Intercropping Boosts Farm Yields 20-50% While Building Resilience

TL;DR: Coastal communities are creating migration corridors to let salt marshes move inland as seas rise, balancing the economic benefits of natural flood protection against property rights and development pressures in a strategy that's cheaper and more adaptive than building ever-higher seawalls.

Along the Massachusetts coast, engineers are recalculating seawalls. In Southwest Florida, planners are redrawing maps. In Chesapeake Bay communities, property owners are weighing offers to sell land they thought would stay dry for generations. They're not preparing for disaster—they're preparing for migration. Salt marsh migration.

It's a simple truth that's reshaping coastal conservation: when seas rise, marshes move or they die. For thousands of years, these grassy wetlands have crept inland as oceans expanded, maintaining their position at the land-sea boundary. But now, human development blocks their retreat, creating what scientists call coastal squeeze. The marsh has nowhere to go, and drowning becomes inevitable.

What's emerging across American coastlines is a conservation strategy that requires communities to do something uncomfortable: give up land. Not to development, not to parks, but to wetlands that will someday need it. These migration corridors represent a fundamental shift in how we think about coastal protection—from fighting nature to accommodating it.

Salt marshes aren't static landscapes. They're dynamic ecosystems that respond to water levels by shifting their position, sometimes over decades, sometimes within a single lifetime. Research from the Great Sippewissett Marsh in Massachusetts tracked this process for 50 years and arrived at a sobering conclusion: more than 90% of the world's salt marshes will be underwater by 2100 unless they can migrate inland.

The mechanics of marsh migration are surprisingly straightforward. As seas rise, low marsh species that tolerate frequent flooding begin appearing where high marsh species once dominated. Over time, the entire plant community shifts upslope, colonizing what was previously dry land. Chesapeake Bay's water levels have risen 30 centimeters over the last century, and scientists project another 40 to 130 centimeters by 2100. That's enough to push marshes hundreds of meters inland—if they have somewhere to go.

But increasingly, they don't. Between rising waters and the hard edge of development—seawalls, roads, buildings, subdivisions—marshes are running out of room. This coastal squeeze is most severe in heavily developed areas where every meter of shoreline has been claimed for human use.

More than 90% of the world's salt marshes will be underwater by 2100 unless they can migrate inland as seas rise.

The ecological value of salt marshes has been cataloged exhaustively: they're nurseries for commercial fish, stopover sites for migratory birds, filters for pollutants, and some of the most productive ecosystems on the planet. But it's their economic value that's finally getting attention from people who control budgets.

A study from MIT calculated that a healthy salt marsh in front of a seawall can reduce the required wall height by 1.7 meters—about 5.5 feet. That translates to massive construction savings. Instead of building a 4-meter seawall, you can build a 2.3-meter wall fronted by marsh and get the same storm protection. The marsh absorbs wave energy through its dense vegetation, dramatically reducing the force that reaches the wall.

"Protecting coastal marshes is not just something that would be nice to do, but it's actually economically justifiable."

— Heidi Nepf, MIT Professor

Heidi Nepf, an MIT professor who led the research, explained that her team developed a free wave-attenuation model that coastal engineers can use to calculate marsh value for specific sites. The model revealed something surprising: you don't need vast expanses of marsh to see benefits. "A relatively short marsh, tens of meters wide, can give a good protection effect," Nepf noted.

This overturns decades of thinking that treated marshes as nice-to-have ecological features rather than critical infrastructure. A comprehensive review of over 20,000 scientific articles found that 71% concluded nature-based solutions are cost-effective for mitigating floods, hurricanes, and storm surge. When you compare the cost of maintaining a living marsh to the expense of replacing aging seawalls every few decades, the economics shift dramatically.

Salt marshes also provide storm protection that gray infrastructure can't match: flexibility. Seawalls reduce impacts in the short term but create lock-ins that increase exposure to climate risks long term, according to a recent IPCC report. They're inflexible, expensive to modify, and offer no ecological benefits. When they fail, the damage is catastrophic because communities have built right up to their edge, assuming permanent protection.

