White Dwarf Spectroscopy Reveals Destroyed Exoplanets

TL;DR: The overview effect—a profound psychological shift experienced when viewing Earth from space—has transformed astronauts' consciousness for over 50 years, fostering environmental activism and global cooperation. Neuroscience reveals it triggers measurable brain changes in awe and self-transcendence systems, with 70% of astronauts reporting lasting conservation commitment. As commercial spaceflight expands, this perspective could reshape how humanity addresses climate change and planetary stewardship—but critical questions remain about access, cultural framing, and whether we can cultivate a planetary consciousness without leaving Earth.

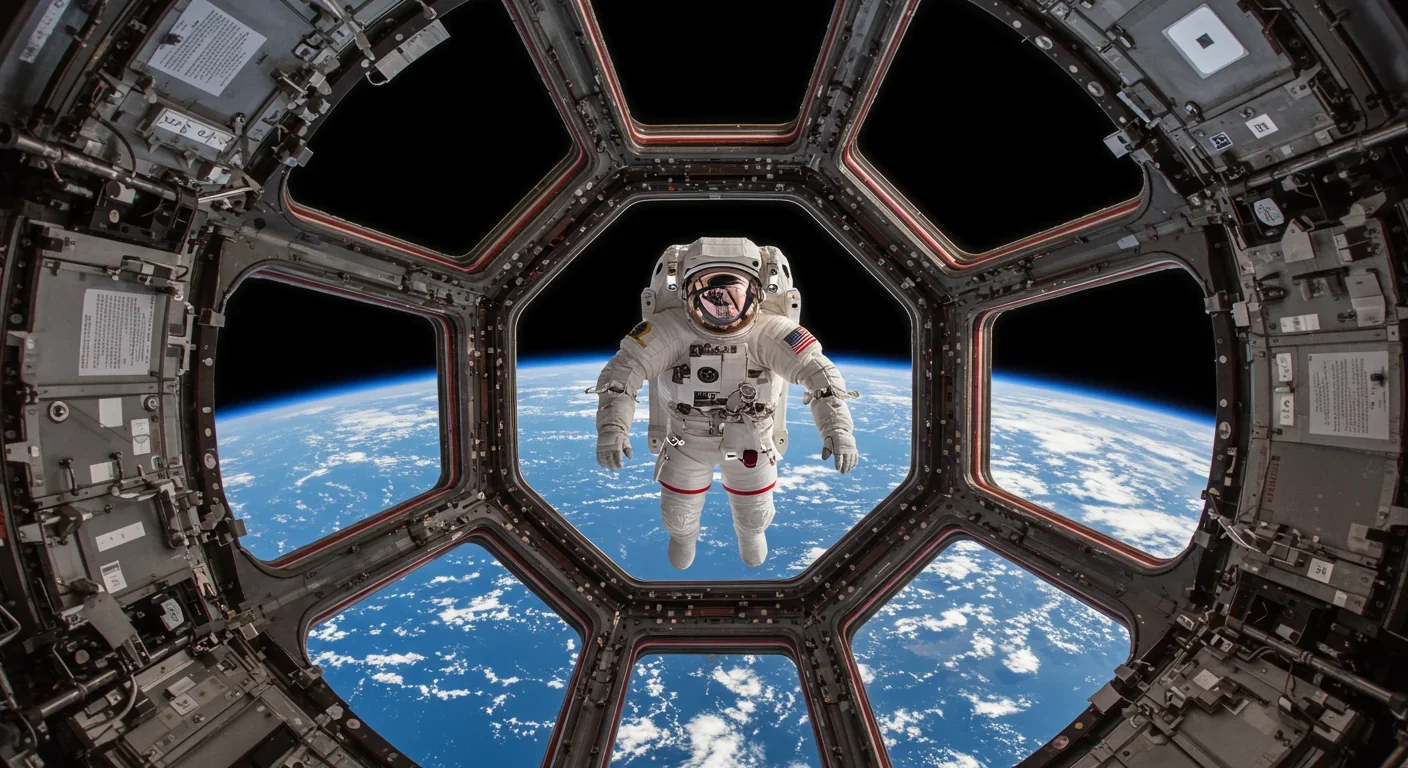

By 2030, commercial space tourism will have sent thousands of civilians beyond Earth's atmosphere—and when they return, many will never see our planet the same way again. The overview effect, a profound psychological shift experienced by astronauts viewing Earth from space, has quietly influenced environmental policy, international cooperation, and our understanding of human consciousness for over five decades. Now, as space becomes accessible to non-astronauts, this cosmic perspective may reshape how civilization confronts its greatest challenges.

On December 24, 1968, Apollo 8 astronaut William Anders turned his camera toward a small blue sphere rising above the Moon's desolate horizon. "Oh my God, look at that picture over there!" he exclaimed. "There's the Earth comin' up. Wow, is that pretty!" That photograph, later known as Earthrise, became what nature photographer Galen Rowell called "the most influential environmental photograph ever taken." But the image's power wasn't just aesthetic—it captured a cognitive transformation that would alter human consciousness itself.

Frank White coined the term "overview effect" in his 1987 book The Overview Effect: Space Exploration and Human Evolution, but the phenomenon existed long before it had a name. When Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first human in space in 1961, he radioed back: "People of the world, let us safeguard and enhance this beauty, and not destroy it!" Apollo 11's Michael Collins noted that Earth "projected an air of fragility." Apollo 14's Edgar Mitchell described "an explosion of awareness" that induced overwhelming unity and responsibility. Across missions, nationalities, and decades, astronauts reported strikingly similar experiences: seeing Earth without borders, feeling profound interconnectedness, and returning with an urgent commitment to planetary stewardship.

