you're proving to yourself that you can accomplish something concrete. This matters more than we realize.

The IKEA effect depends critically on successful completion. Norton's team found that when participants built items but then destroyed them, or failed to complete construction, the effect vanished entirely. Labor only leads to love when it results in achievement. Partial assembly or failure breaks the spell.

This reveals why difficulty matters. The task needs to be challenging enough to feel meaningful but achievable enough to complete. Too easy, and there's no competence boost. Too hard, and you're left with frustration instead of accomplishment. Companies designing DIY experiences walk this tightrope constantly.

Psychological Ownership

The act of creation establishes what psychologists call psychological ownership. When you physically manipulate materials and shape them into something, the object becomes "yours" in a way that transcends legal ownership. You've literally left your mark on it.

This connects to the broader effort heuristic, our mental rule of thumb that equates effort with quality. We judge objects that took longer to produce as inherently more valuable. Experiments show that people rate poems more highly when told the poet spent 18 hours writing instead of 4, even when the poems are identical.

Interestingly, this heuristic operates even when we should know better. Self-identified art experts relied on perceived effort just as much as novices when evaluating paintings. Expertise doesn't eliminate the bias; we're all susceptible to confusing effort with worth.

The business world caught on quickly. Once researchers demonstrated that consumers would pay premiums for products they partially created, companies across industries began engineering experiences to trigger the effect.

The Betty Crocker Revolution

The classic example predates the research by decades. In the 1950s, Betty Crocker struggled to sell instant cake mixes. The product was too convenient. Housewives felt like they were cheating, not cooking.

The solution? Remove powdered eggs from the mix and require customers to add fresh eggs themselves. This tiny modification transformed perception. Suddenly, bakers felt involved in the creation process. Sales soared. The mixes flew off shelves not despite requiring more effort but because of it. That single egg cracked open a new understanding of consumer psychology.

Build-a-Bear and the Premium for Participation

Build-a-Bear Workshop turned the IKEA effect into a complete business model. Children don't just buy stuffed animals; they stuff them, dress them, and create birth certificates. The process takes longer and costs more than buying a ready-made toy, yet parents happily pay the premium.

The company understood something crucial: the ceremony of creation matters as much as the product. Each station in the store adds another layer of psychological ownership. By the time kids leave, they're not carrying a generic teddy bear but a companion they built with their own hands.

The ceremony of creation matters as much as the product itself. Each step adds another layer of psychological ownership and attachment.

Digital DIY: Customization as Value Creation

Software companies discovered that customizable interfaces increase user attachment. When you spend time arranging your dashboard, selecting themes, or configuring settings, you're investing labor that transforms generic software into "your" tool.

Nike's custom shoe configurator, Starbucks' drink customization system, even adjustable features in productivity apps all leverage this principle. Each choice you make, each element you personalize, increases your valuation of the final product. You're not just a consumer; you're a co-creator.

Gaming takes this further. Minecraft and similar sandbox games are essentially IKEA effect engines, letting players invest hundreds of hours building virtual worlds they'll defend passionately. The games provide raw materials; players provide labor and reap the psychological rewards.

The bias extends far beyond consumer products, shaping behavior in education, finance, food, and creative work.

Educational Applications

Educators have started using the IKEA effect strategically. When students actively construct knowledge rather than passively receiving it, they value what they learn more highly. Project-based learning, hands-on experiments, and collaborative problem-solving all trigger the same psychological mechanisms as assembling furniture.

The effect explains why students remember material they struggled with more vividly than information that came easily. The effort becomes part of the learning, transforming abstract concepts into personally earned understanding. Teachers who understand this design assignments that require appropriate challenge and ensure successful completion.

Financial Decision-Making

In investing, the IKEA effect can be both tool and trap. Research by Ashtiani and colleagues in 2021 found that investors who participated in constructing their portfolios showed reduced panic selling during market downturns. The labor of selecting investments created attachment that provided emotional stability.

But the same mechanism drives sunk cost fallacies. Investors cling to losing positions because they've invested effort in the original decision. The research shows people are more cautious with hard-earned money than lottery winnings, suggesting that effort in acquiring resources affects how we value and deploy them.

Culinary Creations

The explosion of meal kit services like Blue Apron and HelloFresh taps directly into the IKEA effect. These companies could deliver fully prepared meals but deliberately don't. They provide pre-measured ingredients and instructions, requiring customers to perform the actual cooking.

