Why We Choose Impractical Partners: The Science of Love

TL;DR: Asking someone for a favor makes them like you more, not less. This counterintuitive psychological phenomenon, known as the Benjamin Franklin Effect, works through cognitive dissonance: when people help you, their brains rationalize the action by deciding they must like you, strengthening bonds in both personal and professional relationships.

Imagine a world where asking for help doesn't make you look weak - it makes people like you more. It sounds backwards, but that's exactly what happens when you trigger the Benjamin Franklin Effect. This psychological phenomenon reveals that when someone does you a favor, they actually end up liking you more than before, not less. It's a quirk of human psychology that's been hiding in plain sight for centuries, and it's reshaping how we think about relationship-building in both personal and professional settings.

The effect takes its name from one of America's founding fathers, who discovered this counterintuitive truth through experience. In his autobiography, Franklin recounted a clever strategy he used to win over a political rival who refused to speak to him. Instead of trying to do the man a favor, Franklin asked to borrow a rare book from his personal library. The rival, surprised but flattered, agreed. When they next met, the man spoke cordially to Franklin, and they became lifelong friends. Franklin later wrote: "He that has once done you a kindness will be more ready to do you another than he whom you yourself have obliged."

So why does asking for help make people like you? The answer lies in cognitive dissonance, the uncomfortable feeling we get when our actions don't match our beliefs. When someone does you a favor - especially if they don't know you well - their brain faces a puzzle: "Why am I helping this person?" Since changing the action (the favor) is impossible once it's done, the mind adjusts the belief instead. "I must help them because I like them," the brain concludes, and suddenly, positive feelings toward you increase.

This mechanism was first validated scientifically in a landmark 1969 study by Jecker and Landy. Students participated in a contest where they could win money. After winning, they were divided into three groups: one group was asked directly by the researcher to return the money because he was running short on funds, another was asked by a secretary on behalf of the psychology department, and a third group wasn't asked at all. When asked to rate how much they liked the researcher, the students who were asked directly by him rated him significantly higher than the other two groups. The personal request triggered the effect, while the intermediary weakened it.

Cognitive dissonance theory, developed by Leon Festinger, explains that people strive for internal consistency between their beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors. When these elements conflict, we experience psychological discomfort. In Festinger's famous experiment, participants who were paid only $1 to lie about a boring task being enjoyable experienced strong dissonance - they had insufficient external justification for their dishonesty. To reduce discomfort, they actually changed their attitudes and rated the task as more enjoyable. Similarly, when you do someone a favor without obvious external motivation, your mind rationalizes it by deciding you must like them.

The Benjamin Franklin Effect isn't just historical trivia. Multiple studies across different cultures have confirmed that asking for favors increases likeability, even among people who initially dislike each other. One fascinating finding: the bigger the favor, the stronger the effect. When someone goes significantly out of their way to help you, cognitive dissonance forces them to align their perception of you with the effort they invested. The larger the inconvenience, the more positive the impression they form.

But there's a crucial caveat: authenticity matters. The favor request must be sincere, and the person helping must feel they're acting voluntarily. If someone senses manipulation or obligation, the effect can backfire. Research from 2020 showed that people overestimate the cost of saying no, which means they're more likely to comply with favor requests than we think. However, this social pressure can erode trust if the request feels exploitative.

Another critical finding: direct requests work best. When Franklin's rival lent the book, it was a personal interaction. The Jecker and Landy study demonstrated that having an intermediary (like the secretary) weakened the effect considerably. This tells us that personal connection amplifies the psychological impact.

Traditional advice about building relationships often focuses on doing favors for others. Be helpful. Be generous. Offer value first. While these strategies work through the principle of reciprocity - people feel obliged to return favors - the Benjamin Franklin Effect operates differently. It doesn't require the other person to reciprocate. The simple act of helping you is enough to shift their feelings.

This insight transforms how we approach networking, team-building, and even conflict resolution. Dale Carnegie interpreted the effect as a signal of value: when you ask someone for their expertise or insight, you communicate that you respect their knowledge. This creates admiration that amplifies the effect beyond simple reciprocity. Asking a colleague, "Could you help me understand this approach you used?" simultaneously compliments their skill and invites them into a collaborative relationship.

In professional settings, salespeople have adopted this strategy. Instead of offering to help a potential client, a savvy salesperson might ask the client for assistance - perhaps requesting feedback on a proposal or insight into industry trends. This "pure favor" builds likability that enhances the ability to earn the client's time and investment later.