Recent surveys reveal the breadth of this transformation. A 2018 study of 39 astronauts found statistically significant increases in perceived Earth beauty and fragility, with moderate changes correlating directly to subsequent environmental activism. Approximately 67% of astronauts surveyed report experiencing some form of the overview effect. A 2021 study in the Environmental Psychology Journal found that 70% of astronauts reported heightened commitment to conservation after their missions. These aren't casual impressions—they're measurable psychological shifts with lasting behavioral consequences.

The overview effect isn't the first time a technological breakthrough has fundamentally altered human consciousness. The invention of the telescope in the early 17th century transformed our cosmic perspective, revealing that Earth was neither flat nor the center of the universe. The camera enabled us to capture moments in time, changing how we remember and construct narratives. Air travel shrank distances and made the world feel smaller, fostering globalization and cultural exchange.

But space travel introduced something qualitatively different: the first external view of our entire planetary home. For the first time in human evolution, members of our species could physically leave Earth's surface and observe it as a whole system. This wasn't a conceptual or intellectual shift—it was visceral, immediate, and overwhelming.

The Earthrise photograph exemplifies this power. Published in Life magazine's 1969 book 100 Photographs that Changed the World, it became the cover of the Spring 1969 Whole Earth Catalog. Historians credit the image with catalyzing the modern environmental movement. The first Earth Day was celebrated in 1970, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency was created the same year. The photograph made Earth's fragility tangible in ways scientific reports never could.

William Anders himself underwent a profound personal transformation. In a 2018 interview, he admitted that taking Earthrise "really undercut my religious beliefs." He became close friends with atheist scientist Richard Dawkins, shifting from a religious to a scientific worldview. "We set out to explore the moon and instead discovered the Earth," Anders reflected—a statement that captures the unexpected nature of this cognitive revolution.

This pattern repeats throughout history: technologies designed for one purpose often deliver unintended psychological and cultural consequences. Nuclear weapons were built to win wars but created an existential awareness that reshaped international relations. Social media was built to connect people but fundamentally altered how we construct identity and community. Space exploration was designed to demonstrate technological supremacy during the Cold War—but it delivered a perspective that transcended national borders entirely.