This isn't inefficiency; it's strategy. Subscribers value meals more highly when they've chopped vegetables, stirred pots, and plated dishes themselves. The effort transforms a delivered service into a personal culinary achievement. You're not ordering takeout; you're cooking dinner.

Home brewing, sourdough baking, and DIY fermentation all benefit from the same psychology. The tedious processes these hobbies require aren't bugs but features, creating attachment through invested labor.

"The curse of authorship: The more time you spend on a project, the harder it becomes to see its flaws. Your labor has bonded you to the work, clouding objective assessment."

— Creative professionals on the IKEA effect

Creative Work and the Curse of Authorship

Writers, designers, and artists know the IKEA effect intimately, though they might not call it that. The phenomenon explains why creators struggle to edit their own work objectively. Every sentence, every design choice represents invested effort, making it psychologically painful to cut even when revision requires it.

This creates what some call the curse of authorship. The more time you spend on a project, the harder it becomes to see its flaws. Your labor has bonded you to the work, clouding objective assessment. Professional editors and designers combat this by separating themselves from their creations and seeking external feedback.

The IKEA effect isn't universal. Understanding when it fails reveals as much as knowing when it succeeds.

The Necessity of Completion

Perhaps the most critical boundary is task completion. The original research demonstrated that incomplete assembly eliminates the effect entirely. If you give up halfway through building that bookshelf, you won't value it more; you'll likely resent it.

This has practical implications for product design. Companies need to ensure their DIY experiences are achievable. If too many customers fail to complete assembly, the intended value enhancement backfires into frustration and negative brand perception. IKEA itself invests heavily in instruction clarity for this reason.

Destruction also kills the effect. When Norton's participants built origami and then had to tear it apart, the previously observed valuation premium disappeared. The tangible result matters. Without a completed artifact to show for your effort, the psychological mechanisms don't engage.

Arbitrary or Excessive Effort

Not all labor creates value. When effort feels meaningless or manipulative, the effect weakens or reverses. If customers perceive that they're doing work the company should handle simply to save costs, resentment replaces attachment.

There's also a ceiling. Extremely difficult or time-consuming tasks can overwhelm the competence boost and flip the effect negative. If assembling furniture requires professional tools and takes eight hours, most people won't feel accomplished; they'll feel exploited.

The research suggests that ambiguity amplifies the effort heuristic. When objective quality is hard to assess, we rely more heavily on perceived effort. But when a product is clearly substandard, no amount of invested labor can override direct evidence of poor quality.

Individual Differences

While the IKEA effect is robust across populations, individual variation exists. People high in need for competence show stronger effects. Those with perfectionist tendencies may experience reduced benefits if they're dissatisfied with their execution.

Cultural factors matter too. Societies that emphasize collective achievement over individual accomplishment may show different patterns. The effect appears strongest in contexts where personal agency and self-reliance are culturally valued.

Understanding the IKEA effect empowers both strategic thinking and critical awareness.

For Consumers: Awareness as Defense

Recognizing the bias helps counteract its influence on purchasing decisions. When you're willing to pay premium prices for customizable products or struggling to abandon projects you've invested effort in, pause and ask: "Am I valuing this because of its objective worth or because of my sunk costs?"

Structured reflection helps. Separate the process from the outcome. Would you buy this item if someone else had assembled it? Does the effort you've invested change the product's actual functionality? These questions can pierce through effort justification fog.

The anticipation of effort can trigger the bias even before you begin. Marketing that emphasizes how much you'll be involved in creation may be manipulating your valuation before you've touched the product. Awareness of this tactic provides psychological armor.

For Designers: Ethical Application

Product designers face ethical choices. The IKEA effect can genuinely enhance user satisfaction when applied thoughtfully, but it can also manipulate consumers into accepting inferior products or overpaying.

The ethical path involves creating DIY experiences that add genuine value: customization that improves fit, assembly that builds skills, participation that creates meaningful connection.

The ethical path involves creating DIY experiences that add genuine value. Customization that actually improves fit, assembly that builds useful skills, participation that creates meaningful connection—these applications respect consumer agency while leveraging psychological insight.

The unethical path uses the bias to mask poor quality, shift labor burdens unfairly, or inflate prices without corresponding value. When companies require customer effort purely to reduce costs while maintaining premium pricing, they're exploiting rather than serving their users.

