Underground Air Storage: Renewable Energy's Hidden Battery

TL;DR: Blue carbon bonds are transforming coastal ecosystems into investable assets by linking investor returns to measurable carbon sequestration in mangroves, seagrasses, and salt marshes. These bonds are attracting billions in capital, trading at record prices, and creating financial incentives for conservation.

Within the next decade, you'll likely see mangroves, seagrasses, and salt marshes valued not just as scenic coastlines, but as carbon trading powerhouses that generate measurable returns for investors. A quiet financial revolution is underway where coastal ecosystems are becoming bankable assets, and the instrument driving this shift is the blue carbon bond—a mechanism that's transforming how we fund environmental protection.

Blue carbon bonds work like traditional green bonds but with a twist: the returns directly link to measurable carbon sequestration in coastal ecosystems. Here's the innovation—instead of funding a renewable energy project with predictable outputs, these bonds finance the protection and restoration of living systems that pull carbon from the atmosphere at rates that dwarf terrestrial forests.

Salt marshes bury carbon over 50 times faster than tropical rainforests, sequestering at 210 grams of carbon per square meter annually compared to just 53 grams for tropical forests. Mangroves can store around 1,000 metric tons of carbon per hectare, while seagrasses lock away up to 83,000 metric tons per square kilometer.

Salt marshes bury carbon over 50 times faster than tropical rainforests, sequestering at 210 grams of carbon per square meter annually compared to just 53 grams for tropical forests. Mangroves can store around 1,000 metric tons of carbon per hectare, while seagrasses lock away up to 83,000 metric tons per square kilometer. These ecosystems cover less than 0.5% of the sea bed yet account for more than 50% of all carbon storage in ocean sediments.

The World Bank's outcome bond model offers a concrete example. In Vietnam, a $50 million carbon bond provided upfront funding for a water purification project, with investors receiving payments based on carbon credit sales rather than fixed interest. This structure—linking returns to verified environmental outcomes—is the template being adapted for coastal ecosystem protection.

The numbers tell a compelling story. Blue carbon credits hit $29.30 per metric ton of CO₂ in August 2025, marking a 14.9% rebound from earlier lows. The broader voluntary carbon market attracted $16.3 billion in funding in 2024—an 18-fold increase in total value over credit retirements—and high-quality removal credits are trading between $200 and $1,200 per tonne.

But the real driver? Scarcity combined with regulatory pressure. Blue carbon ecosystems worldwide are disappearing at rates of 2-7% annually, seven times faster than half a century ago. Meanwhile, the UN Environment Programme confirms these habitats capture carbon four times faster than forests, creating a classic supply-demand mismatch that financial markets know how to price.

Corporate buyers are stepping up too. The Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA) could require 135-182 million tons of credits by 2026, and the European Union's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) is placing tariffs on carbon-intensive imports, pushing companies toward offset strategies that include blue carbon.

The Seychelles Blue Bond, launched in 2018, raised $15 million to protect 30% of the nation's ocean territory while restructuring national debt. It's a debt-for-nature swap where financial obligations transform into conservation commitments. Fiji followed with its own green and blue bond, demonstrating that small island nations can access international capital markets by monetizing their coastal assets.

In the Philippines, researchers are co-designing a blue bond framework for marine protected areas in Palawan that integrates fisher livelihoods with mangrove restoration. The project uses discrete choice experiments to understand community trade-offs, ensuring that financial instruments don't bulldoze local needs. This matters because coastal ecosystem services are worth over $25 trillion annually, and indigenous communities often depend on these resources for survival.

"Blue finance instruments—such as blue bonds, debt-for-nature swaps, and parametric insurance—have already demonstrated their potential to address fiscal pressures, enhance climate resilience, and support ecosystem restoration across diverse contexts."

— World Bank, Accelerating Blue Finance Report

Private sector players are entering too. BDO Unibank and Ørsted have issued blue bonds to fund marine conservation projects, while the G20's Blue Halo programme launched in 2022 combines public, philanthropic, and private capital in blended finance structures aligned with UN Sustainable Development Goals.

You can't sell carbon credits without proving the carbon is actually stored, and that's where digital measurement, reporting, and verification (dMRV) tools change the game. Remote sensing technologies like satellite imagery and LiDAR are already used in forestry carbon projects to estimate sequestration potential, and they're being adapted for coastal environments.