What happens in the brain when an astronaut experiences the overview effect? Recent neuroscience research reveals that this isn't merely a poetic response—it's a specific neural phenomenon rooted in the brain's awe and self-transcendence systems.

Awe begins with attentional capture: the brain's ventral tegmental area floods the system with dopamine, creating a powerful reward signal that locks attention onto the overwhelming stimulus. Simultaneously, the amygdala—the brain's emotional amplifier—heightens sensory vividness, making every detail feel more intense and memorable. The hippocampus encodes these vivid details into long-term memory, ensuring the experience leaves a lasting imprint.

But the most fascinating change occurs in the prefrontal cortex, the brain's executive control center. During moments of wonder and awe, the prefrontal cortex exhibits what neuroscientists call "transient hypofrontality"—a temporary reduction in top-down control. This allows the brain to step out of its usual narrative, analytical mode and into direct, immersive sensory experience. The usual mental chatter quiets, and the boundary between self and environment begins to blur.

Functional MRI studies have pinpointed even more specific changes during self-transcendent experiences like the overview effect. Research by Andrew Newberg and colleagues found measurable decreases in activity within the posterior superior parietal and inferior parietal lobes—brain regions associated with self-referential processing and the sense of a bounded self. When these areas quiet down, people report feeling less separate from their surroundings and more connected to something larger than themselves.

A 2025 pilot study by Krause-Sorio and colleagues used fMRI to examine how different types of awe-inducing experiences affect the brain. Participants viewed AI-generated art, sweeping nature scenes, and cosmic imagery designed to prompt meditation on universal connectedness. Nature scenes quieted stress circuits while sharpening the visual cortex. Cosmic imagery activated the fusiform gyri, postcentral gyri, and hippocampus—areas involved in memory consolidation and self-reflection. The study confirmed that contemplating the universe engages perception, memory, and introspection networks simultaneously, blurring the boundary between self and environment.

This neurobiological architecture explains why the overview effect is so powerful and persistent. It's not just an emotional reaction—it's a fundamental reconfiguration of how the brain processes self, environment, and meaning. The experience leaves "fingerprints" on neural pathways, altering how astronauts perceive their relationship to Earth long after they return.

The overview effect doesn't stay confined to the astronaut's mind—it radiates outward into behavior, activism, and policy. Understanding this ripple effect requires examining specific cases where the experience translated into tangible societal change.

Ron Garan, who spent 178 days aboard the International Space Station and traveled over 71 million miles in 2,842 orbits, returned with a stark message. "When I looked out the window of the International Space Station, I saw the paparazzi-like flashes of lightning storms, I saw dancing curtains of auroras that seemed so close it was as if we could reach out and touch them," Garan recalled. "And I saw the unbelievable thinness of our planet's atmosphere. In that moment, I was hit with the sobering realization that that paper-thin layer keeps every living thing on our planet alive."

Garan concluded that humanity is "living a lie"—prioritizing economic growth over planetary health. "We need to move from thinking economy, society, planet to planet, society, economy," he argued. "That's when we're going to continue our evolutionary process." Garan has since become a vocal advocate for reorienting human priorities around ecological sustainability rather than GDP growth.

Edgar Mitchell, Apollo 14 astronaut, experienced a similarly transformative moment during his return from the Moon. "You develop an instant global consciousness, a people orientation, an intense dissatisfaction with the state of the world, and a compulsion to do something about it," Mitchell said in a 1971 interview. He founded the Institute of Noetic Sciences (IONS) in 1973 to explore consciousness, ecological stewardship, and the intersection of science and subjective experience. His activism extended into environmental policy advocacy and interdisciplinary research bridging psychology, ecology, and consciousness studies.

Nicole Stott, who spent time aboard the ISS, described the cupola—a seven-window observation module—as transformative. "It is a really impressive place and it has changed the view that you get from flat, Earth-facing windows," Stott said. "You really get the curvature of the Earth, and you get much more of a feeling of a planet hanging in space." NASA later confirmed that the cupola's design, originally intended for operational tasks, became primarily used for "Earthgazing"—a relaxation practice that reduced stress and enhanced creativity among astronauts. Research by Annabita Nezami found that Earthgazing motivates positive psychological growth by diminishing cognitive and emotional stress and cultivating emotions like belonging, gratitude, reverence, and humility.

