Digital Pollution Tax: Can It Save Data Centers?

TL;DR: Every year, 640,000 tons of abandoned fishing gear—ghost gear—continues killing marine life for decades, causing 45% of harm to threatened marine mammals despite being only 10% of ocean plastic. But a technology revolution is underway: AI-powered sonar achieves 90% accuracy locating lost nets, drones map remote coastlines in days instead of weeks, and biodegradable nets that completely decompose are entering trials. Success stories from Massachusetts to Thailand prove removal works, yet 75% of fishing vessels remain unmonitored and current cleanup rates would take centuries to clear existing gear. The solution demands coordinated action—consumer choices supporting sustainable fisheries, policy mandating gear tracking with positive incentives, Indigenous-led initiatives combining traditional knowledge with satellite tech, and circular economy models turning recovered nets into valuable products. We possess the technology to solve this crisis; what remains is mobilizing the collective will to act before ocean ecosystems collapse under the weight of synthetic debris.

Every year, 640,000 tons of fishing nets, lines, and traps are abandoned in our oceans—equipment that continues killing for decades. A single ghost net can trap and drown hundreds of marine animals before it finally breaks apart into microplastics that poison the food chain. Scientists now estimate that ghost gear accounts for 10% of all ocean plastic, yet it causes 45% of documented harm to threatened marine mammals. This invisible menace is reshaping ocean ecosystems, devastating coastal economies, and forcing humanity to confront an uncomfortable truth: the tools we use to harvest the sea have become its most lethal predators.