Marshes, by contrast, adapt. They accrete sediment, rebuild after storms, and if given space, migrate to maintain their protective function even as sea levels rise. That's the vision driving migration corridor planning.

The concept sounds simple: identify low-lying land adjacent to existing marshes and keep it undeveloped so wetlands can expand into it. The reality involves complex negotiations, competing interests, and communities confronting uncomfortable questions about what land is expendable.

Southwest Florida's vulnerability assessment, conducted by the Charlotte Harbor National Estuary Program with EPA funding, mapped current marsh extent and projected where marshes would need to move over the next 80 years. The study identified locations where "the current pace of sea-level rise appears to allow some locations for marsh migration on mainland shores," while also finding areas where marshes are already drowning with no place to go. Those maps now guide local planning decisions about which parcels to prioritize for conservation.

In Massachusetts, communities around Salem and Juniper Cove are experimenting with hybrid approaches: maintaining existing seawalls while restoring marshes in front of them. Benefit-cost analyses show ratios greater than one for these marsh-fronted walls, meaning the economic benefits exceed the costs. As marshes naturally migrate upslope over coming decades, the plan is to allow them space to retreat behind the current seawall location, eventually replacing the hard structure with living shoreline.

The Chesapeake Bay offers perhaps the most advanced examples of migration planning in rural areas. Studies of three low-lying communities in Dorchester, Wicomico, and Somerset counties revealed both the potential and the tensions. Researchers found that "the future of many coastal wetlands will depend greatly on their capacities to migrate into uplands," but they also documented that migration affects people's property, livelihoods, and cultural heritage.

These communities are using workshops and participatory planning to identify which lands might serve as migration zones. Some property owners are open to conservation easements that allow their land to gradually convert to wetland. Others are candidates for buyouts. The process requires negotiating not just with individual owners but with entire communities whose identity is tied to their landscape.

Creating migration corridors requires more than goodwill—it requires legal frameworks that balance public interest in coastal resilience with private property rights. Several policy mechanisms are emerging as particularly useful.

Rolling easements are agreements that allow public access or ecological use to shift landward as shorelines erode or seas rise. Unlike traditional easements that fix boundaries in place, rolling easements acknowledge that coastal features move. Texas's Supreme Court ruled that public easements don't automatically roll with sudden shoreline changes caused by storms, protecting property owners from having public beach rights suddenly appear on their land. But planned rolling easements, established through agreements before crisis hits, can create legal pathways for marshes to migrate without endless litigation.

Creating migration corridors means balancing coastal resilience with private property rights through innovative legal frameworks like rolling easements and strategic land acquisition.

Strategic land acquisition is more straightforward but more expensive. Federal and state agencies, along with land trusts, purchase properties in projected migration zones and either leave them undeveloped or convert them to compatible uses like agriculture or low-intensity recreation. When seas rise, these lands naturally convert to marsh without conflict. California's Coastal Act provides a regulatory model where coastal development permits must preserve or enhance public access, creating a framework that could be adapted to preserve migration corridors.

Zoning changes and development restrictions represent the most politically challenging approach. Some jurisdictions are creating overlay districts that prohibit or severely limit development in areas identified as future marsh habitat. Almost 74% of salt marsh habitat in Charlotte Harbor Estuary is protected, yet habitat continues to be lost to development, demonstrating that protection alone isn't enough without proactive corridor planning.

Federal guidance from the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs now supports valuing ecosystem services in project planning, providing bureaucratic backing for marsh-based flood protection strategies. This policy shift means agencies like FEMA can use benefit-cost analysis toolkits that recognize marsh value, potentially steering federal disaster mitigation funding toward natural solutions.

Property rights make migration corridor planning in the United States fundamentally different from ecological planning. You can't simply designate land as "future wetland" and walk away. Someone owns that land, and they have legally protected rights to develop it.

