Why We Choose Impractical Partners: The Science of Love

TL;DR: Our brains respond more powerfully to one person's story than to statistics about millions. This identifiable victim effect drives charity donations and policy decisions, but it also creates ethical dilemmas about who gets help and why.

When you see a photograph of a single starving child, eyes wide and pleading, you feel something visceral. Your chest tightens. Maybe you reach for your wallet. But when someone tells you that 20 million people face famine, the number slides past like background noise. That's not callousness on your part—it's your brain doing what evolution wired it to do. Welcome to the identifiable victim effect, a cognitive quirk that shapes everything from charity donations to political policy, and understanding it might be the key to fixing some of humanity's biggest problems.

The identifiable victim effect is simple: people offer greater aid, empathy, and action toward a specific, identifiable individual than toward a vague statistical group facing the same crisis. Show someone a child named Rokia from Mali, and donations pour in. Present the same donors with abstract data about millions affected by drought, and wallets stay closed.

This isn't new information to researchers. Psychologists Deborah Small and George Loewenstein demonstrated this in a landmark 2003 study. When participants learned about a child needing medical treatment and were given details like her name, age, and photo, contributions spiked. Strip away those identifying details and present her as "a child among thousands," and donations plummeted—even though the need was identical.

But here's where it gets weird: the effect doesn't scale. If one identified victim prompts generous giving, surely two would double it, right? Wrong. Research shows that when you present people with two or more identified victims—names, photos, stories, the whole package—donations don't increase. Sometimes they actually decrease. Scientists call this "compassion fade," and it reveals something uncomfortable about human empathy: we're built for stories about individuals, not spreadsheets about populations.

Thomas Schelling, the Nobel Prize-winning economist, put it bluntly decades ago. He noted that we'll move heaven and earth to rescue a single trapped miner but struggle to fund systematic mine safety improvements that would save more lives. The trapped miner has a face, a family, a name. Statistical lives lack narrative traction.

The mechanism behind this bias runs deeper than simple preference. When you encounter a specific person in distress, your brain activates emotional processing centers. You imagine their suffering. You picture their relief if helped. This emotional engagement bypasses analytical thinking—the part of your brain that might calculate cost-effectiveness or compare competing needs.

Statistical victims trigger different neural pathways. Big numbers activate abstract reasoning rather than empathy. Your brain treats "20 million facing famine" more like a math problem than a human tragedy. This creates what psychologist Paul Slovic calls "psychic numbing"—the larger the number, the less we feel per individual. One death feels like a tragedy. A million becomes a statistic, just as the misattributed Stalin quote suggests.

The 2015 photo of Alan Kurdi demonstrated this effect at global scale. The three-year-old Syrian boy's body washed up on a Turkish beach, and the image ricocheted around the world. Within 24 hours, one migrant charity recorded a 15-fold increase in donations. Public pressure on European governments intensified overnight. Yet the Syrian refugee crisis had been escalating for years, with hundreds of thousands displaced and drowning in Mediterranean crossings. The statistics were available. The suffering was documented. But it took one identifiable child to trigger mass action.

Similar patterns emerged with Baby Jessica, the Texas toddler who fell down a well in 1987. Her 58-hour rescue captivated America and generated hundreds of thousands of dollars in donations to her family. Meanwhile, systematic child welfare programs struggled for funding. Ryan White, a teenager with AIDS, became the face of the epidemic in the 1980s, and his story helped pass the Ryan White Care Act—the largest federal program for people living with HIV/AIDS. Countless others suffered from the same disease, but Ryan had a story people could follow.

Nonprofits figured this out long ago. Walk through any major charity's marketing materials and you'll see the pattern. Save the Children doesn't lead with "millions of children lack clean water." They show you Maria, age 7, who walks three miles daily to fetch contaminated water that makes her sick. Sponsor programs thrive on this model—your $30 a month helps one specific child, complete with photos and letters, even though that money likely flows into a general fund supporting entire communities.

GoFundMe's data confirms what psychology predicts. Campaigns featuring a single person's story with photos, updates, and personal details vastly outperform generic appeals for the same cause. This works because identifiability creates what researchers call "singularity"—the sense that this one person's fate rests in your hands.

The approach isn't manipulation so much as pragmatic adaptation to human psychology. If abstract appeals don't generate resources needed to help people, then concrete stories become necessary. But this creates thorny problems.

First, there's the equity issue. Not all victims are equally identifiable or sympathetic. Research shows the effect strengthens when the victim is a child, shown in photographs, suffering from poverty rather than disease, and perceived as blameless. Victims who don't fit this template—adults, those whose suffering seems "their own fault," people in situations too complex for simple narratives—get less help regardless of need.

This bias ripples through policy. Politicians know that championing one sympathetic case generates more public support than addressing systemic issues affecting millions. The Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act passed largely because James Brady, Ronald Reagan's press secretary, became the identifiable face of gun violence after an assassination attempt. Meanwhile, comprehensive violence prevention addressing root causes languishes.