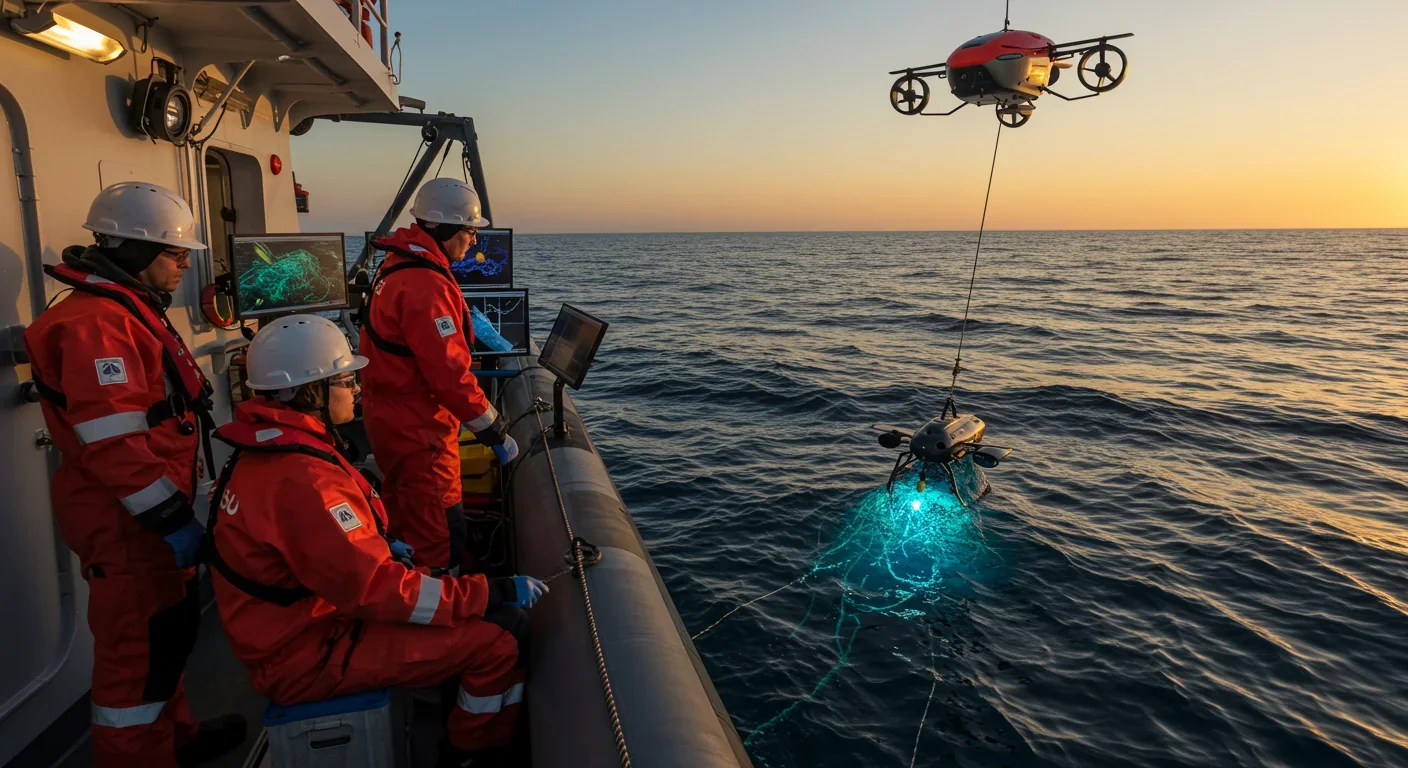

But a technological revolution is underway. From AI-powered sonar that can pinpoint lost nets on the seafloor to Indigenous-led drone mapping projects and biodegradable fishing gear that disappears harmlessly, innovators worldwide are waging war on ghost gear. The question is no longer whether we can clean our oceans—it's whether we'll act fast enough.

Ghost gear exists in a paradox: ubiquitous yet invisible, deadly yet ignored. Modern fishing nets are engineered from synthetic nylon that resists degradation for centuries, meaning a net lost today could still be trapping animals in 2250. These nets don't passively drift—they actively hunt, their mesh openings sized perfectly to ensnare fish, turtles, dolphins, and whales.

Until recently, finding ghost gear was like searching for needles in a haystack the size of continents. Traditional helicopter surveys cost tens of thousands of dollars per mission and could operate only in perfect weather. Divers could inspect perhaps a few hundred meters of seafloor per day. The scale of the problem—an estimated 48 million tons of lost fishing gear globally—made comprehensive cleanup seem impossible.

Then technology caught up with the crisis.

In 2024, researchers at Charles Darwin University deployed a game-changing system along Australia's Northern Territory coastline: drones equipped with AI-powered image analysis. Over 83.74 kilometers of remote coastline, they detected 72 ghost nets ranging from 50-centimeter fragments to intact five-meter nets partially buried in sand. What once required expensive helicopters and weeks of effort now takes days and costs a fraction as much. The drones capture high-resolution imagery with GPS coordinates precise to within meters, allowing Indigenous Anindilyakwa Rangers to plan efficient extraction missions using their purpose-built vessel Jarrangwa.

But aerial detection is only the beginning. Beneath the waves, scientists are deploying autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) equipped with side-scan sonar operating above 500 kHz—frequencies high enough to distinguish rope from rock, netting from natural reef structure. During a 2024 expedition in Swedish waters, WWF researchers used an AUV that covered nearly twice the area of traditional towed sonar systems, identifying abandoned fishing gear in Baltic harbour porpoise critical habitat.

The real breakthrough came when researchers combined sonar imagery with artificial intelligence. A platform developed by WWF Germany, Microsoft's AI for Good Lab, and Accenture achieved 90% accuracy in distinguishing ghost gear from underwater cables and natural formations. Previously, human analysts spent weeks manually reviewing sonar data. Now, the GhostNetZero.AI platform processes existing sonar datasets in hours, identifying potential ghost gear hotspots that divers can then verify and remove.

"If we can specifically check existing image data from heavily fished marine zones, this is a real game-changer," explains Gabriele Dederer, project manager at WWF Germany. The platform doesn't just detect gear—it creates a prioritized removal map, directing limited cleanup resources to the most ecologically critical areas first.

Meanwhile, acoustic technology is solving the prevention problem. The NetTag transponder system allows fishers to relocate lost gear by sending an interrogation signal that the tag answers from up to 2 kilometers away, pinpointing the location within five meters. Field trials in Portugal demonstrated that fishers could recover tagged gear in 10–15 minutes—transforming gear loss from permanent environmental damage to a minor operational hiccup.

For gear already lost, robotic retrieval is becoming viable. Deep Trekker's remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), starting at $6,000, can dive to ghost gear locations, photograph evidence, and use a grabber arm to secure nets for recovery—all operated by a single person from the surface. Unlike human divers who face decompression limits and cold-water hazards, ROVs can work continuously in conditions that would be lethal to people.

The most radical innovation may be prevention through design. The REMEDIES project is developing biodegradable fishing nets from polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) materials that maintain full fishing efficiency but completely break down in industrial composting facilities at end-of-life. Unlike conventional synthetic nets that persist for centuries, these nets could eliminate the ghost gear problem at its source.