The Fragile Oasis initiative, founded in 2005 by astronauts who experienced the overview effect, epitomizes this activist impulse. The organization promotes planetary stewardship by sharing astronauts' perspectives with the public, fostering cross-cultural collaboration, and supporting environmental projects. Its founders explicitly framed their mission as translating the overview effect into collective action.

These individual transformations have influenced broader cultural and political outcomes. The Earthrise photograph didn't just inspire activists—it was wielded by policymakers to justify environmental regulation. The image appeared in Congressional hearings, UNESCO campaigns, and educational materials worldwide. NASA's subsequent Earth observation programs, designed to monitor climate change and ecosystem health, were partly justified by the moral imperative that Earthrise symbolized.

More recently, the Artemis 2 mission patch incorporates cloud patterns from the original Earthrise photograph, signaling a continued symbolic link between space exploration and environmental stewardship. This design choice reflects NASA's recognition that space missions carry not just scientific but also moral and cultural weight.

The overview effect offers profound benefits at individual, organizational, and civilizational scales. Understanding these promises helps explain why the phenomenon has attracted interest far beyond space agencies.

Personal Transformation and Mental Health:

Studies confirm that awe experiences reduce anxiety, increase prosocial behavior, and enhance overall well-being. For astronauts, Earthgazing has been shown to reduce cognitive and emotional stress, as indicated by changes in vagal tone and increased positive emotions. Research by Meier and colleagues (2020) demonstrated relationships between vagal tone, creativity, and divergent thinking, suggesting that the emotional benefits of Earthgazing are physiologically measurable. In extreme environments like space, where isolation and confinement create intense psychological pressure, the overview effect serves as a psychological buffer—offering astronauts a source of meaning, connection, and emotional renewal.

Environmental Stewardship:

The most obvious promise is heightened ecological awareness. When borders disappear and Earth appears as a single fragile system, environmental degradation ceases to feel like a distant abstraction. It becomes personal. Astronauts consistently report that seeing Earth's thin atmosphere and delicate biosphere fosters a visceral commitment to conservation. This isn't just sentiment—it translates into measurable activism. The 70% of astronauts who reported increased conservation commitment post-mission have gone on to advocate for climate policy, renewable energy, and habitat preservation.

Global Cooperation:

The overview effect dissolves national divisions. As Emily Calandrelli, a Blue Origin NS-28 passenger, put it: "We got to weightlessness, I immediately turned upside down and looked at the planet and then there was so much blackness. There was so much space. I didn't expect to see so much space, and I kept saying that's our planet! That's our planet! It was the same feeling I got when my kids were born." This sense of collective belonging has implications for international relations. If leaders and citizens alike could internalize a planetary perspective, conflicts rooted in territorial disputes or national pride might seem trivial against the backdrop of cosmic isolation.

Creativity and Innovation:

NASA's decision to design spacecraft with dedicated Earthgazing spaces—like the ISS cupola—wasn't just aesthetic. Research suggests that exposure to awe-inducing experiences enhances divergent thinking and problem-solving. Astronauts report that time spent contemplating Earth sparks insights, novel ideas, and creative breakthroughs. This has practical implications: organizations designing for extreme environments (submarines, Antarctic stations, long-duration space missions) can enhance productivity by incorporating spaces that foster awe and relaxation.

Philosophical and Spiritual Renewal:

For many astronauts, the overview effect provides a sense of meaning and connection that transcends religious or ideological frameworks. Mitchell's founding of IONS reflected his belief that the experience opened new questions about consciousness, interconnectedness, and humanity's place in the universe. The effect invites a shift from anthropocentric to biocentric or even cosmocentric worldviews—frames of reference that could inform ethics, governance, and long-term planning.

