When Reality Becomes Partisan: The Death of Shared Truth

TL;DR: Despite unprecedented material abundance, people in prosperous societies increasingly report purposelessness and disconnection. This 'meaning crisis' stems from hedonic adaptation, choice overload, social isolation, and eroded meaning-making traditions—but emerging solutions in contemplative practices, intentional communities, and reimagined work offer pathways forward.

In 2024, researchers identified something startling in prosperous nations: 89% of young adults aged 16-29 in the UK reported their lives had no meaning. Not struggling for survival. Not lacking opportunities. Simply feeling nothing matters. Welcome to what cognitive scientist John Vervaeke calls the "meaning crisis"—and it's spreading faster than any economic downturn.

You've probably felt it yourself. That creeping sense that despite having more stuff, more choices, and more comfort than any generation in history, something fundamental is missing. The paradox isn't subtle: we've built societies that deliver unprecedented material abundance while leaving people emotionally starving.

Here's what doesn't make sense at first glance. Countries with the highest GDP per capita often report declining life satisfaction. Americans have twice the purchasing power their grandparents had, yet depression rates have reached historic highs, affecting nearly 30% of adults in recent surveys. Among adolescents and young adults globally, the burden of depression increased by 49% between 1990 and 2021.

The World Health Organization now classifies depression as a leading cause of disability worldwide, affecting over 280 million people. Loneliness has become so pervasive the WHO declared it a global public health concern, with research showing weak social connections increase mortality risk as much as smoking 15 cigarettes daily.

What's happening? Why does getting what we want leave us wanting?

The answer starts with something psychologists call the hedonic treadmill. Your brain is prediction machinery, constantly adjusting its baseline for normal. That new car delivers a dopamine rush for about three months, then becomes invisible background. The promotion feels amazing until it becomes your new baseline, and suddenly you're eyeing the next level up.

This isn't a character flaw. It's hedonic adaptation, a fundamental feature of human neuroscience. Brickman and Campbell's landmark 1971 study found that lottery winners returned to their baseline happiness levels within months. Same with accident victims who became paraplegics. Our brains are wired to adapt.

Your brain builds models of what to expect, then updates them based on experience. As you acquire more, expectations rise in tandem—the gap between reality and expectation remains constant, no matter how much you gain.

The mechanism involves predictive processing—your brain builds models of what to expect, then updates them based on experience. As you acquire more, expectations rise in tandem. No matter how much you gain, the gap between reality and expectation remains constant. According to research on hedonic adaptation, making more money increases expectations and desires by exactly the same amount, resulting in zero permanent happiness gain.

But adaptation is only part of the puzzle.

Barry Schwartz identified another culprit: the paradox of choice. When your grandmother went shopping for jeans, she had maybe three options. You have thousands. Should feel liberating, right?

Instead, research shows choice overload leads to decision paralysis and decreased satisfaction. With infinite options, you can always imagine a better choice you didn't make. Every decision becomes an opportunity for regret. The psychological weight of maximizing—trying to make the absolute best choice—creates chronic low-grade anxiety.

Schwartz's research revealed that maximizers reported significantly less life satisfaction, more regret, and more depression than satisficers (people who accept "good enough"). The abundance of choice modern life promises as freedom actually constrains our capacity for contentment.

Now layer in sociologist Robert Putnam's Bowling Alone thesis. Americans bowl more than ever, but league membership has collapsed by 60% since the 1960s. That's not really about bowling—it's a metaphor for the unraveling of social fabric. Community organizations, civic groups, dinner parties, and neighborhood gatherings have all declined precipitously.

Putnam documented how social capital—the networks and norms that enable collective action—has eroded across every demographic. We're more isolated despite being more "connected" than ever. Research from Oregon State University found that loneliness correlates directly with the amount and frequency of social media use, suggesting digital connection may actually deepen isolation.

"The crises that our world is facing seem to be constantly growing, leading to enormous and devastating systemic effects across the globe. Yet, the ripples of the human predicament are also reaching our personal lives in unexpected ways—through chronic loneliness, loss of coherence to reality, and a widespread feeling of insignificance."

— John Vervaeke, cognitive scientist

Recent studies from Harvard and other institutions reveal that loneliness isn't just emotional suffering—it's physiologically destructive. The pandemic exposed deep structural loneliness that was already present, accelerating what researchers call "deaths of despair."