The workplace application extends to leadership. Managers who occasionally ask team members for advice (genuinely, not performatively) can strengthen bonds. "I value your perspective on this challenge we're facing" isn't just flattery - it's an invitation to contribute that makes the employee feel useful, trusted, and connected.

So how do you leverage this effect ethically and effectively? Start small. The best favors are low-effort requests that make the other person feel capable and valued. Examples include:

Ask for advice: "Can I get your opinion on this?" works in nearly every context. Advice-seeking opens doors to deeper, more collaborative relationships because it positions the other person as an expert.

Request recommendations: "Do you know a good resource for learning X?" This is easy to fulfill and flattering.

Seek introductions: "Would you mind introducing me to someone in your network who does Y?" This shows you trust their judgment.

Borrow something small: Like Franklin's book, borrowing an item creates a personal connection point when you return it.

The key is that the favor should never feel burdensome. Use polite, open-ended language that gives the person an easy out: "If you have time..." or "No pressure, but..." This preserves the sense of voluntary action that's essential for the effect to work.

Timing matters too. The effect is strongest when you're trying to build a relationship with someone neutral or even mildly negative toward you. If someone already likes you, asking for favors reinforces the bond but doesn't create the same cognitive shift. Conversely, if someone actively dislikes you, starting with a massive favor request will probably fail - begin with the smallest possible ask and build from there.

Like any psychological principle, the Benjamin Franklin Effect has limitations and risks. Over-asking can definitely backfire. If you constantly request favors without reciprocating or showing gratitude, people will perceive you as selfish or manipulative. The effect works because the favor-giver rationalizes their kindness as genuine affection, but repeated exploitation breaks that illusion.

Power dynamics complicate things too. In mentor-protégé relationships, for instance, the effect can inadvertently make the protégé feel awkward if they're always receiving help from someone with more influence. The imbalance doesn't allow for the mutual exchange that sustains healthy relationships.

Cultural context matters as well. While the effect has been confirmed across cultures, the types of favors considered appropriate vary widely. In some cultures, asking for help too quickly might seem presumptuous, while in others, refusing a request for help could be seen as rude. Understanding these nuances prevents misapplication.

There's also the ethical consideration: should you deliberately trigger this effect to manipulate someone's feelings? The line between strategic relationship-building and manipulation isn't always clear. The difference lies in intent and reciprocity. If you're asking for favors solely to make someone like you, without genuine need or intention to build a mutually beneficial relationship, that crosses into manipulation.

Recent research has added another layer to our understanding. Studies show that performing acts of kindness activates the brain's reward system, releasing feel-good chemicals like dopamine and oxytocin. This means favor-givers experience a biochemical boost that reinforces their positive feelings toward you. It's not just cognitive dissonance - there's actual neurochemical reinforcement happening.

This creates what psychologists call a positive feedback loop. When someone helps you and feels good about it, they're more likely to help again. Each interaction strengthens the neural pathways associated with positive feelings toward you. Over time, this builds genuine affection that goes beyond the initial cognitive adjustment.

The health implications are fascinating too. Research indicates that both asking for and granting favors connects you to your extended social network, which positively affects health and longevity. Strong social bonds are one of the most reliable predictors of wellbeing, and the Benjamin Franklin Effect offers a counterintuitive path to building them.

It's important to understand how the Benjamin Franklin Effect differs from standard reciprocity. Reciprocity is straightforward: I do something for you, you feel obligated to return the favor. It's transactional. The Benjamin Franklin Effect is transformational - it changes the favor-giver's internal feelings about you, independent of any expectation of return.

The Psychology of Reciprocity teaches us that giving creates obligation in the recipient. But the Franklin Effect shows that the act of giving also changes the giver. This dual mechanism makes favor exchanges particularly powerful for relationship-building. When you ask someone for help and later reciprocate, you're activating both principles: they like you more because they helped you (Franklin Effect), and they feel you're trustworthy because you returned the favor (reciprocity).

Understanding this distinction lets you be more strategic. If your goal is simply to get someone to do something for you later, standard reciprocity (doing them a favor first) works fine. But if your goal is to genuinely shift someone's emotional stance toward you, asking them for a favor triggers deeper psychological change.

Adam Grant, in his book Give and Take, introduced the concept of the "Five-Minute Favor" - small acts of kindness that require minimal time but create significant value. This framework pairs perfectly with the Benjamin Franklin Effect. When you ask someone for a five-minute favor, you make it easy for them to say yes, trigger the psychological effect, and create an opportunity to reciprocate later.