Ghost gear's impact extends far beyond individual animal deaths—it's reshaping the economic foundations of coastal societies worldwide.

Consider the Chesapeake Bay, where over 145,000 lost crab pots kill approximately 3.3 million crabs annually. These aren't just numbers—they're lost income for watermen whose livelihoods depend on sustainable harvests. In British Columbia, a single crab fishery spends nearly $500,000 yearly replacing lost gear. Europe's fishing industry allocates €65.7 million annually—nearly 1% of total fishing revenue—to repair vessels and equipment damaged by marine debris, much of it ghost gear.

The economic damage multiplies through the ecosystem. Ghost fishing removes both target species and the forage fish that sustain commercial stocks. Some fisheries have experienced up to 30% stock declines attributed to ghost gear, creating a perverse cycle where fishers must work harder and deploy more gear to catch the same amount, increasing the likelihood of gear loss.

Tourism suffers too. Beach communities report revenue drops of up to 40% when ghost gear washes ashore, transforming pristine coastlines into garbage dumps. In the Florida Keys alone, scientists estimate over one million abandoned lobster and crab pots litter the seafloor, with 85,000 actively ghost fishing in the National Marine Sanctuary—a supposed protected area.

Yet the human toll goes deeper than dollars. Indigenous communities in northern Australia, Chile's Guaitecas archipelago, and the Pacific Northwest have maintained sustainable fishing traditions for millennia. Ghost gear from industrial fleets disrupts these practices, entangling traditional fishing grounds and forcing communities to choose between cultural heritage and physical safety. Benjamin Gonzales, a fisher in Chile, described how ghost nets create navigation hazards: "You never know when you'll hit one. It can destroy your propeller, strand you miles from help."

The cultural dimension matters profoundly. For Pacific Island nations, ocean health isn't just economic—it's existential. Ghost gear that degrades coral reefs destroys not just fish habitat but sacred spaces central to community identity. When reefs die, so does the intergenerational knowledge of navigation, sustainable harvest, and ocean stewardship that has sustained these societies.

Scientists are documenting ghost gear's role in accelerating ocean ecosystem collapse. Abandoned nets don't just trap animals—they physically damage coral structures, smother seagrass beds, and block sunlight critical for photosynthesis. As nets degrade, they release microplastics that accumulate in sediments and water columns. A 2024 study near Zakynthos, Greece, found microplastics from ghost nets in 99% of water and sediment samples, with particles entering the base of the food web.

The social implications grow more complex as climate change intensifies. Warming oceans are forcing fish stocks to migrate, creating new fishing grounds where regulations haven't yet been established. The resulting regulatory gaps increase illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing—practices strongly correlated with gear abandonment. When fishers operate outside legal frameworks, they have no incentive to report or recover lost gear.

Amid the crisis, extraordinary success stories demonstrate what's possible when technology meets determination.

In Massachusetts, the Center for Coastal Studies' Marine Debris Program concluded its 2025 season having recovered 520 lost lobster traps and removed 10,000 pounds of commercial fishing line. Using side-scan sonar to map hotspots and grappling equipment to retrieve gear, their six-vessel fleet worked with nine fishermen across multiple ports. "Without the support of the fishing industry and the port towns they fish out of, none of these cleanup efforts would be possible," noted Fritz McGirr, Marine Debris Operations Assistant. Crucially, 120 traps were returned to their owners—transforming a cleanup operation into an economic recovery program that builds industry support.

The Ocean Cleanup project has removed over 30 million kilograms of trash from rivers and the Great Pacific Garbage Patch since 2019, including significant ghost gear. Their System 03, a 2.25-kilometer floating barrier, uses 15mm mesh retention zones that allow most marine life to escape while capturing debris. In 2023, their Interceptor Barricade removed 10 million kilograms of trash from a single river in its first year—preventing ghost gear from ever reaching the ocean.

In Thailand's Gulf and Andaman Sea, a citizen science initiative trained recreational divers to survey ghost gear using simplified protocols. Across 100 dive sites, they documented 606 pieces of abandoned equipment totaling 1,200 square meters of netting. The discovery shocked policymakers: ghost gear is ubiquitous even in supposed protected waters. Though only 1% of recovered gear was clean enough for recycling (the rest too encrusted with marine growth), the Net Free Seas program has recycled 130 metric tons into products like electronic components and vehicle parts.