Digital MRV enhances traditional processes through remote sensing, data analytics, and blockchain, providing real-time transparency that reduces human error and speeds up credit issuance. Think of it like the difference between manual bookkeeping and digital accounting—the former is slow and prone to mistakes, the latter is instant and auditable.

Blockchain-based carbon credit tracking creates immutable records that reduce fraud and double counting risks. AI-driven satellite imagery and machine learning algorithms enable precise monitoring of carbon sequestration in wetlands and coastal vegetation. These digital tools are essential because investors demand robust verification before committing capital—and 50% of all retired carbon credits in 2024 met high-quality standards, up from 29% in 2021.

Land tenure issues are a major roadblock. Who owns the mangrove forest—the state, the community, or private landholders? Regulatory uncertainty and long verification timelines create supply bottlenecks that prevent projects from scaling. In many coastal regions, property rights are murky, making it difficult to establish who can legally sell carbon credits generated by ecosystem restoration.

Nitrogen pollution threatens the permanence of carbon stored in salt marshes by stimulating microbial decomposition of organic matter. When nitrate is abundant, microbial communities shift toward carbon release rather than sequestration, potentially undermining the environmental credibility of blue carbon projects. This means monitoring must extend beyond simple carbon accounting to include water quality and microbial dynamics.

Only 9% of total nature-based finance currently goes to marine environments, highlighting a massive funding gap despite the ocean's carbon sequestration capacity.

Only 9% of total nature-based finance currently goes to marine environments, highlighting a massive funding gap despite the ocean's carbon sequestration capacity. The lack of universal standards for credit validation leads to market fragmentation and inconsistencies, and high project implementation and verification costs create barriers for smaller organizations trying to enter the market.

The Sustainable Blue Economy Finance Principles, launched in 2018, provide a global framework covering 14 characteristics that include protection of marine ecosystems, transparency, and science-led approaches. These principles legitimize blue finance projects as sustainable investments and help standardize what qualifies as a credible blue carbon bond.

Article 6 of the Paris Agreement could create opportunities for trading blue carbon credits internationally, allowing countries to cooperate on emissions reductions. Governments in Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America have launched programs to boost coastal ecosystem investment, recognizing that protecting mangroves and seagrasses delivers climate mitigation, coastal protection, and fisheries support simultaneously.

The Core Carbon Principles from the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market are improving market transparency by establishing what constitutes a high-quality carbon credit. This standardization helps investors distinguish legitimate projects from greenwashing, building confidence that fuels capital deployment.

Development institutions and multilateral banks are providing technical assistance, concessional capital, and de-risking mechanisms to mobilize private capital at scale. These blended finance platforms combine public, philanthropic, and private funding to share risks and align incentives—critical for early-stage markets where risk perception remains high.

Beyond carbon accounting, blue carbon projects deliver tangible local benefits. Mangrove restoration improves food security and fisher livelihoods while protecting coastlines from storm surges. Seagrass beds support biodiversity and nursery habitats for commercial fish species. Salt marshes filter nutrients and pollutants from runoff, improving water quality for adjacent communities.

The challenge is ensuring these co-benefits reach the people who've stewarded these ecosystems for generations. Debt-for-mangrove swaps are being designed to generate financial flows that directly support local fisher livelihoods rather than simply paying off national debt. Discrete choice experiments help communities articulate trade-offs between marine protected area restrictions and economic opportunities, ensuring that conservation doesn't become another form of dispossession.

Health co-benefits from mangrove conservation—improved nutrition, reduced pollution exposure—create cross-sectoral incentives that can attract funding beyond climate finance. When blue carbon bonds account for these multiple benefits, they become more attractive to impact investors seeking both environmental and social returns.

Green bonds fund renewable energy, energy efficiency, and clean transportation—projects with predictable engineering outputs. Blue carbon bonds finance living ecosystems with inherent complexity and variability. A solar panel's energy output is calculable; a mangrove forest's carbon sequestration depends on water chemistry, tidal patterns, and microbial communities.

This biological complexity introduces permanence risk that doesn't exist with traditional green infrastructure. A wind turbine won't spontaneously decompose; a salt marsh exposed to nitrogen pollution can shift from carbon sink to carbon source. That's why blue carbon bonds require more sophisticated monitoring and adaptive management compared to their green counterparts.

But the advantage is scale. Green bonds raised hundreds of billions for renewable energy over the past decade, proving that investors will fund environmental projects at scale when frameworks exist. Blue carbon bonds can tap this established market infrastructure while offering differentiation through higher sequestration rates and ecosystem co-benefits.