Robert Putnam explains that we're not just lonely individually—we've lost the institutions that once wove us together. Churches, unions, clubs, and fraternal organizations provided not just social contact but meaningful social roles. They answered the question: "What am I for?"

That brings us to perhaps the deepest layer: the erosion of shared meaning-making frameworks. For most of human history, religious and cultural traditions provided ready-made answers to life's biggest questions. Not necessarily correct answers, but coherent frameworks that linked individual existence to cosmic significance.

Secularization has liberated us from dogma but also stripped away these scaffolds. About 35% of Americans now identify as "spiritual but not religious", according to Pew Research—people seeking transcendence without institutional structure. The problem is that meaning-making has historically been a communal activity, not an individual one. Trying to construct meaning alone is like trying to speak a language only you know.

Vervaeke argues that the meaning crisis stems from losing traditional wisdom practices that cultivated ways of knowing beyond propositional knowledge. Pre-modern cultures had methods—contemplative practices, ritual, myth—for developing participatory and perspectival knowing. We've kept the rational-analytic mode while discarding the rest.

This creates what Vervaeke calls cognitive and existential homelessness. We have more information than ever but less wisdom about what matters. We can Google any fact but can't answer why anything should matter at all.

Add one more ingredient: the systematic capture and commodification of human attention. Every app, platform, and device is engineered to maximize engagement, which means hijacking the reward systems that once helped us navigate toward meaningful goals.

The average person now spends over seven hours daily on screens, much of it on platforms designed to deliver micro-hits of validation and distraction. These platforms don't create meaning—they substitute simulation for substance, replacing deep engagement with shallow stimulation.

Research suggests that CDC reports reveal significant increases in adult anxiety and depression, correlating with the rise of smartphone adoption and social media penetration. When your attention becomes the product, your capacity for sustained meaningful activity gets fragmented into scrollable moments.

Here's where things get interesting. Because while the meaning crisis is real and pervasive, it's also generating response and innovation. People aren't just suffering—they're experimenting with solutions.

The mindfulness revolution isn't just New Age hype. Rigorous research shows contemplative practices deliver measurable benefits: reduced anxiety, improved emotional regulation, enhanced cognitive flexibility, and increased life satisfaction. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) programs have been studied in over 200 clinical trials.

But Vervaeke emphasizes that mindfulness alone isn't enough. Traditional practices were embedded in comprehensive meaning-making frameworks. Extracting meditation from Buddhism is like extracting prayer from Christianity—you get some benefits but lose the context that made them transformative. What's needed is contemplative education that integrates these practices into coherent worldviews.

Traditional contemplative practices weren't about stress reduction—they were technologies for transforming consciousness. When divorced from their original frameworks, they provide relief but not transformation.

The On Being Project and similar initiatives are researching how contemplative practices can be taught in secular contexts while preserving their transformative potential. Early results suggest that practices explicitly aimed at cultivating meaning—not just stress reduction—show different and more durable outcomes.

Across the developed world, people are creating new forms of community to replace eroded traditional ones. Co-housing developments, maker spaces, mutual aid networks, and neighborhood pods are emerging as responses to isolation.

These aren't communes or utopian experiments. They're practical attempts to rebuild social infrastructure. Some use shared physical spaces. Others form around shared practices or values. What they have in common is intentionality—recognizing that community won't happen automatically and needs to be deliberately cultivated.

The success of these experiments varies, but research suggests that even modest increases in social connection improve health outcomes and longevity dramatically. The WHO now emphasizes that investing in social connection infrastructure may be one of the highest-impact public health interventions available.

Another frontier involves rethinking the relationship between work and meaning. The traditional model—work is obligation, meaning happens elsewhere—is being questioned. Some organizations are experimenting with structures that embed purpose into work itself: B-corporations that balance profit with social mission, worker cooperatives that give employees ownership and voice, and companies that organize around mission rather than extraction.

Research on happiness and policy suggests that governments should measure success by well-being rather than GDP growth. New Zealand, Iceland, and Bhutan have formally adopted well-being frameworks in policy making. The results are preliminary but promising: policies shift toward education, mental health services, community building, and environmental protection when well-being becomes the metric.

This doesn't mean abandoning economic growth, but subordinating it to human flourishing. GDP is increasingly recognized as a poor proxy for societal health. Countries that prioritize happiness metrics are discovering that some traditional drivers of GDP—like long commutes, excessive work hours, and consumption treadmills—actively undermine the goal.