This creates profound equity questions. Environmental science professor Mark Lubell notes that "seawalls are expensive. Poor communities with people of color have a harder time affording them, and poor communities in the Bay Area are more vulnerable to sea level rise." If wealthy neighborhoods can afford seawalls that block marsh migration while poor communities must accept wetland expansion, migration corridors could become another form of environmental injustice.

Research in Chesapeake Bay communities highlights "human-ecological misalignments that emerge with marsh migration," leading to concerns about equity and justice. Rural landowners who lack resources to relocate or adapt may bear disproportionate costs of migration strategies designed to protect more valuable properties elsewhere on the coast.

"The right to exclude others from one's property is one of the most important rights of property owners, and the state may only take it away through eminent domain with just compensation."

— Texas Supreme Court

The challenge extends beyond fairness to fundamental questions about who decides. Does a state have the right to prevent development on private land to preserve future marsh habitat? The Texas Supreme Court emphasized that "the right to exclude others from one's property is one of the most important rights of property owners, and the state may only take it away through eminent domain with just compensation." That legal principle requires government to either pay market value for migration corridor land or persuade owners to participate voluntarily.

Buyout programs address this directly by purchasing properties at fair market value, but they're expensive and slow. After major storms, FEMA offers buyouts to repeatedly flooded properties, but the program is reactive rather than proactive. Applying buyouts to create migration corridors before flooding occurs requires upfront funding that many jurisdictions lack.

Some creative approaches are emerging. Instead of purchasing land outright, some programs buy development rights, allowing landowners to continue using property for agriculture or recreation while preventing construction. Others establish "land banks" where purchased properties are leased back to farmers until sea-level rise makes them unsuitable for crops, at which point they convert to marsh. These hybrid models reduce upfront costs while achieving long-term conservation goals.

The difference between successful migration corridors and failing ones will become starkly visible over the next few decades. In places that plan ahead, marshes will shift gradually inland, maintaining their protective function and ecological services throughout the transition. Coastal communities will experience fewer flood losses, lower storm damage costs, and sustained fisheries.

In places that fail to plan, marshes will drown in place, leaving coastlines exposed to waves that previously dissipated through vegetation. Studies predict that wetland loss increases risks that sea-level rise and storm surge pose to coastal infrastructure. Communities will spend billions on ever-higher seawalls that lock them into rigid defensive positions, cutting off their connection to the ecosystems that once protected them.

The technology to support migration planning is improving rapidly. MIT researchers are developing drone imaging and machine-learning methods to rapidly create detailed marsh maps, reducing the labor intensity of field data collection. These tools will let planners evaluate marsh protective value and identify optimal migration pathways more quickly and accurately than traditional methods.

The EPA has released tools specifically designed for this challenge, including a "Being Prepared for Climate Change Workbook" and "Synthesis of Adaptation Options for Coastal Areas" that help communities develop risk-based plans. NOAA's focus on nature-based solutions brings federal expertise and potential funding to support local initiatives.

There's an element of migration corridor planning that rarely appears in cost-benefit analyses but haunts the discussions nonetheless: we're talking about ecosystems as if they're infrastructure, calculating their flood-protection value and carbon-sequestration capacity while skirting around the deeper question of whether we have any obligation to preserve them beyond their utility to us.

Salt marshes support species that exist nowhere else—specialized plants adapted to twice-daily saltwater inundation, fish that require estuarine nurseries, birds that depend on coastal wetlands during migration. When marshes drown because we've boxed them in with development, these species don't get to vote on alternative habitats. They simply disappear.

The migration corridor approach at least acknowledges that these ecosystems have a right to persist, even if that persistence requires sacrifice from human landowners. It's a different ethical framework than "use it until it's gone," and it requires a longer time horizon than most political and economic systems naturally operate on.