Third-party verification and reporting frameworks are essential for both green and blue bonds to mitigate greenwashing and maintain investor trust. The difference is that blue carbon verification requires ecological expertise—understanding sediment dynamics, nutrient cycling, and ecosystem resilience—not just engineering assessments.

From a pure financial perspective, blue carbon bonds offer several attractions. Principal protection structures like the World Bank's outcome bonds shield investors from downside risk while linking upside potential to carbon credit sales. This asymmetric payoff appeals to institutional investors who need capital preservation but want exposure to environmental markets.

Record-high blue carbon credit prices signal growing demand from corporate buyers facing net-zero commitments. High-quality removal credits command premium prices—$11-15 per tonne for forward contracts versus $3-6 for spot prices—indicating that long-term carbon storage projects generate better returns than avoidance-only strategies.

"Blue carbon credits come from activities like restoring mangroves, protecting seagrass, and conserving salt marshes. These ecosystems provide key benefits including preserving biodiversity, boosting coastal resilience, and helping local communities."

— Carbon Credits Market Analysis

But risks exist. Ecosystem loss rates of 2-7% annually mean that protection alone isn't enough—active restoration is often required, increasing project costs. Long verification timelines and regulatory uncertainty can delay credit issuance, creating cash flow timing mismatches. Price volatility in carbon markets—where benchmarks hit 15-month highs then drop to five-month lows within weeks—introduces market risk that must be managed.

Blended finance platforms and de-risking mechanisms from development institutions can mitigate some of these risks by providing concessional capital that absorbs early-stage uncertainty. This allows private investors to enter with lower risk premiums, improving project economics.

Embedding blue finance into national development plans, budgets, and regulatory systems is the critical first step for mainstreaming the market. Currently, blue carbon projects are often one-off experiments rather than systematic approaches. Governments need to integrate coastal ecosystem protection into climate strategies with the same priority given to renewable energy.

Linking payoff to a pool or basket of projects can reduce customization costs and allow issuers to raise capital at scale. Instead of structuring individual bonds for each mangrove restoration site, aggregating multiple projects under a single instrument spreads fixed costs and creates investable scale that attracts larger institutional investors.

Digital MRV tools that provide real-time, transparent data are essential infrastructure for scaling. When satellite monitoring and blockchain tracking become standard rather than experimental, the cost per project drops dramatically and verification timelines compress from years to months.

Solving land tenure issues requires political will and legal reform. Many coastal regions lack clear property rights frameworks, making it impossible to establish who can legally monetize ecosystem services. Countries that clarify these rights—whether recognizing community ownership, establishing state custodianship, or creating hybrid models—will attract more blue carbon investment.

Southeast Asia holds vast mangrove resources but also faces rapid coastal development pressure. Countries like Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam are launching restoration programs that could generate millions of carbon credits annually. The question is whether they compete for limited buyer demand or cooperate to establish regional standards that boost overall market credibility.

Africa's coastline remains underutilized in blue carbon markets despite significant ecosystem potential. Small island developing states face existential threats from sea-level rise, making coastal ecosystem protection both a climate mitigation and adaptation strategy. Latin American countries with extensive mangrove forests in Brazil, Mexico, and Ecuador could become major blue carbon credit exporters.

The challenge is ensuring this doesn't become another extractive relationship where Global South countries provide ecosystem services while Global North investors capture financial returns. Co-designed investment structures that integrate local livelihoods and community participation are essential for equitable outcomes.

International frameworks like Article 6 of the Paris Agreement could facilitate bilateral trading where developed nations invest in coastal restoration abroad and count credits toward their national commitments. This creates direct incentives for cross-border capital flows but requires robust accounting to prevent double-counting and ensure environmental integrity.

While coastal blue carbon dominates current discussions, deep blue carbon—storing CO₂ in the deep ocean—could dwarf coastal ecosystem capacity. Denmark's "Greensand" project aims to sequester up to 8 million tonnes of CO₂ annually by 2030 in North Sea sediments, potentially 10-20 times the scale of coastal projects.

This shifts the conversation from ecosystem restoration to geological storage in marine environments. If deep blue carbon proves viable and monetizable through similar bond structures, it could attract orders of magnitude more capital than coastal projects. But the ecological risks are largely unknown—what happens to deep ocean ecosystems when you inject millions of tons of CO₂? Who owns the seabed rights to profit from this activity?