While the overview effect's promise is inspiring, critical scholars and ethicists have raised important concerns about how the narrative is constructed, communicated, and potentially weaponized.

The Privilege Problem:

Only around 500 people alive today have been to space. This makes the overview effect one of the most exclusive psychological experiences on Earth. As commercial space tourism expands, access will remain limited to the ultra-wealthy. If the overview effect is framed as a prerequisite for environmental consciousness, it risks creating a two-tier moral hierarchy: those who have "seen the light" from orbit and those who remain earthbound and presumably less enlightened. This could undermine grassroots environmental movements led by people who have never left their own countries, let alone the planet.

The Narrative's Political Origins:

Jordan Bimm's critical scholarship reveals that the overview effect emerged from Cold War military systems thinking. Frank White's 1987 book synthesized ideas from Gaia theory, Buckminster Fuller's "Spaceship Earth," and military history—frameworks rooted in control, optimization, and top-down management. Bimm argues that the overview effect is not a purely natural psychological phenomenon but a culturally constructed narrative shaped by specific political and ideological contexts. This doesn't invalidate astronauts' experiences, but it complicates the claim that the effect is universal or apolitical.

Moreover, the narrative can be co-opted. Space colonization advocates sometimes invoke the overview effect to justify extraterrestrial expansion, framing it as humanity's evolutionary destiny. This rhetorical move risks using the language of planetary stewardship to justify resource extraction on other worlds—a contradiction that deserves scrutiny.

Cultural Specificity:

Bimm's critique also highlights that the overview effect may vary culturally. While Western astronauts consistently describe feelings of unity and environmental responsibility, these interpretations are filtered through cultural lenses. Indigenous cosmologies, for instance, have long emphasized interconnectedness and planetary stewardship without requiring a view from space. If the overview effect is presented as the only path to ecological consciousness, it marginalizes non-Western epistemologies that have cultivated similar insights for millennia.

Virtual Reality's Limitations:

Researchers have attempted to replicate the overview effect using virtual reality simulations. Projects like "The Infinite" VR experience, SpaceBuzz, and large Earth model tours have aimed to democratize access. A 2019 VR study found that participants reported minor awe and connection, but the transformative intensity of actual spaceflight remained elusive. Why? VR lacks the visceral context: the isolation, the zero gravity, the knowledge that one is truly suspended in the void. As one analysis noted, VR produces a weaker effect because it's missing the existential stakes.

This raises a philosophical question: Can we truly internalize a planetary perspective without leaving the planet? Or does the overview effect require the raw, unmediated encounter with Earth's fragility from the vastness of space?

Mental Health Risks:

Not every astronaut experiences the overview effect positively. William Shatner, after his 2021 Blue Origin flight, admitted: "I realized I was in grief for the Earth." The intensity of seeing Earth's vulnerability can trigger sadness, anxiety, and a sense of helplessness. Commercial space tourism operators now include psychological preparation and coping strategies for overview effect experiences in their training programs—acknowledging that the phenomenon can be destabilizing.

The overview effect's narrative has been dominated by American and Russian astronauts, but as space access expands globally, diverse cultural perspectives are emerging.

Eastern Philosophies and Interconnectedness:

Many Eastern philosophies—Buddhism, Taoism, Hinduism—have long emphasized the illusion of the separate self and the interconnectedness of all life. For astronauts from these traditions, the overview effect may feel less like a revelation and more like a confirmation of existing beliefs. Japanese astronaut Mamoru Mohri, for example, described his spaceflight as reinforcing Buddhist concepts of interdependence and impermanence. This suggests that the overview effect might resonate differently depending on pre-existing worldviews.

Indigenous Cosmologies:

Many Indigenous cultures maintain cosmologies that view Earth as a living system deserving reverence and care. The concept of "Mother Earth" or "Pachamama" in Andean traditions embodies a planetary perspective without requiring spaceflight. Indigenous environmental activists have pointed out that the overview effect, while valuable, should not overshadow millennia-old ecological wisdom that has sustained human communities in balance with nature.