Whether it prevails may depend less on scientific consensus about marsh value than on whether coastal communities can imagine futures where they share space with dynamic landscapes that shift and change. The alternative—fortifying every meter of coastline with concrete and steel—is both more expensive and more fragile, but it offers the illusion of control.

The migration corridor movement is spreading beyond individual projects to influence regional planning. Comprehensive reviews show that nature-based solutions consistently prove cost-effective across a range of hazards, building momentum for approaches that work with natural processes rather than against them.

But implementation faces headwinds. Nature-based solutions require more space and more time to establish than hard infrastructure. Private investment remains limited because financing models that rely on debt don't capture the public-good benefits that marshes provide. A seawall protects specific properties whose owners can be charged for the protection. A marsh protects entire coastal areas, filters water for everyone downstream, supports regional fisheries, and sequesters carbon that benefits the global atmosphere. Capturing that diffuse value in a funding model is difficult.

The solution emerging in some regions is hybrid governance—partnerships between federal agencies, state programs, local governments, and land trusts that pool resources and coordinate planning across jurisdictions. The Southwest Florida assessment exemplifies this approach, combining EPA funding with regional planning and local implementation.

Climate projections suggest that wherever migration corridors are created, they'll be used. Sea-level rise is accelerating, and coastal storms are intensifying. The marshes will need somewhere to go, and communities face a choice: plan proactively for that migration while options remain, or respond reactively after marshes have drowned and coastal protection has failed.

Creating migration corridors means playing a long game in a political culture that favors short-term wins. The land purchased or protected today may not visibly become marsh for 20 or 30 years. Elected officials who champion these programs may be out of office before the benefits materialize. Property owners who accept easements are making sacrifices for ecological futures they may not live to see.

Yet the alternative—letting marshes drown because we couldn't imagine giving up a strip of land nobody was using anyway—will look increasingly indefensible as flood damages mount and seawall costs spiral. IPCC scientists explicitly warn that seawalls create long-term lock-ins that limit future adaptation options. Every meter of coast we harden is a meter where marsh migration becomes impossible.

The communities taking action now are betting that flexible, adaptive strategies will outperform rigid defensive ones. They're accepting that coastlines are dynamic features, not permanent boundaries, and that human uses must accommodate natural processes rather than suppress them. They're discovering, as studies consistently show, that marshes fronting seawalls provide better protection at lower cost than taller walls alone.

The question facing every coastal community is whether they'll make room for retreat before retreat becomes unavoidable. Because the marshes are moving, one way or another. They'll either migrate inland through corridors we've prepared, or they'll drown against barriers we've erected. The first scenario gives us a chance to maintain the coastal protection and ecological services these ecosystems provide. The second guarantees we'll lose both.

Seas don't negotiate. Marshes don't wait for political consensus. They're already responding to the water levels we've created. Whether human communities can respond with equal adaptability may determine which coastlines remain habitable—and which become just another place the ocean took back.