Perhaps most intriguingly, there's renewed interest in pre-modern wisdom traditions not as belief systems but as technologies of meaning-making. Stoicism, Buddhism, indigenous practices, and mystical traditions from various religions are being studied for the cognitive and existential skills they cultivated.

"If we return to a society that truly values humility, wisdom, and shared humanity, we might begin to see a shift toward meaning, even within our modern constraints."

— John Vervaeke

Vervaeke's framework emphasizes 4E cognition—embodied, embedded, enacted, and extended. Meaning isn't just in your head. It emerges from how your body moves through space, how you're situated in environments, what practices you enact, and how you extend yourself through tools and relationships.

Traditional practices understood this intuitively. Ritual wasn't just symbolic—it was a technology for transforming cognition through embodied action. Contemplation wasn't passive—it was active training in attention and perception. Community wasn't just social—it was epistemological, a way of knowing through collective participation.

So what do you do with all this? The meaning crisis isn't something you solve alone. That's partly the problem—we've been told meaning is an individual achievement, something you find through introspection or buy through experiences.

But meaning is fundamentally relational. It emerges from connection—to people, to practices, to purposes larger than yourself. The good news is that means it's accessible. You don't need enlightenment or extraordinary circumstances. You need participation in meaningful communities and practices.

Start small. Find one practice—meditation, journaling, a creative pursuit—and commit to it not for results but for its own sake. Join one group organized around shared values or interests. Show up consistently. Meaning accumulates through sustained engagement, not peak experiences.

The strongest predictors of life satisfaction aren't wealth, status, or achievement. They're quality of relationships, sense of purpose, and engagement in meaningful activities—all cultivatable skills, not genetic gifts.

Research consistently shows that the strongest predictors of life satisfaction aren't wealth, status, or achievement. They're quality of relationships, sense of purpose, and engagement in activities that feel meaningful. These aren't genetic gifts or lucky circumstances—they're cultivatable skills.

The meaning crisis is revealing something important: material abundance was never the destination. It was supposed to be the foundation that enabled human flourishing. We built the foundation but forgot to construct the house. Now we're sleeping on concrete, wondering why it's so uncomfortable.

History suggests that crises like this catalyze transformation. The Axial Age—when Buddhism, Stoicism, Confucianism, and other wisdom traditions emerged simultaneously around 500 BCE—was a response to the collapse of earlier meaning systems. The Renaissance and Enlightenment were responses to the breakdown of medieval frameworks.

We're in another such transition. The old frameworks aren't coming back. The question is what emerges. Will we construct new wisdom traditions appropriate to a secular, pluralistic, technologically advanced civilization? Can we develop practices and institutions that cultivate meaning without coercion or dogma?

The experiments happening now—in contemplative science, community building, alternative economics, and wisdom recovery—are the early iterations. Most will fail. Some will succeed. Through trial and error, we'll gradually build out what comes after the meaning crisis.

The opportunity in front of us is unprecedented. For the first time in history, we can draw on the accumulated wisdom of all human cultures while using scientific methods to test what actually works. We can design meaning-generating practices and institutions with intentionality rather than inheriting them by accident.

But it requires recognizing that more material abundance won't solve this. The solution isn't on the other side of the next purchase, promotion, or pleasure. It's in recovering modes of being that our culture temporarily mislaid in the rush toward progress.

The meaning crisis isn't a bug in modern life. It's revealing that what we thought was the destination—comfort, choice, convenience—was always just the beginning. The real work starts when we ask: now that survival is handled, what are we for?

That question doesn't have one answer. It has seven billion answers, each discovered through the lived practice of creating lives worth living. The crisis is the call. How we respond will define not just individuals but the next chapter of human civilization.