Non-Western Space Programs:

As China, India, the UAE, and other nations expand their space programs, astronauts from these countries are adding new voices to the overview effect narrative. Chinese astronaut Liu Yang described her first view of Earth as reinforcing a sense of collective responsibility and pride in humanity's achievements. Indian astronaut Rakesh Sharma, when asked how India looked from space, famously replied, "Saare Jahan Se Achha" ("Better than the whole world")—a response that blended national pride with cosmic perspective.

These diverse testimonies suggest that the overview effect is not monolithic. It's filtered through language, culture, and prior beliefs. Recognizing this diversity prevents the narrative from becoming a Western-centric imposition and opens space for cross-cultural dialogue about planetary stewardship.

International Cooperation vs. Competition:

The International Space Station itself embodies a tension: astronauts from competing nations (the U.S., Russia, Europe, Japan, Canada) collaborate daily, sharing the same cupola and the same view of Earth. This cooperation has fostered personal friendships and mutual respect that transcend geopolitics. However, as space becomes increasingly commercialized and militarized, questions arise: Will the overview effect inspire continued cooperation, or will national rivalries extend into orbit?

The Artemis Accords, which outline principles for lunar exploration, emphasize transparency, interoperability, and peaceful use—values arguably influenced by the cooperative spirit the overview effect fosters. But competing lunar and Mars missions from the U.S., China, and private companies could test whether this spirit endures under economic and strategic pressure.

As commercial spaceflight expands and thousands of civilians experience the overview effect, society must prepare to integrate these experiences into broader cultural and institutional frameworks.

Media Literacy and Critical Consumption:

The overview effect will be mediated through images, videos, and testimonials shared on social media. Learning to distinguish authentic experiences from marketing hype or politically motivated narratives will be crucial. Educators and media platforms should teach critical consumption skills, encouraging audiences to ask: Who is telling this story? What's being emphasized or omitted? What interests does this narrative serve?

Psychological Preparation and Integration:

Commercial space tourism operators are already incorporating psychological training, including meditation, coping strategies, and post-flight integration support. These practices should be expanded and studied rigorously. Just as athletes debrief after competitions and soldiers receive post-deployment counseling, space tourists should have access to frameworks that help them process and translate their experiences into constructive action.

Designing for Awe:

Architects, urban planners, and experience designers can apply insights from the overview effect to create Earthbound environments that foster awe and planetary thinking. This could include immersive planetarium experiences, VR simulations integrated with biofeedback and AI to maximize therapeutic impact, and public spaces designed to evoke wonder and reflection. Research into affective computing and adaptive VR environments suggests that future technologies could create personalized awe experiences tailored to individual psychological profiles.

Educational Curricula:

Schools and universities should integrate the overview effect into curricula across disciplines—environmental science, psychology, ethics, art, and literature. Students should explore questions like: What does it mean to have a planetary perspective? How can we cultivate ecological consciousness without spaceflight? What responsibilities come with seeing Earth as fragile?

Policy and Governance:

Policymakers should consider how the overview effect can inform climate policy, international cooperation, and long-term planning. For example, virtual reality simulations of Earth from space could be used in diplomatic settings to foster empathy and shared purpose. Environmental impact assessments could incorporate visual representations of Earth's fragility to make abstract data emotionally resonant.

Cultivating Earthbound Awe:

Ultimately, not everyone will go to space—and they shouldn't need to. Research into Earthbound awe experiences—stargazing, wilderness immersion, meditation on nature—suggests that similar psychological shifts can occur without leaving the planet. Naturalist John Muir wrote, "In every walk with nature, one receives far more than he seeks." Cultivating this receptivity to wonder in everyday life may be the most democratic path to a planetary perspective.

As Larissa Scherrer aptly put it: "We don't need to float 250 miles above our planet to understand its fragility and interconnectedness. We just need to start thinking like those who have."