Examples of five-minute favors include: making an introduction, sharing a relevant article, providing quick feedback on an idea, or answering a specific question in your area of expertise. These requests are substantial enough to trigger cognitive dissonance but not so large that they create burden or resentment.

In the digital age, this becomes even more accessible. A LinkedIn introduction, a retweet, a brief email reply - these tiny acts accumulate into relationship capital. The key is being genuinely grateful and following up. When someone takes five minutes to help you, acknowledge it specifically and, when appropriate, find ways to return the favor.

For leaders and managers, the Benjamin Franklin Effect offers a powerful tool for team cohesion. Traditional leadership advice emphasizes being helpful and available, but asking team members for their input and assistance can be equally valuable. When a leader says, "I need your expertise on this problem," it accomplishes several things:

1. It signals respect for the employee's skills

2. It makes the employee feel valued and needed

3. It triggers the Benjamin Franklin Effect, strengthening the emotional bond

4. It models vulnerability and collaborative problem-solving

This doesn't mean managers should abdicate responsibility or constantly lean on their teams inappropriately. It means recognizing that showing you value someone's contribution by asking for it can be more bonding than always being the helper.

The same principle applies to building cross-functional relationships. Instead of offering your marketing expertise to the engineering team unsolicited, ask them to explain a technical challenge they're facing. Your genuine interest and the act of them teaching you strengthens the connection more than offering help might.

As we move into an era of increasing digital interaction and social fragmentation, understanding how to build genuine human connection becomes more valuable, not less. The Benjamin Franklin Effect reminds us that vulnerability - admitting we need help - can be a strength. It challenges the modern ethos of self-sufficiency and "never showing weakness."

Emerging research is exploring how the effect translates to digital interactions. Does asking for help in an email trigger the same response as an in-person request? Preliminary findings suggest the effect persists online but is slightly weaker, emphasizing again the importance of personal connection.

There's also growing interest in how the effect could be applied to conflict resolution and peacebuilding. If asking former adversaries for small favors can shift their perceptions, it might offer a pathway to de-escalation in polarized environments. Imagine communities where opposing groups are encouraged to engage in small mutual assistance - could this psychological mechanism help bridge divides?

The Benjamin Franklin Effect is neither good nor bad - it's simply a feature of human psychology. What matters is how we use it. Applied ethically, it's a tool for building authentic relationships, strengthening teams, and connecting across differences. Applied manipulatively, it becomes a way to exploit people's psychological tendencies for selfish gain.

The ethical application requires three elements:

1. Genuine need or interest: Ask for favors you actually want or need, not just to trigger the effect

2. Reciprocity over time: Be willing to help others in return, creating balanced relationships

3. Gratitude and acknowledgment: Genuinely appreciate the help you receive

When Franklin asked his rival for the book, he genuinely wanted to read it. The psychological effect was a fortunate byproduct, not the primary goal. This authenticity is what made it work.

Understanding the Benjamin Franklin Effect gives us insight into why connection sometimes forms in unexpected ways. It explains why the colleague who helped you move apartments becomes a closer friend, or why the mentor who asks for your perspective feels more like an equal. It reveals that the path to someone's heart might just be letting them help you along the way.

So next time you're tempted to prove your worth by offering help, consider asking for it instead. You might be surprised how much people enjoy being useful - and how much closer they feel to you afterward. Just make sure you mean it, keep it small, and always say thank you. That's the magic formula for turning small acts of kindness into lasting bonds of trust.