Implications for Pricing Strategy

The research findings on willingness to pay create interesting pricing opportunities. Companies can potentially charge more for DIY versions than ready-made alternatives, inverting traditional assumptions about convenience premiums.

But this only works when the effort feels valuable rather than burdensome. The key is framing: present DIY not as cost-cutting but as value-adding. Emphasize the creative control, the skill development, the personal touch. Make the labor feel like a feature, not a bug.

The IKEA effect sits within a larger cultural shift toward experiences over products and participation over passive consumption.

The Maker Movement and DIY Culture

The explosion of maker spaces, craft breweries, and DIY tutorials reflects more than nostalgia for handwork. It represents a hunger for the psychological satisfaction that the IKEA effect describes. In an economy dominated by digital abstraction and service work, creating tangible objects with our own hands provides deeply satisfying competence feedback.

This helps explain why people increasingly seek hobbies involving physical creation: woodworking, pottery, gardening, cooking from scratch. The products themselves might be cheaper or better quality if purchased, but the process provides psychological value that consumption alone cannot.

Co-Creation as Business Model

Forward-thinking companies are moving beyond selling finished products toward facilitating co-creation. They provide platforms, tools, and raw materials, then step back and let customers do meaningful work. The customers pay for this privilege because the labor itself is part of the value proposition.

This model appears across industries. YouTube and TikTok provide creation tools; users generate content and build audiences. Modular furniture systems let buyers configure custom solutions. Open-source software gives users the power to modify and extend functionality. Each represents a bet that people will value what they help create more than what they passively receive.

The Future of Ownership and Attachment

As we move toward economies of access over ownership, the IKEA effect suggests strategies for building user attachment. Subscription services struggle with the fact that rented or borrowed items don't trigger ownership psychology. But if those services incorporate meaningful customization or require user effort in setup and maintenance, they can create psychological ownership even without legal title.

The evidence indicates that labor can be sufficient to induce liking and attachment. This means companies can potentially engineer strong user relationships through designed participation, regardless of traditional ownership structures.

The IKEA effect isn't going away. It's wired into how our minds resolve cognitive dissonance and establish psychological ownership. But understanding it changes how we interact with it.

For individuals, awareness provides choice. You can deliberately leverage the effect by taking on projects that will create genuine satisfaction through effort. Build that furniture, cook that complex recipe, customize that software. Knowing the psychology doesn't diminish the real pleasure; it just makes it conscious rather than automatic.

At the same time, recognize when the bias is working against you. When you're clinging to failed projects because of sunk costs, when you're overvaluing your own work and ignoring constructive feedback, when you're paying premiums for the privilege of corporate labor transfer—these are moments to pause and question whether effort justification is clouding your judgment.

For businesses, the effect offers powerful tools for building customer attachment and enabling premium pricing. But with that power comes responsibility. The most sustainable applications will be those that create genuine value for users, not those that simply exploit psychological vulnerabilities.

The companies that thrive will be those that understand a fundamental truth: in an age of abundance and automation, the opportunity to make meaningful effort toward a successful outcome is itself a valuable product. The IKEA effect shows us that humans don't just want finished goods. We want the satisfaction of building something ourselves, the competence boost of successful completion, and the attachment that comes from labor.

That wobbly bookshelf you overpaid for? It's not really about the bookshelf at all. It's about what you proved to yourself when you built it and how that effort transformed your relationship with an otherwise ordinary object. Understanding this doesn't make the feeling any less real. It just helps you decide when to embrace it and when to step back and ask whether you're confusing effort with actual value.

The IKEA effect will continue shaping how we buy, build, and bond with the objects around us. The question isn't whether we're subject to this bias—we are. The question is whether we'll be conscious participants in our own psychology or unwitting subjects of it.