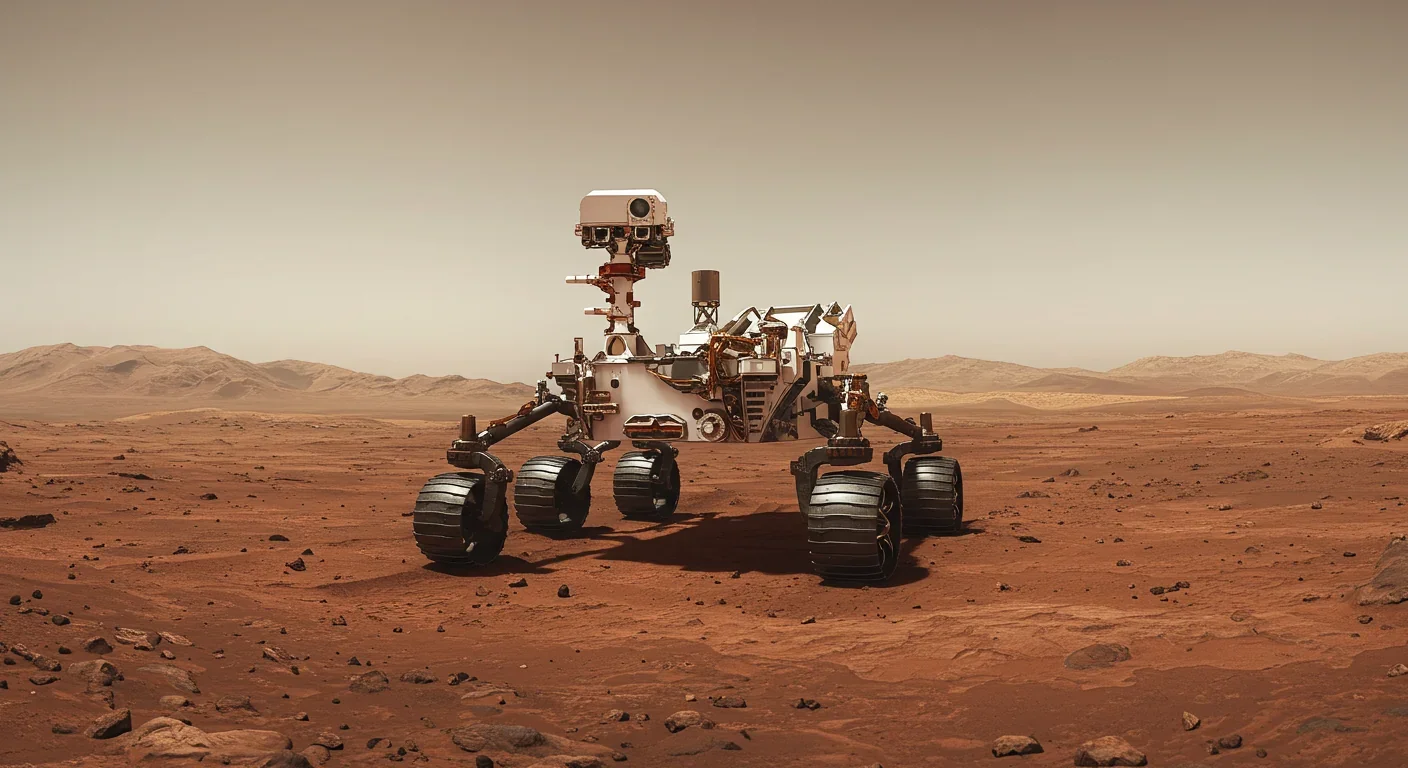

Curiosity rover detects mysterious methane spikes on Mars that vanish within hours, defying atmospheric models. Scientists debate whether the source is hidden microbial life or geological processes, while new research reveals UV-activated dust rapidly destroys the gas.

CMA is a selective cellular cleanup system that targets damaged proteins for degradation. As we age, CMA declines—leading to toxic protein accumulation and neurodegeneration. Scientists are developing therapies to restore CMA function and potentially prevent brain diseases.

Intercropping boosts farm yields by 20-50% by growing multiple crops together, using complementary resource use, nitrogen fixation, and pest suppression to build resilience against climate shocks while reducing costs.

The Baader-Meinhof phenomenon explains why newly learned information suddenly seems everywhere. This frequency illusion results from selective attention and confirmation bias—adaptive evolutionary mechanisms now amplified by social media algorithms.

Plants and soil microbes form powerful partnerships that can clean contaminated soil at a fraction of traditional costs. These phytoremediation networks use biological processes to extract, degrade, or stabilize toxic pollutants, offering a sustainable alternative to excavation for brownfields and agricultural land.

Renters pay mortgage-equivalent amounts but build zero wealth, creating a 40x wealth gap with homeowners. Institutional investors have transformed housing into a wealth extraction mechanism where working families transfer $720,000+ over 30 years while property owners accumulate equity and generational wealth.