Media coverage follows similar patterns. A photogenic missing person sparks national obsession and massive search resources. Dozens of similar cases lacking that narrative appeal go unnoticed. This isn't conscious discrimination—it's the identifiable victim effect operating at scale, warping resource allocation toward whatever captures emotional attention.

The manipulation concern cuts deeper. Once you know this bias exists, using it to influence behavior raises ethical questions. Is it wrong to feature one suffering child when millions need help? If the single story generates more aid than statistics would, does the end justify the means? What about when the effect is weaponized for less noble purposes—political fearmongering, scapegoating, manufactured outrage?

The effect has limits. A study during the COVID-19 pandemic found that identifying victims in health messaging had no meaningful impact on protective behaviors like mask-wearing or hand-washing. When threats feel abstract or personally distant, even compelling individual stories may not overcome them.

Context matters too. A recent large-scale replication study found that the interaction between singularity and identifiability failed to replicate with diverse online samples. This suggests the effect may be less universal than originally thought, varying by cultural context, cause type, and audience characteristics.

Compassion fade creates another problem. Organizations competing for attention keep upping the emotional intensity. But there's only so much tragedy people can absorb before they disengage entirely. The endless parade of individual suffering stories can paradoxically lead to numbing rather than empathy—exactly the opposite of what's intended.

So how do you harness the identifiable victim effect ethically? The key is balancing emotional engagement with honest context.

Start with real stories that represent genuine broader patterns. Don't cherry-pick the most extreme or photogenic case; choose someone whose experience reflects what many face. Provide identifying details that humanize without exploiting. A name, age, and authentic quote work better than manipulative emotional appeals.

Connect the individual to the bigger picture. After introducing Maria and her water crisis, explain that she represents 2 million children in her region facing similar challenges. Help donors see that supporting Maria means supporting systemic solutions. This approach, called data-driven storytelling, combines narrative power with statistical literacy.

Be transparent about how contributions help. If donations go to a general fund, say so. If the featured individual is one example among many, make that clear. Respect your audience enough to trust them with complexity while still using narrative to create emotional connection.

Rotate your stories. Don't always feature children, or only certain demographics, or exclusively blameless victims. Show the full spectrum of people affected to combat the effect's inherent biases. This takes conscious effort because less "ideal" victims generate weaker responses—but it's necessary for equity.

Test your appeals. A/B testing isn't just for marketers. Nonprofits and advocacy groups can systematically compare approaches to see what generates both short-term donations and long-term engagement with systemic issues. Sometimes a hybrid approach—leading with a story but providing clear paths to learn about root causes—performs best.

Understanding the identifiable victim effect won't make it disappear. Evolution didn't wire us for global empathy at scale. Our brains developed in small groups where every face was known and every story mattered personally. Modern challenges require caring about millions we'll never meet, and that's psychologically unnatural.

But awareness creates options. When you notice yourself moved by one story while ignoring larger patterns, you can pause and ask: "What am I missing?" When crafting appeals for causes you care about, you can use narrative power responsibly rather than exploitatively. When evaluating policy, you can distinguish between emotionally compelling cases and evidence-based solutions.

The identifiable victim effect reveals both the best and worst of human nature. Our capacity for empathy is real and powerful—powerful enough that one child's story can mobilize the world. But that same empathy is maddeningly selective, easily manipulated, and poorly calibrated to the scale of modern suffering.

We can't think our way out of being human. But we can build systems that account for our cognitive quirks rather than being captured by them. That might mean funding decisions based on data while using stories to maintain public engagement. It could involve teaching statistical literacy alongside emotional intelligence. Maybe it requires designing new institutions that channel our narrative-driven empathy toward systemic change rather than isolated cases.

The answer isn't to stop telling stories. Stories are how we understand the world and each other. But in a century defined by challenges affecting billions—climate change, pandemics, mass displacement—we need to evolve beyond letting one face eclipse all others. The goal is keeping our hearts open to individual suffering while expanding our minds to grasp suffering at scale.

Because the truth is both simple and impossible to fully internalize: every number in those statistics is someone's Rokia. Someone's Ryan White. Someone's Alan Kurdi. Every one of the 20 million facing famine has a name, a story, people who love them and would move heaven and earth to save them.

We just don't know most of their names. And maybe, understanding why that matters so much to us is the first step toward making it matter less.