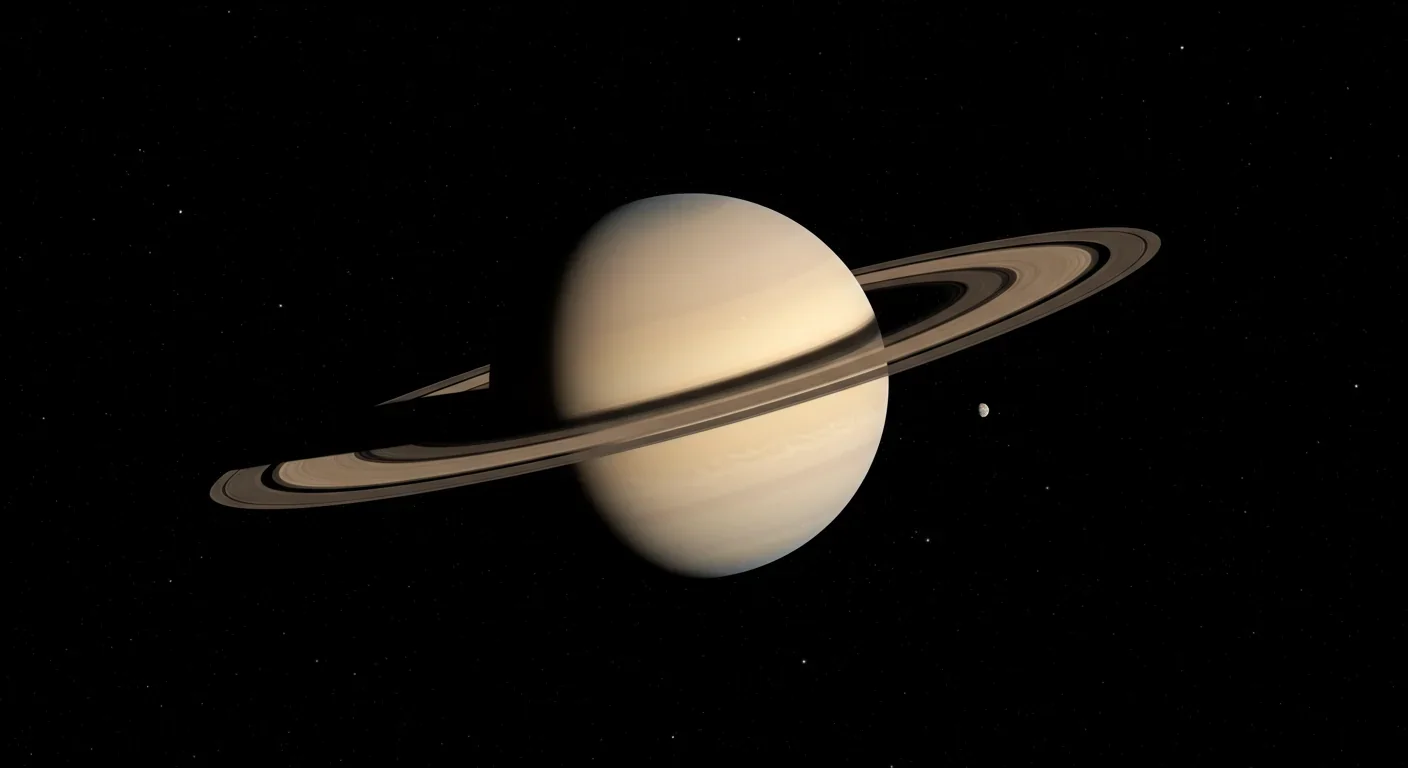

Saturn's iconic rings are temporary, likely formed within the past 100 million years and will vanish in 100-300 million years. NASA's Cassini mission revealed their hidden complexity, ongoing dynamics, and the mysteries that still puzzle scientists.

Scientists are revolutionizing gut health by identifying 'keystone' bacteria—crucial microbes that hold entire microbial ecosystems together. By engineering and reintroducing these missing bacterial linchpins, researchers can transform dysfunctional microbiomes into healthy ones, opening new treatments for diseases from IBS to depression.

Marine permaculture—cultivating kelp forests using wave-powered pumps and floating platforms—could sequester carbon 20 times faster than terrestrial forests while creating millions of jobs, feeding coastal communities, and restoring ocean ecosystems. Despite kelp's $500 billion in annual ecosystem services, fewer than 2% of global kelp forests have high-level protection, and over half have vanished in 50 years. Real-world projects in Japan, Chile, the U.S., and Europe demonstrate economic via...

Our attraction to impractical partners stems from evolutionary signals, attachment patterns formed in childhood, and modern status pressures. Understanding these forces helps us make conscious choices aligned with long-term happiness rather than hardwired instincts.

Crows and other corvids bring gifts to humans who feed them, revealing sophisticated social intelligence comparable to primates. This reciprocal exchange behavior demonstrates theory of mind, facial recognition, and long-term memory.

Cryptocurrency has become a revolutionary tool empowering dissidents in authoritarian states to bypass financial surveillance and asset freezes, while simultaneously enabling sanctioned regimes to evade international pressure through parallel financial systems.

Blockchain-based social networks like Bluesky, Mastodon, and Lens Protocol are growing rapidly, offering user data ownership and censorship resistance. While they won't immediately replace Facebook or Twitter, their 51% annual growth rate and new economic models could force Big Tech to fundamentally change how social media works.