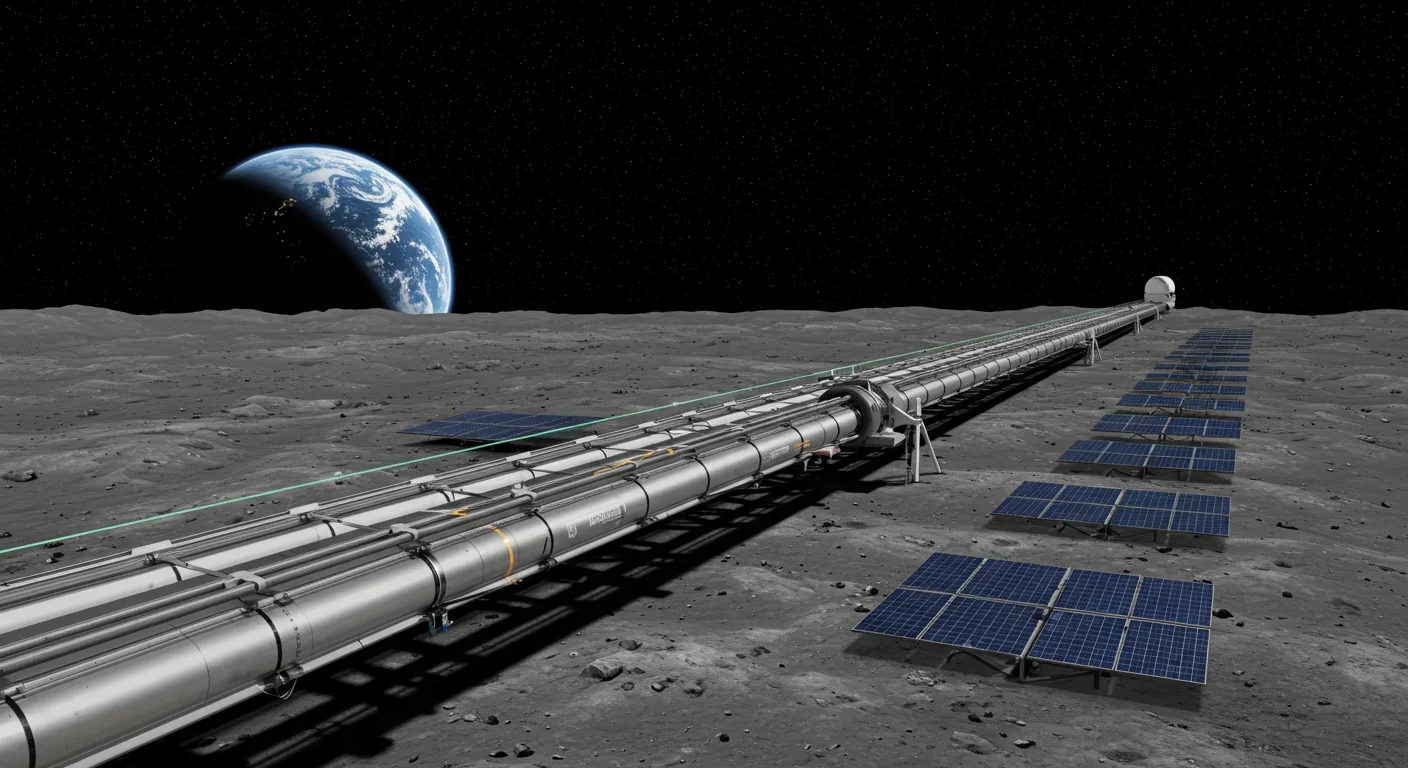

Lunar mass drivers—electromagnetic catapults that launch cargo from the Moon without fuel—could slash space transportation costs from thousands to under $100 per kilogram. This technology would enable affordable space construction, fuel depots, and deep space missions using lunar materials, potentially operational by the 2040s.

Ancient microorganisms called archaea inhabit your gut and perform unique metabolic functions that bacteria cannot, including methane production that enhances nutrient extraction. These primordial partners may influence longevity and offer new therapeutic targets.

CAES stores excess renewable energy by compressing air in underground caverns, then releases it through turbines during peak demand. New advanced adiabatic systems achieve 70%+ efficiency, making this decades-old technology suddenly competitive for long-duration grid storage.

Human children evolved to be raised by multiple caregivers—grandparents, siblings, and community members—not just two parents. Research shows alloparenting reduces parental burnout, improves child development, and is the biological norm across cultures.

Soft corals have weaponized their symbiotic algae to produce potent chemical defenses, creating compounds with revolutionary pharmaceutical potential while reshaping our understanding of marine ecosystems facing climate change.

Generation Z is the first cohort to come of age amid a polycrisis - interconnected global failures spanning climate, economy, democracy, and health. This cascading reality is fundamentally reshaping how young people think, plan their lives, and organize for change.

Zero-trust security eliminates implicit network trust by requiring continuous verification of every access request. Organizations are rapidly adopting this architecture to address cloud computing, remote work, and sophisticated threats that rendered perimeter defenses obsolete.