The Olive Ridley Project demonstrates the power of integrating removal, education, and economic incentives. Since 2013, they've removed 14.3 tonnes of ghost gear while recording over 1,000 sea turtle entanglements, rescuing and rehabilitating more than 250 injured turtles. Their work goes beyond cleanup—they partner with local communities to create alternative livelihoods that reduce fishing pressure while building stewardship.

Perhaps most inspiring are Indigenous-led initiatives. The Carpentaria Ghost Nets Programme trains Indigenous Rangers in northern Australia to use drones, sonar, and recovery vessels. Rangers completed nationally accredited Certificate III remote pilot training, building technical capacity on Country that ensures long-term program sustainability. Louise Mountford, one ranger, reflected: "I wasn't very comfortable doing it [flying drones], but I had the right people around me to overcome that and I'm very grateful." This isn't just environmental cleanup—it's technological sovereignty and cultural preservation.

In Greece, the Coasts Untangled project combines drone surveys with scuba-diving transects. In October 2022, divers retrieved the first ghost net—a 10-meter gill net—using coordinates from drone imagery. The methodology is now being replicated across 17 Mediterranean sites. Recovered nylon nets are sent to Healthy Seas, which works with the ECONYL regeneration program to transform abandoned gear into yarn used for socks, swimwear, carpets, and other products. In 2024, Healthy Seas removed the wreckage of an entire abandoned fish farm off Ithaca, though significant debris remains underwater.

Global policy frameworks are strengthening too. The Global Ghost Gear Initiative (GGGI) now includes 18 member governments and over 120 organizations, operating as a clearinghouse for removal strategies and best practices. Their Ghost Gear Reporter app allows anyone worldwide to document found gear with photographs and GPS coordinates, creating a crowdsourced database that guides recovery operations.

Despite progress, formidable barriers remain.

The vastness of the problem dwarfs current removal capacity. Cleanup crews measure success in tons; the problem is measured in hundreds of thousands of tons. For every net removed, dozens more are lost. The Ocean Cleanup estimates that even at current removal rates, it would take centuries to clear existing ghost gear.

Detection remains the fundamental challenge. Nets camouflage against seafloor backgrounds. Currents carry them across international boundaries, making jurisdiction unclear. In remote areas—where Indigenous communities often lack resources—ghost gear accumulates unchecked. "High fuel costs and lack of roads hinder transport of nets for recycling," explains Benjamin Gonzales in Colombia. "We used to send the nets to Buenaventura for recycling, but fuel costs are too high."

The economic barriers are equally daunting. A single ROV costs at least $6,000; professional sonar systems cost far more. Small-scale fishing communities can't afford such investments. Even well-funded programs face constraints: removing a single large ghost net can require 60 dives spanning weeks, as Conservation International discovered with a 90-meter, 2-ton net in Mexico's Espíritu Santo Archipelago National Park. The net had to be cut into sections, each lifted using inflatable bags, with marine life carefully relocated. "One wrong move could be fatal," noted diver Edgardo Ochoa.

Recycling challenges compound the problem. Nets recovered after years underwater are encrusted with barnacles, algae, and coral growth. Standard recycling machinery can't process them. Only about 1% of retrieved Thai ghost gear proved recyclable; the rest went to landfills, trading one pollution problem for another.

Policy gaps undermine progress. While Canada mandates that commercial fishers report lost gear via the Fishing Gear Reporting System, most countries lack equivalent requirements. Even where reporting exists, enforcement is spotty. About 75% of industrial fishing vessels don't appear in public monitoring systems, and AIS tracking data missed almost 90% of vessels detected by satellite radar in a 2024 study—suggesting that actual gear loss far exceeds reported figures.

International fragmentation stymies coordinated action. Ghost nets drift across exclusive economic zones, but each nation maintains separate regulations, monitoring systems, and enforcement priorities. A net lost in Indonesian waters might kill wildlife in Australian territory months later. The UN's International Maritime Organization recognizes ghost gear as a pressing concern, but binding international agreements with enforcement mechanisms remain elusive.

Bureaucratic inertia frustrates grassroots efforts. In Chile's Guaitecas archipelago, fish farm operators are technically required to remove debris within 10 days, with 95% compliance claimed by Chile's fisheries agency SERNAPESCA. Yet journalist investigations found abandoned infrastructure rotting in protected areas for years. "It's like having a guard dog with no teeth," fisher Daniel Caniullán told investigators.