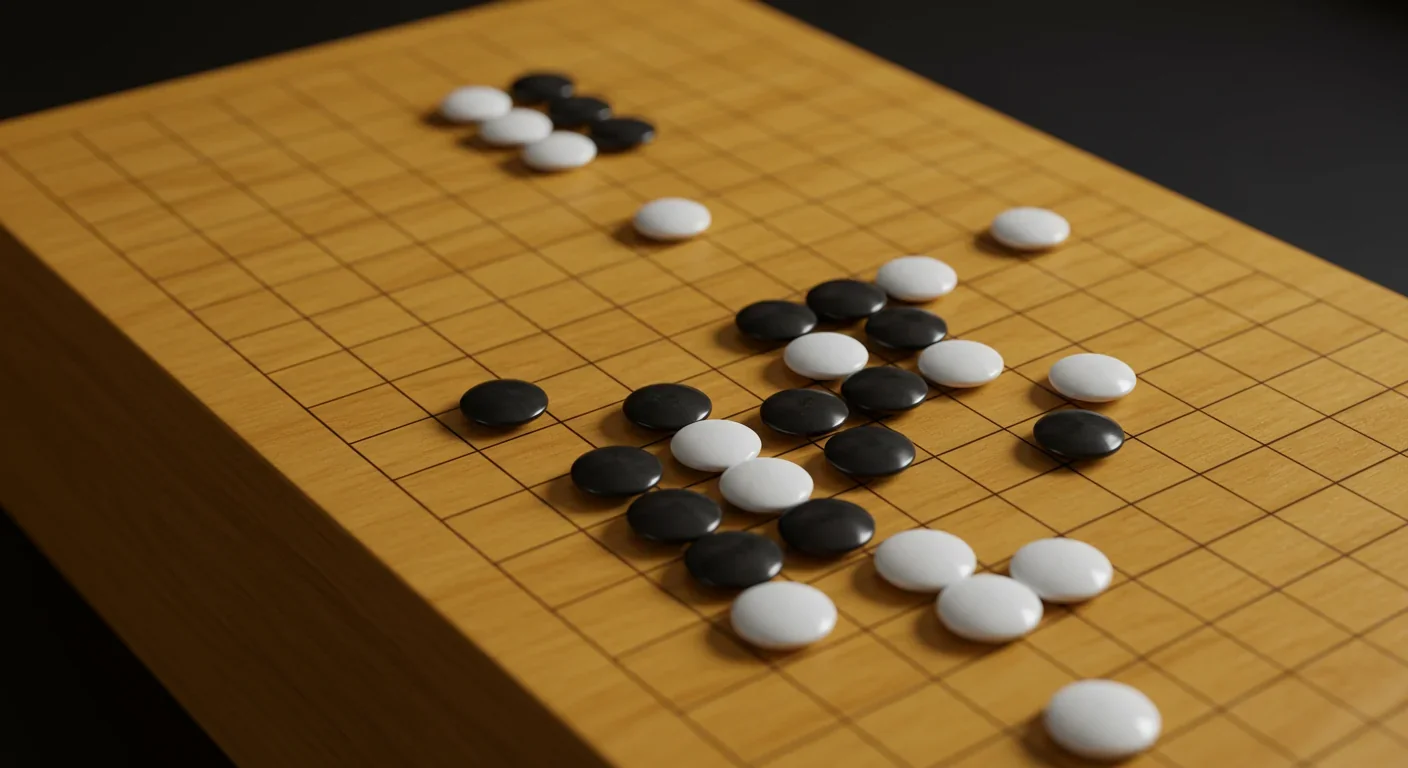

AlphaGo revolutionized AI by defeating world champion Lee Sedol through reinforcement learning and neural networks. Its successor, AlphaGo Zero, learned purely through self-play, discovering strategies superior to millennia of human knowledge—opening new frontiers in AI applications across healthcare, robotics, and optimization.