These questions need answers before deep blue carbon bonds become mainstream, but the potential is enormous. The deep ocean stores 90% of all ocean carbon, and if even a small fraction of that capacity can be harnessed safely, it changes the calculus for climate finance entirely.

Due diligence for blue carbon bonds requires ecological expertise, not just financial analysis. Investors need to understand sediment accretion rates, tidal hydrology, and nutrient pollution impacts—areas where traditional bond analysts have no experience. This knowledge gap creates opportunities for specialized advisory firms and ESG consultants who can translate ecosystem science into investment risk metrics.

Permanence guarantees are harder to structure for living systems than for infrastructure. A mangrove forest could be destroyed by a typhoon, a seagrass meadow could succumb to disease, or a salt marsh could be overwhelmed by sea-level rise.

Permanence guarantees are harder to structure for living systems than for infrastructure. A mangrove forest could be destroyed by a typhoon, a seagrass meadow could succumb to disease, or a salt marsh could be overwhelmed by sea-level rise. Insurance products and reserve buffer pools—where a percentage of credits are held back to cover reversals—can mitigate but not eliminate these risks.

Verification costs for blue carbon projects remain high compared to simpler renewable energy projects. On-site monitoring, sediment core sampling, and ecological surveys require specialized labor and equipment. As dMRV tools mature and costs decline, this barrier will diminish, but early-stage projects face significant upfront verification expenses that affect returns.

Liquidity in secondary markets for blue carbon credits is still developing. While prices hit record highs in 2025, trading volumes remain small compared to renewable energy credits. Investors need to plan for potentially holding positions to maturity rather than assuming easy exit opportunities.

If blue carbon bonds scale as projected, we'll need thousands of professionals who understand both marine ecology and structured finance. Currently, marine biologists rarely study bond markets, and investment bankers rarely understand sediment biogeochemistry. Universities and training programs are just beginning to bridge this gap with interdisciplinary programs in blue economy finance.

Local communities need capacity building too. Stewarding a marine protected area that generates carbon credits requires understanding monitoring protocols, compliance requirements, and financial reporting—skills that fishing communities may not possess. Equitable blue carbon projects must invest in local technical capacity, not just ecosystem restoration.

Regulators face their own learning curve. Governments must develop frameworks for carbon accounting, credit issuance, and market oversight specific to marine environments. Copy-pasting terrestrial forestry rules won't work because coastal ecosystems operate under different ecological dynamics.

Blue carbon bonds represent a genuine innovation in climate finance—not just a rebranding of existing instruments. By linking financial returns to measurable ecosystem outcomes, they create direct economic incentives for coastal conservation that traditional philanthropy and government funding alone cannot achieve.

The market is still young, with total blue carbon bond issuance in the hundreds of millions rather than billions. But the $16 billion flowing into voluntary carbon markets in 2024 demonstrates investor appetite for environmental assets, and record-high prices for blue carbon credits signal that coastal ecosystems are being repriced by the market.

Whether this financial mechanism can scale fast enough to counter the 2-7% annual loss rate of blue carbon ecosystems remains uncertain. But the combination of robust digital monitoring, clear policy frameworks, and growing investor demand suggests that the infrastructure for large-scale blue carbon finance is emerging.

The critical variable is political will. Governments must integrate blue finance into national strategies, clarify property rights, and invest in monitoring infrastructure. Without that foundation, blue carbon bonds will remain niche instruments rather than transformative tools for coastal protection.

For communities living along the world's coastlines, the promise is compelling: their mangroves, seagrasses, and salt marshes could become valuable assets that generate income while protecting against storms and supporting fisheries. But only if the financial structures ensure that value flows back to those who've protected these ecosystems for generations, not just to distant investors calculating returns on blue carbon bonds.