Even successful removal faces unexpected challenges. When Healthy Seas divers cleaned an abandoned fish farm off Ithaca in 2021, they found Posidonia seagrass smothered beneath sunken net cages. Removal restored the site—but months later, new ghost gear had drifted back in. Without addressing the source of abandonment, cleanup becomes a Sisyphean task.

Perhaps most troubling, policy uncertainty threatens existing programs. In 2025, the U.S. administration proposed eliminating all funding for the Marine Mammal Commission, which coordinates responses to whale entanglements. "Entanglements are not decreasing, at least not in our region here on the East Coast," warns Scott Landry of the Marine Animal Entanglement Response Program. Heather Pettis of the New England Aquarium adds that entanglement impacts persist long after rescue: "Even in the absence of attached gear, entanglement events can impact growth, reproduction, feeding, ultimately survival down the road."

The ghost gear crisis reveals striking cultural differences in ocean stewardship.

Western approaches emphasize technological solutions and economic incentives. North American programs focus on gear tracking, buyback schemes, and recycling markets. The Florida net ban—passed by constitutional amendment in 1995 after a grassroots campaign collected 400,000 signatures—demonstrates the power of democratic environmental action. Post-ban monitoring showed only 4.8% of stranded sea turtles exhibited fishing-net entanglement, down from much higher pre-ban levels.

European nations lean toward regulatory frameworks and extended producer responsibility. The EU's Marine Strategy Framework Directive requires member states to achieve "good environmental status" in marine waters, with ghost gear reduction a key metric. Germany's net amnesty schemes allow fishers to dispose of old gear without penalty, while the recovered material feeds into circular economy channels. The approach recognizes that penalizing fishers for accidental loss discourages reporting and recovery.

Indigenous Pacific communities offer a radically different paradigm. Rather than viewing ghost gear as a technical problem requiring technological solutions, they see it as a symptom of broken relationships—with the ocean, with fishing traditions, with the concept of ownership itself. The Dhimurru Rangers' advocacy led to a $1.4 million Australian government commitment for regional ghost net action, demonstrating how Indigenous knowledge and political mobilization can shape national policy.

In Colombia, the grassroots organization Guardianes del Mar embodies community-driven conservation. Since 2017, volunteer divers have removed 700 kilograms of ghost gear from coastal waters, often working in dangerous conditions without government support. Diver Luis Antonio Lloreda describes using "intuitive interspecies communication" when freeing a humpback whale from netting: "I asked the mother for permission—energetically." Whether metaphysical or not, the approach reflects profound respect for marine life as subjects rather than resources.

Asian approaches vary dramatically. Japan and South Korea invest heavily in fishing technology with built-in tracking, viewing gear loss as inefficiency to be engineered away. By contrast, Southeast Asian nations with limited regulatory capacity rely more on NGO partnerships and international aid. Thailand's citizen science program succeeded precisely because it mobilized existing recreational diving communities rather than building new bureaucratic structures.

African coastal nations face unique challenges. Limited surveillance capacity makes IUU fishing—and associated gear dumping—endemic. Yet innovation emerges from constraint: satellite-based vessel tracking, pioneered in African waters, now provides a model for monitoring fishing activity in poorly regulated zones worldwide. Marine protected areas in African waters show nine times less fishing activity than unprotected zones when strictly enforced, demonstrating that clear boundaries work even with limited patrol resources.

The Mediterranean presents a laboratory for international cooperation and conflict. Greek waters host ghost gear from Turkish, Albanian, and Italian fleets. Removal initiatives like Healthy Seas and Ghost Diving operate across national boundaries, coordinating with local NGOs to navigate complex jurisdictional waters. Their success suggests that environmental crisis can transcend political divisions when stakeholders focus on shared ecological interests.

Perhaps most instructive is the contrast in how cultures value prevention versus cleanup. North Atlantic nations spend millions on removal programs but resist mandatory ropeless fishing gear that would prevent entanglements. Pacific Island nations, with far fewer resources, prioritize prevention through community-managed fishing areas where gear loss is socially sanctioned. The latter approach may be more sustainable—if we can scale the social mechanisms that make it work.

The ghost gear crisis demands action at every level—from individual choices to systemic transformation.