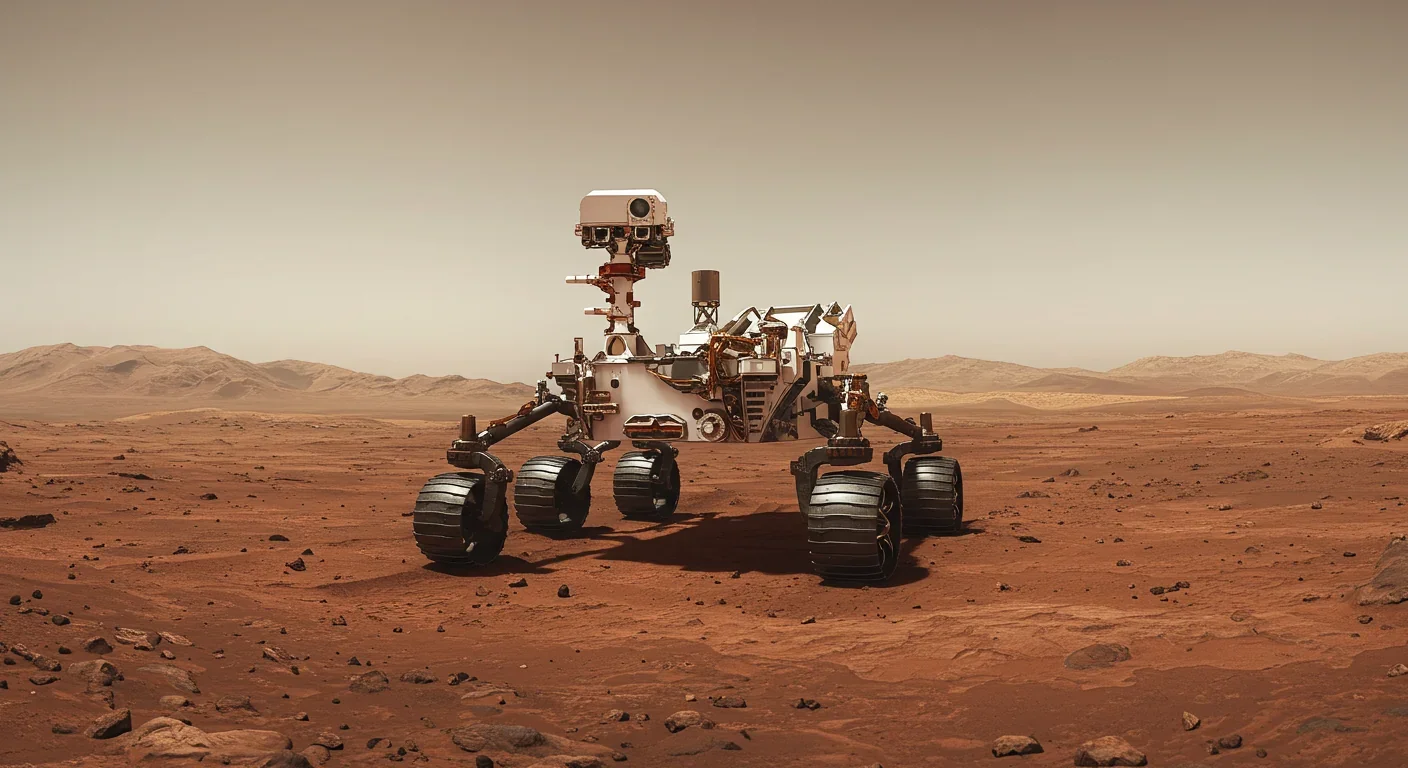

Curiosity rover detects mysterious methane spikes on Mars that vanish within hours, defying atmospheric models. Scientists debate whether the source is hidden microbial life or geological processes, while new research reveals UV-activated dust rapidly destroys the gas.

CMA is a selective cellular cleanup system that targets damaged proteins for degradation. As we age, CMA declines—leading to toxic protein accumulation and neurodegeneration. Scientists are developing therapies to restore CMA function and potentially prevent brain diseases.

Intercropping boosts farm yields by 20-50% by growing multiple crops together, using complementary resource use, nitrogen fixation, and pest suppression to build resilience against climate shocks while reducing costs.

Cryptomnesia—unconsciously reproducing ideas you've encountered before while believing them to be original—affects everyone from songwriters to academics. This article explores the neuroscience behind why our brains fail to flag recycled ideas and provides evidence-based strategies to protect your creative integrity.

Cuttlefish pass the marshmallow test by waiting up to 130 seconds for preferred food, demonstrating time perception and self-control with a radically different brain structure. This challenges assumptions about intelligence requiring vertebrate-type brains and suggests consciousness may be more widespread than previously thought.

Epistemic closure has fractured shared reality: algorithmic echo chambers and motivated reasoning trap us in separate information ecosystems where we can't agree on basic facts. This threatens democracy, public health coordination, and collective action on civilizational challenges. Solutions require platform accountability, media literacy, identity-bridging interventions, and cultural commitment to truth over tribalism.

Transformer architectures with self-attention mechanisms have completely replaced static word vectors like Word2Vec in NLP by generating contextual embeddings that adapt to word meaning based on surrounding context, enabling dramatic performance improvements across all language understanding tasks.