The overview effect represents one of humanity's most profound psychological discoveries: that seeing Earth from space can fundamentally reconfigure consciousness, values, and behavior. From Yuri Gagarin's 1961 flight to today's commercial tourists, astronauts have returned with strikingly consistent messages—Earth is fragile, borders are illusions, and humanity shares a common home.

Neuroscience has begun mapping the mechanisms: dopamine-driven attention, amygdala amplification, hippocampal encoding, and prefrontal hypofrontality combine to create a self-transcendent awe that dissolves the boundary between self and planet. Behavioral studies confirm that this isn't fleeting sentiment—70% of astronauts report lasting increases in environmental commitment, and many have translated their experiences into activism, policy advocacy, and interdisciplinary research.

Yet the overview effect also raises critical questions. Who has access to this experience? How is the narrative shaped by political and cultural contexts? Can virtual simulations democratize the effect, or does it require the unmediated encounter with space? And can humanity cultivate a planetary perspective without waiting for mass space tourism?

The answers will shape the next chapter of human civilization. As climate change accelerates, biodiversity collapses, and geopolitical tensions mount, the need for a unified, long-term perspective has never been greater. The overview effect offers a glimpse of that perspective—but it's up to us to translate it into action.

Whether through virtual reality, education, art, or simply spending time in nature, we can begin to see Earth as astronauts do: a singular, irreplaceable oasis in the void. As Ron Garan urged, we must shift from "economy, society, planet" to "planet, society, economy." The overview effect shows us what's at stake. Now we must decide whether we'll act on what we've seen.

Over 80% of nearby white dwarfs show chemical fingerprints of destroyed planets in their atmospheres—cosmic crime scenes where astronomers perform planetary autopsies using spectroscopy. JWST recently discovered 12 debris disks with unprecedented diversity, from glassy silica dust to hidden planetary graveyards invisible to previous surveys. These stellar remnants offer the only direct measurement of exoplanet interiors, revealing Earth-like rocky worlds, Mercury-like metal-rich cores, and ev...

Hidden mold in homes releases invisible mycotoxins—toxic chemicals that persist long after mold removal, triggering chronic fatigue, brain fog, immune dysfunction, and neurological damage. Up to 50% of buildings harbor mold, yet most mycotoxin exposure goes undetected. Cutting-edge airborne testing, professional remediation, and medical detox protocols can reveal and reverse this silent epidemic, empowering individuals to reclaim their health.

Data centers consumed 415 terawatt-hours of electricity in 2024 and will nearly double that by 2030, driven by AI's insatiable energy appetite. Despite tech giants' renewable pledges, actual emissions are up to 662% higher than reported due to accounting loopholes. A digital pollution tax—similar to Europe's carbon border tariff—could finally force the industry to invest in efficiency technologies like liquid cooling, waste heat recovery, and time-matched renewable power, transforming volunta...

Transactive memory is the invisible system that makes couples, teams, and families smarter together than apart. Psychologist Daniel Wegner discovered in 1985 that our brains delegate knowledge to trusted partners, creating shared memory networks that reduce cognitive load by up to 40%. But these systems are fragile—breaking down when members leave, technology overwhelms, or communication fails. As AI and remote work reshape collaboration, understanding how to intentionally build and maintain ...

Mass coral spawning synchronization is one of nature's most precisely timed events, but climate change threatens to disrupt it. Scientists are responding with selective breeding, controlled laboratory spawning, and automated monitoring to preserve reef ecosystems.

Your smartphone isn't just a tool—it's part of your mind. The extended mind thesis argues that cognition extends beyond your skull into devices, AI assistants, and wearables that store, process, and predict your thoughts. While 79% of Americans now depend on digital devices for memory, this isn't amnesia—it's cognitive evolution. The challenge is designing tools that enhance thinking without hijacking attention or eroding autonomy. From brain-computer interfaces to AI tutors, the future of co...

Transformers revolutionized AI by replacing sequential processing with parallel attention mechanisms. This breakthrough enabled models like GPT and BERT to understand context more deeply while training faster, fundamentally reshaping every domain from language to vision to multimodal AI.