For individuals, the most powerful lever is consumer awareness. More than 90% of species caught in ghost gear are commercially valuable. Choosing seafood from fisheries certified by the Marine Stewardship Council (which now has stricter ghost gear requirements) or asking restaurant suppliers about their sourcing sends market signals up the supply chain. The Net Free Seas program demonstrates that consumer products made from recovered gear—ECONYL carpets, recycled netting turned into vehicle parts—can create economic incentives for proper disposal.

Citizen science opportunities abound. The GGGI Ghost Gear Reporter app allows anyone who finds abandoned gear to document and report it via smartphone. Recreational divers can join survey programs like Thailand's ghost gear mapping initiative. Coastal communities can organize beach cleanups that target fishing debris—the Coral Reef Alliance's patrols confiscated 11.3 kilometers of illegal nets in 2023 alone.

For fishing communities, adopting gear tracking technology is becoming economically rational. The NetTag acoustic system costs a fraction of typical gear replacement expenses. More broadly, participating in gear marking schemes and reporting lost equipment builds the data infrastructure needed for recovery programs. The Northwest Straits Foundation's success—5,800 nets and 8,000 crab pots removed—relied on fishers sharing locations of known debris.

For policymakers, the path forward requires three parallel tracks. First, mandate gear marking and reporting systems with positive incentives rather than punitive enforcement. Canada's no-fault Fishing Gear Reporting System models this approach. Second, invest in port reception facilities for end-of-life gear, closing the loop so fishers have somewhere to dispose of worn equipment responsibly. Third, support research into biodegradable gear alternatives—the REMEDIES biodegradable nets could eliminate the problem within a generation if widely adopted.

For technologists and entrepreneurs, opportunities abound. Current sonar-AI platforms achieve 90% accuracy; improving that to 95% would dramatically reduce false positives and wasted dive time. Developing lower-cost ROVs would democratize retrieval capacity. Creating markets for heavily fouled recovered gear—perhaps as construction aggregate or art installations—would solve the recycling bottleneck.

For educators, integrating ocean literacy into curricula can build the next generation of stewards. When students understand that ghost gear causes 45% of marine mammal entanglements despite being only 10% of ocean plastic, they grasp the outsized importance of fishing gear in ocean health. Service learning programs that connect schools with cleanup organizations turn abstract environmental problems into tangible action.

The skills needed for this work are diverse. We need more marine robotics engineers to refine AUV navigation in complex seafloor environments. We need GIS specialists to map ghost gear hotspots and prioritize removal. We need community organizers who can replicate the success of Florida's net ban campaign or the Dhimurru Rangers' advocacy. We need designers who can make biodegradable gear perform as well as synthetic alternatives. We need international lawyers to craft binding agreements that transcend national boundaries.

But perhaps most critically, we need systems thinkers who can see the connections. Ghost gear isn't just an environmental problem—it's an economic problem, a cultural problem, a governance problem, and a technological problem simultaneously. Solving it requires integrating prevention with removal, local action with international policy, high-tech solutions with traditional knowledge.

The encouraging news: every removed net immediately stops killing. Unlike climate change or ocean acidification, which require decades of mitigation before effects appear, ghost gear removal delivers instant results. Every recovered trap means crabs that will survive to breed. Every net pulled from a reef means coral polyps that can regenerate. The timescale of impact makes this a uniquely tractable environmental crisis—if we mobilize resources at scale.

We stand at an inflection point. For the first time in history, we possess the technology to locate ghost gear anywhere in the ocean, the robotics to retrieve it safely, the materials science to replace it with biodegradable alternatives, and the international frameworks to coordinate action across borders. The question is whether we'll deploy these capabilities before the crisis intensifies beyond recovery.

The next decade will be decisive. Current models predict that by 2035, ghost gear concentrations in some fisheries could reach levels that fundamentally alter ecosystem function—where the biomass of abandoned equipment exceeds the biomass of remaining fish. We're in a race between innovation and accumulation.

Yet there's reason for hope. The same fishing industry that created this problem is increasingly part of the solution. When fishers see their colleagues recovering gear worth thousands of dollars through tracking systems, economic self-interest aligns with conservation. When communities benefit from circular economy initiatives that turn trash into treasure, cleanup becomes sustainable. When Indigenous knowledge combines with satellite technology, we get solutions neither could achieve alone.