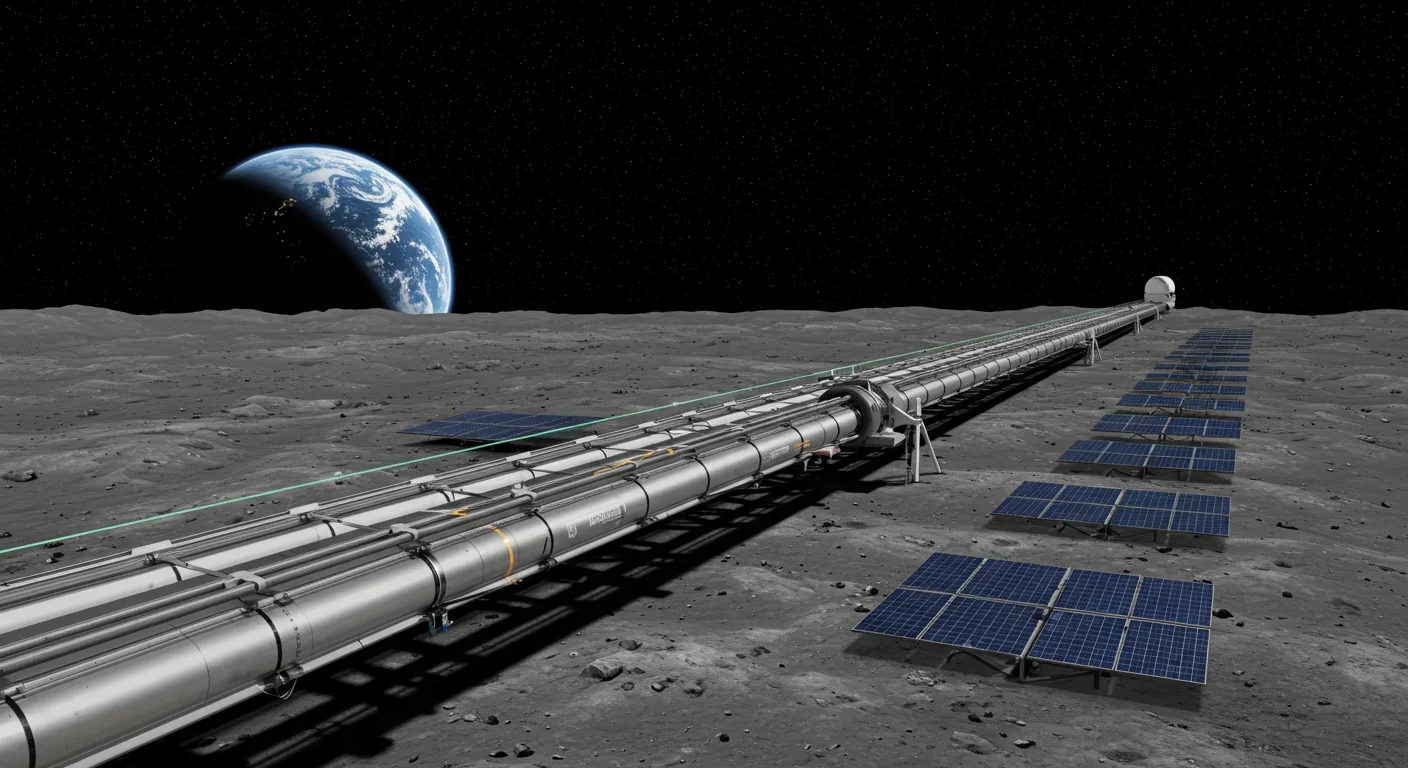

Lunar mass drivers—electromagnetic catapults that launch cargo from the Moon without fuel—could slash space transportation costs from thousands to under $100 per kilogram. This technology would enable affordable space construction, fuel depots, and deep space missions using lunar materials, potentially operational by the 2040s.

Ancient microorganisms called archaea inhabit your gut and perform unique metabolic functions that bacteria cannot, including methane production that enhances nutrient extraction. These primordial partners may influence longevity and offer new therapeutic targets.

CAES stores excess renewable energy by compressing air in underground caverns, then releases it through turbines during peak demand. New advanced adiabatic systems achieve 70%+ efficiency, making this decades-old technology suddenly competitive for long-duration grid storage.

Human children evolved to be raised by multiple caregivers—grandparents, siblings, and community members—not just two parents. Research shows alloparenting reduces parental burnout, improves child development, and is the biological norm across cultures.

Soft corals have weaponized their symbiotic algae to produce potent chemical defenses, creating compounds with revolutionary pharmaceutical potential while reshaping our understanding of marine ecosystems facing climate change.

Generation Z is the first cohort to come of age amid a polycrisis - interconnected global failures spanning climate, economy, democracy, and health. This cascading reality is fundamentally reshaping how young people think, plan their lives, and organize for change.

Zero-trust security eliminates implicit network trust by requiring continuous verification of every access request. Organizations are rapidly adopting this architecture to address cloud computing, remote work, and sophisticated threats that rendered perimeter defenses obsolete.