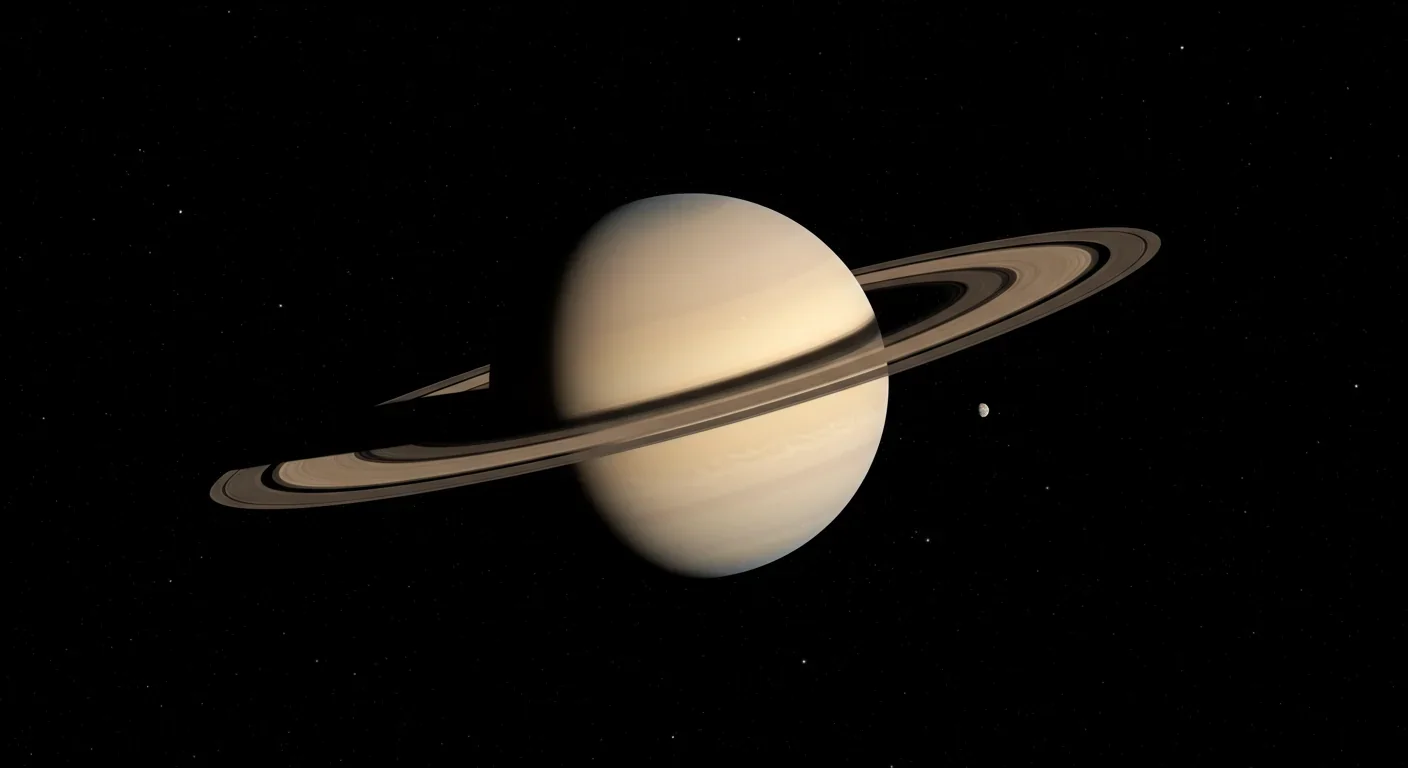

Saturn's iconic rings are temporary, likely formed within the past 100 million years and will vanish in 100-300 million years. NASA's Cassini mission revealed their hidden complexity, ongoing dynamics, and the mysteries that still puzzle scientists.

Scientists are revolutionizing gut health by identifying 'keystone' bacteria—crucial microbes that hold entire microbial ecosystems together. By engineering and reintroducing these missing bacterial linchpins, researchers can transform dysfunctional microbiomes into healthy ones, opening new treatments for diseases from IBS to depression.

Marine permaculture—cultivating kelp forests using wave-powered pumps and floating platforms—could sequester carbon 20 times faster than terrestrial forests while creating millions of jobs, feeding coastal communities, and restoring ocean ecosystems. Despite kelp's $500 billion in annual ecosystem services, fewer than 2% of global kelp forests have high-level protection, and over half have vanished in 50 years. Real-world projects in Japan, Chile, the U.S., and Europe demonstrate economic via...

Our attraction to impractical partners stems from evolutionary signals, attachment patterns formed in childhood, and modern status pressures. Understanding these forces helps us make conscious choices aligned with long-term happiness rather than hardwired instincts.

Crows and other corvids bring gifts to humans who feed them, revealing sophisticated social intelligence comparable to primates. This reciprocal exchange behavior demonstrates theory of mind, facial recognition, and long-term memory.

Cryptocurrency has become a revolutionary tool empowering dissidents in authoritarian states to bypass financial surveillance and asset freezes, while simultaneously enabling sanctioned regimes to evade international pressure through parallel financial systems.

Blockchain-based social networks like Bluesky, Mastodon, and Lens Protocol are growing rapidly, offering user data ownership and censorship resistance. While they won't immediately replace Facebook or Twitter, their 51% annual growth rate and new economic models could force Big Tech to fundamentally change how social media works.