The ocean has always been humanity's blind spot—out of sight, out of mind. Ghost gear forces us to confront the consequences of that ignorance. Every piece of abandoned equipment tells a story about how we value convenience over consequence, about how we externalize costs onto ecosystems and future generations.

But every removed net tells a different story—one of redemption, ingenuity, and collective action. When a humpback whale swims free after Colombian divers spend hours carefully cutting away entangling lines, we glimpse what ocean stewardship can be. When Australian Rangers use drones to protect their ancestral waters, we see technology serving cultural continuity. When Greek citizen scientists create the data that changes national policy, we witness democracy functioning to protect the commons.

The ghost gear crisis is ultimately a mirror reflecting our relationship with the ocean. Will we continue treating it as an inexhaustible resource and invisible dumping ground? Or will we recognize it as a living system that sustains us—one that demands the same care we give to landscapes and communities we see every day?

The technology exists. The economic models work. The success stories prove what's possible. What remains is will—the collective choice to prioritize ocean health, to fund cleanup at scale, to transform fishing practices, to hold industries accountable, to honor the traditional knowledge of communities who've sustained themselves from the sea for millennia.

Six hundred forty thousand tons of ghost gear enter the ocean every year. That's a crisis. But it's also an opportunity—to demonstrate that humans can remediate the damage we've caused, that technology and tradition can work in concert, that economic and ecological interests can align.

The ocean's silent assassins are still out there, drifting through the depths, waiting for their next victim. But they're no longer invisible. We can see them now. We can find them. We can remove them. We can prevent new ones from being lost. The only question is whether we'll act before the opportunity passes.

The whales are waiting. The turtles are waiting. The fishers whose livelihoods depend on healthy oceans are waiting. The children who'll inherit what we leave behind are waiting. What will we tell them we did when we finally saw the truth? That we looked away? Or that we rolled up our sleeves and got to work?

The choice, as always, is ours.

Over 80% of nearby white dwarfs show chemical fingerprints of destroyed planets in their atmospheres—cosmic crime scenes where astronomers perform planetary autopsies using spectroscopy. JWST recently discovered 12 debris disks with unprecedented diversity, from glassy silica dust to hidden planetary graveyards invisible to previous surveys. These stellar remnants offer the only direct measurement of exoplanet interiors, revealing Earth-like rocky worlds, Mercury-like metal-rich cores, and ev...

Hidden mold in homes releases invisible mycotoxins—toxic chemicals that persist long after mold removal, triggering chronic fatigue, brain fog, immune dysfunction, and neurological damage. Up to 50% of buildings harbor mold, yet most mycotoxin exposure goes undetected. Cutting-edge airborne testing, professional remediation, and medical detox protocols can reveal and reverse this silent epidemic, empowering individuals to reclaim their health.

Data centers consumed 415 terawatt-hours of electricity in 2024 and will nearly double that by 2030, driven by AI's insatiable energy appetite. Despite tech giants' renewable pledges, actual emissions are up to 662% higher than reported due to accounting loopholes. A digital pollution tax—similar to Europe's carbon border tariff—could finally force the industry to invest in efficiency technologies like liquid cooling, waste heat recovery, and time-matched renewable power, transforming volunta...

Transactive memory is the invisible system that makes couples, teams, and families smarter together than apart. Psychologist Daniel Wegner discovered in 1985 that our brains delegate knowledge to trusted partners, creating shared memory networks that reduce cognitive load by up to 40%. But these systems are fragile—breaking down when members leave, technology overwhelms, or communication fails. As AI and remote work reshape collaboration, understanding how to intentionally build and maintain ...

Mass coral spawning synchronization is one of nature's most precisely timed events, but climate change threatens to disrupt it. Scientists are responding with selective breeding, controlled laboratory spawning, and automated monitoring to preserve reef ecosystems.

Your smartphone isn't just a tool—it's part of your mind. The extended mind thesis argues that cognition extends beyond your skull into devices, AI assistants, and wearables that store, process, and predict your thoughts. While 79% of Americans now depend on digital devices for memory, this isn't amnesia—it's cognitive evolution. The challenge is designing tools that enhance thinking without hijacking attention or eroding autonomy. From brain-computer interfaces to AI tutors, the future of co...

Transformers revolutionized AI by replacing sequential processing with parallel attention mechanisms. This breakthrough enabled models like GPT and BERT to understand context more deeply while training faster, fundamentally reshaping every domain from language to vision to multimodal AI.